Guerrilla Warfare in Civil War Louisiana

Guerrilla warfare in Civil War Louisiana attacked both Confederate and Union forces, as well as civilians.

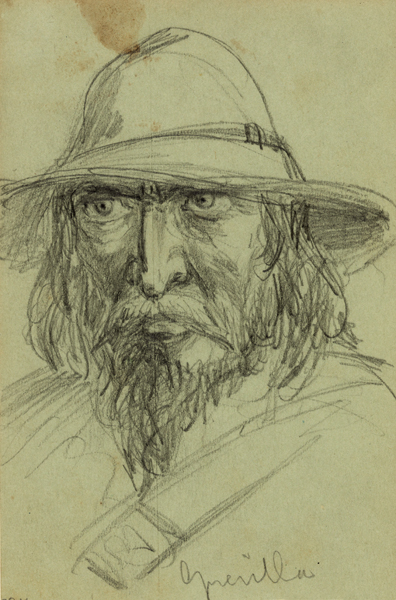

Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

"Guerilla" by Alfred R. Waud. Waud, Alfred R. (Artist)

The term “guerrilla” comes from the Spanish word for “little war,” which was used in reference to the small groups of armed citizens who used scorched-earth tactics against Napoleon during his invasion of Spain (1808–1813). While regular warfare, in which large field armies fought for control of strategic location and sought to overwhelm the enemy, was the main component of the American Civil War, irregular or guerrilla warfare was also evident, particularly in Louisiana.

Along with the occasional outraged citizen who vented his frustration personally upon the enemy, guerrilla operations served as the primary method of irregular warfare. Guerrilla warfare in Civil War Louisiana comprised small, mobile groups that conducted ambushes and raids against both Union and Confederate forces, and typically operated independently of any direction from regular army staff. Guerrilla bands frequently emerged as little more than outlaws who proved a scourge to the region in which they operated. In reference to guerrilla forces, Confederate General M. Jeff Thompson lamented, “instead of this arm of the service giving us the great advantages that it should, it became a terror to our own people and a disgrace to the true cavalryman or intelligent patriotic ranger.”

The overwhelming resources of the Union offered military advantages that became apparent during the course of the Civil War, and guerrillas, most notably in border regions such as Missouri, served as the most effective inhibitor of Union victory. As regular Confederate forces were driven from large regions of the South, guerrilla bands emerged as the only armed groups opposing the Federals. As early as the summer of 1862 Union forces had occupied significant portions of Louisiana and were launching destructive raids into the interior of the state. In response, emerging guerrilla units attacked Federal patrols, destroyed railroad tracks, and harassed suspected Union loyalists.

Through the course of the war guerrilla activity proved evident in virtually all regions of the state. In most cases the guerrillas inflicted minor damage, sometimes little more than theft, before quickly departing the region when regular Federal forces were dispatched to suppress them. In other areas, such as in northeast Louisiana around Lake Providence, guerrillas were employed to contain Federal spies and cotton speculators. In the late summer and fall of 1863, two companies of the notorious Missouri guerrilla commander William C. Quantrill’s force were deployed in northeast Louisiana. They effectively disrupted the spy and speculator network in the area until citizen complaints, which centered on the failure of guerrillas to respect private property in the region, led to their recall.

Following the fall of Port Hudson in the summer of 1863, guerrilla activity in the Florida Parishes increased dramatically as increasingly destructive Federal raids in the region ushered in a new level of misery, and the guerrillas responded in kind. In early 1864, Colonel John S. Scott assumed command of Confederate forces in the region. Although Scott did not sanction guerrilla operations, he made no effort to contain them. Through the close of the war guerrilla bands in the Florida Parishes proved increasingly effective. Though they offered little substantive protection to the residents, they did provide a mechanism for revenge.

Similar sustained patterns of guerrilla operations occurred along the lower Mississippi River near Donaldsonville, where the close proximity of nearly impenetrable swamps offered the guerrillas a safe haven from pursuit. In an effort to curtail guerrilla activity in the area, the Federal navy regularly shelled Donaldsonville and surrounding plantations, and the army launched probing raids into the interior of the river parishes to disrupt the guerrilla bases.

Guerrilla activity in the environs south of New Orleans and both north and south of Lafayette reduced Federal control almost exclusively to those urban centers and their military bases. By mid-1864 with Federal forces increasingly looting regional plantations and generally abusing the population—both black and white—guerrilla forces in the Lafourche district witnessed a dramatic increase in their numbers. Some of these new guerrillas were parolees from the surrendered Confederate garrisons at Vicksburg and Port Hudson, but most were younger men eager to have a crack at the Yankees. As in all areas of the state, the guerrilla operations offered little more than a bit of hope to the civilian population and sometimes created as many problems as they solved.

At the close of the war many of the men who engaged in guerrilla operations in Louisiana returned to peaceful pursuits. A few, especially some operating along the border region with Texas, became outlaws who contributed to continuing regional misery. Notably, many of the men who served as wartime guerrillas were now versed in the skills of extra legal violence and in how to apply those skills as a means to resolve grievances. Such lessons would serve as a painful legacy of guerrilla activities in post-war Louisiana.