Hubert Rolling

Hubert Rolling was a nineteenth century New Orleans pianist and composer.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

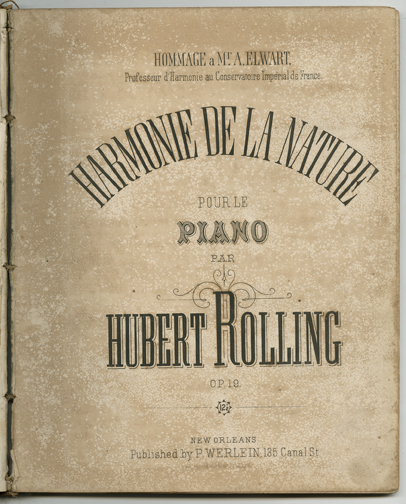

Harmonie de la Nature. Rolling, Herbert (Composer)

Among the pianist-composers who resided in New Orleans during the late nineteenth century, Hubert Rolling produced the most ambitious compositions. At the same time, he was able to compose accessible, quasi-patriotic marches that also pleased the general audiences of the city.

Born in the Alsace region of France in 1824, Rolling was educated in Strasbourg and at the Paris Conservatory; he moved to New Orleans with his parents in 1841. Although he became a full-time resident of New Orleans, he periodically returned to France. There he received many honors, published his music, and maintained close relationships with some of the leading musicians of the time. Rolling’s obituary in the New Orleans Daily Picayune referred to his lucrative career as an exceptionally accomplished teacher and stated that Rolling’s music was “severely classical in style and made few concessions to merely popular prejudices.”

“Marche Triomphale de l’Exposition des Amériques” (1885) is one of many pieces written for the 1884 World’s Industrial and Cotton Centennial Exposition in New Orleans and bears the dedication, “dédiée aux dames Louisianaises” (dedicated to the women of Louisiana). “Governor Francis T. Nicholls’s Triumphal March” (1877) and “Marche Triomphale: Hommage au General P. G. T. Beauregard” (1869) are military marches composed of simplistic thematic material. Rolling’s large-scale works are episodic compositions that attempt thematic transformation techniques akin to those applied by Franz Liszt in his orchestral tone poems. “Un Rêve des Concerts du Ciel” (1875) is an overtly religious work in which many of the sections are prefaced by inscriptions of Adrien Rouquette, a Louisiana-born Catholic priest, missionary to the Choctaw Indians, and poet. The piece depicts various states of religious fervor: a theme of love, an angelic song accompanied by celestial harps, a march of adoration, and a hymn of praise. Although “Un Rêve” contains some inventive writing, the overall effect of the piece falls short of its lofty inspiration due to the mundane nature of its themes and prevalent use of tremolo and arpeggio figurations.

Rolling’s two earlier large works are decidedly more successful. “Harmonie de la Nature” is a set of variations on a melodie pastorale and is rich in bucolic imagery: bagpipes, a storm, birdcalls, and peasant dances. In many episodes, the textures are multi-layered and imaginative, and the piano resonates through the acoustical use of the pedal. Rolling’s most profound work is “Appel à Dieu,” which bears the dedication, “à la memoire des victims de la guerre civile des Etats Unis” (dedicated to the victims of the United States Civil War). The piece is essentially an extended funeral march, its main theme reminiscent of the slow movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Eroica symphony. A striking feature of “Appel à Dieu” is the imitation of a carillon that opens the piece and returns at a pivotal point before the final “Hymne de la Glorification des Martyrs.” The conclusion of the work is open-ended and pessimistic, as the march seems to recede into memory.

Rolling died in New Orleans in 1898.