H. L. Billiot v. Terrebonne Parish School Board et al.

In 1917 the Louisiana court system ruled that Native people occupied the same legal status as African Americans under Jim Crow.

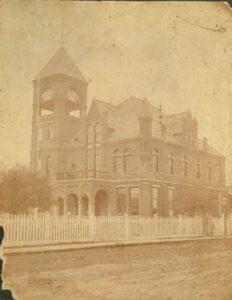

Randolph A. Bazet Collection, Archives and Special Collections, Nicholls State University, Thibodaux, Louisiana

The trial for H. L. Billiot v. Terrebonne Parish School Board took place at the Terrebonne Parish Courthouse in 1917.

Throughout Native American history, local, state, and federal government entities have generally determined tribal identity rather than Native communities themselves. In Louisiana H. L. Billiot v. Terrebonne Parish School Board et al. endures as an example of how the Houma Nation had their racial status determined for them by a court case. The trial had far-reaching implications not only for plaintiff H. L. Billiot and his family but for the entire tribe, as the judge ruled that they occupied the legal status of Black people.

Background and Legal Arguments

H. L. Billiot, the plaintiff, had attended public school in the 1890s below the Terrebonne Parish community of Montegut alongside both white and Native American people, which probably explained why he not only wrote with a strong and confident hand but also why he was comfortable in both communities. In 1916 he was thirty-two and residing with his family along Bayou Dularge in Terrebonne Parish. Given that his three sons Harry (twelve), Walter (ten), and Paul (eight) had progressed beyond the point where he could tutor them and that they were of mixed Native American and white ancestry, he gained permission from Terrebonne Parish School Board Superintendent H. L. Bourgeois for the boys to attend the nearby Falgout School, an all-white elementary school.

On September 13, 1916, Harry, Walter, and Paul reported for their first day of class and were told by a teacher that Bourgeois had rescinded his permission for them to attend. Billiot spoke with the teacher, then applied directly to Bourgeois, who told him that several parents had submitted a petition demanding that the mixed-race children not be allowed to enter the white school. Bourgeois told Billiot he could send his children to the school for Black children or withdraw them from the system, to which Billiot replied that, if the Terrebonne Parish School Board maintained its policy of racial segregation, then it was required to provide “separate but equal” facilities for all racial groups. His children were not Black but, that issue aside, the Black schools were inferior to the white ones. Billiot filed suit, and on February 3, 1917, H. L. Billiot v. Terrebonne Parish School Board et al. appeared in front of the 20th Judicial District in Houma.

The court record is a welter of languages, names, varying interpretations, documents from the colonial and federal periods, and recollections of events that transpired in the mid-1800s. Given the region’s legal and cultural conventions in 1917, arguments centered on whether the Houma plaintiff had any record of Black lineage, which would have excluded his children from white schools in Terrebonne Parish. Unable to prove its initial claim that H. L. Billiot had African ancestry, the school board changed tactics and focused on his wife, Celasie Frederick Billiot. Testimony hinged on her maternal grandfather, Etienne (“King”) Billiot Jr., and whether his paternal grandmother was Spanish and therefore legally white, as claimed in records, or whether she was of African ancestry. Thus, Harry, Paul, and Walter would enter Falgout School or be denied admission based on the racial or ethnic status of their great-great-great-grandmother.

Ruling

On March 26, 1917, the judge ruled for the Terrebonne Parish School Board. That both H. L. and Celasie Billiot were of mixed Native American and white ancestry was freely acknowledged throughout the trial. More importantly, while lawyers could not prove that King Billiot had African ancestry, they argued that he might have had African ancestry, an insurmountable barrier in the Jim Crow era. Billiot filed an appeal the same day, and in April 1918 the Louisiana Supreme Court ruled that damages did not meet the $2,000 minimum required for it to hear the case. The court based its decision on lost education and that each child’s schooling would have cost approximately $10 a month. For legal purposes, the Billiots were no longer members of the Houma Nation but were now classed as African American.

Significance

As part of the historical literature on Indigenous people in the Southeast, H. L. Billiot v. Terrebonne Parish School Board is not unique to the Houma Nation. On the contrary, the case fits squarely within a body of federal, state, and local decisions in which the dominant culture assigned racial and ethnic status to a tribe. However, Houmas view this case as very personal to them. First, it showed how a prominent tribal elder could be publicly humiliated when he went against the legal and social structures of Jim Crow Louisiana. H. L. Billiot was educated, a property owner, enjoyed the respect of Houma and non-Native communities, and supported his sons’ schooling. For those who wanted Indigenous people to gradually blend into the dominant culture, Billiot seemed to be the ultimate success story, but all his qualities counted for nothing. Moreover, the ruling devastated the rest of the tribe given its intricate and tightly woven kinship systems. The decision that Billiot’s children probably had African ancestry and were trying to pass themselves as Native American affected not only his immediate family but also the rest of the Houma Nation, effectively blocking them all from white schools. For their part, Houmas refused to attend Black schools, not because they disdained Black people but because to attend those schools would have meant relinquishing their Houma identity and seemingly giving credence to their oppressors’ determination. Though some private organizations stepped in to provide small schools that usually stopped at the sixth grade, Houmas in Terrebonne Parish did not gain access to high-quality public education until March 1963, after a ruling in Naquin v. Terrebonne Parish School Board.