J. D. Miller’s Recording Studios

J. D. Miller’s recording studios in Crowley are best known for recording South Louisiana musical genres but the studio leaves a mixed legacy, having produced a series of racist songs in the 1960s.

Cajun and Creole Music Collection, Special Collections, Edith Garland Dupré Library, University of Louisiana at Lafayette.

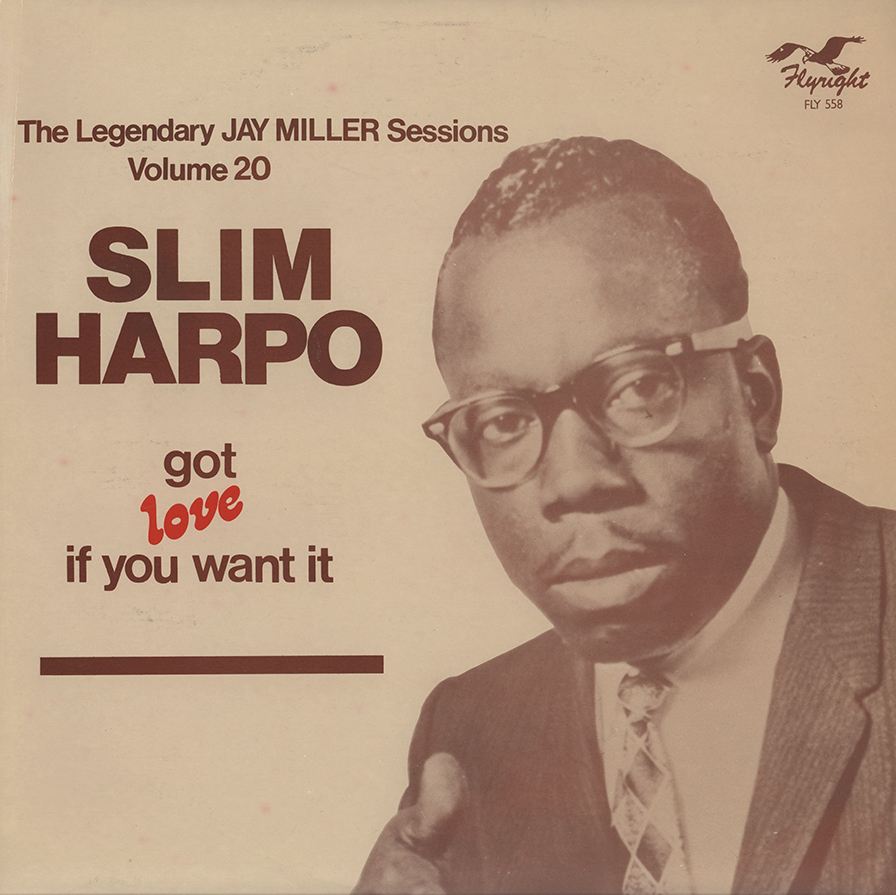

Slim Harpo's "Got Love If You Want It" album recorded by J. D. Miller, 1980.

J.D. Miller’s recording studios in Crowley, in Acadia Parish, have been the scene of both high and low moments in the history of Louisiana music. An accomplished and prolific producer, Miller applied his sonic expertise to the overlapping South Louisiana genres of Cajun music, zydeco, blues, rhythm and blues (R&B), swamp pop, country, and early rock and roll, with often excellent results and some national-level success. As Katie Webster, a respected blues/R&B pianist who played on many of his sessions, observed, “When you go into J. D. Miller’s studio you have to cut perfect records.” However, Miller is also reviled, in his role as a label owner, for releasing a series of racist songs in the 1960s that are still revered today by extremist devotees of the contemporary white supremacist genre known as “hate-core.” This facet of Miller’s work stands in stark and paradoxical contrast to his keen aptitude for producing high-quality records by Black artists.

Miller’s Musical Beginnings

Born in 1922 in Iota near the town of Crowley, James Denton Miller began playing guitar at age eleven. In 1933 he won a talent contest in Lake Charles for his rendition of Huey P. Long’s campaign song “Every Man A King.” For the next decade Miller played with seminal Cajun bandleaders including fiddlers Harry Choates and Leo Soileau and accordionist Amedée Breaux.

In 1946 Miller began recording Cajun music, initially using Cosimo Matassa’s studio in New Orleans before setting up a rudimentary facility in his house in Crowley in 1947. The mid-to-late ’40s saw a resurgence of the accordion in southwest Louisiana, following years of some disfavor during the Cajun string-band era. Miller tapped into this trend. His first label—Fais-Do-Do Records (soon to be renamed Feature Records)—released Cajun material by such accordionists as Aldus Roger, Austin Pitre, and Amedée Breaux, as well as the Cajun-country creations of guitarist and singer Jimmy C. Newman, and the Cajun/western swing sound of guitarist Happy Fats (born Leroy LeBlanc) and the fiddler Oren “Doc” Guidry.

Ventures and National Success

For the next two decades Miller released records under numerous, differently named labels, including Zynn, Kajun, Blues Unlimited, and MTE. Two notable musicians among the multitude he recorded included the preeminent zydeco accordionist Clifton Chenier and the hard-rocking Cajun accordionist Wayne Toups. During this time, as often occurs in the record business, disputes arose regarding songwriting credits and royalty payments. Certain artists claimed that they, rather than Miller, had written certain songs and thus owned such rights and were owed royalties.

In 1952 the country singer Kitty Wells recorded “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky-Tonk Angels,” for which Miller had written the lyrics. The song topped the national country charts, as tabulated by Billboard magazine. In 1953 Miller’s lyrics for “That’s Me Without You” earned a number-four spot for fellow Louisianan Webb Pierce. These hits significantly elevated Miller’s profile in the music industry and led to an important connection for him with the Nashville-based Excello Records.

In 1957 Miller began focusing on R&B, blues, zydeco, and what would later come to be called swamp pop by South Louisiana artists Carol Fran (born Carol Anthony), Lightnin’ Slim (born Otis Hicks), Silas Hogan, Warren Storm (born Warren Schexnider), Lazy Lester (born Leslie Johnson, and Slim Harpo (born James Moore). Because of the erratic cash flow that often plagues small record companies and can bankrupt them, Miller set up a deal to license some of his blues recordings to Excello to make and distribute records. Songs by Slim Harpo, Lightnin’ Slim, and others were said to typify “the Excello sound”—with its raw exuberance and uncluttered instrumentation—creating the mistaken impression that such music originated in Nashville rather than in South Louisiana.

Miller and Excello’s biggest hit was Slim Harpo’s “Baby Scratch My Back” in 1966. Despite its deeply regional rural sound, the song made an unlikely climb to number sixteen on the national pop charts. “Baby Scratch My Back” is one of the best examples of Miller’s masterful production. Moore’s understated singing and full-toned harmonica work floated above a dense rhythmic texture highlighted by deft, off-beat percussive accents played on wood blocks. The song also utilized the catchy “chicken scratch” guitar sound of James Johnson, which mimicked barnyard poultry.

Racist Records and MasterTrak Studio

In 1966 Miller released his first racist records, appearing on his Reb Rebel label and ascribed to a singer named Johnny Rebel. These songs included “Kajun Ku Klux Klan” and “N***** Hatin’ Me,” among other incendiary titles. Miller wrote some of them under the pseudonym Jerry West, a nom de plume that he also used on some blues and R&B hits. For decades music journalists rationalized this material as “political humor.” Recent writings have a much more critical tone, employing such descriptors as “…a hate crime in the form of a song.” Even so, many references to J. D. Miller still depict him in a purely positive light, as “a legend,” with no mention of the Johnny Reb records.

In 1967 Miller built the MasterTrak studio in Crowley. With ongoing equipment upgrades, MasterTrak was praised in the ’90s as “possibly the most technologically sophisticated studio in Louisiana.” Soon after its construction, though, Miller took a job with the town of Crowley and turned the business over to his sons. In 1985 John Fogerty, of the ’60s–’70s rock band Creedence Clearwater Revival, came to Crowley to record a rendition of the zydeco hit “Don’t Mess with My Toot-Toot” by Rockin’ Sidney (born Sidney Simien). Simien and his band accompanied Fogerty. The noted singer and songwriter Paul Simon also recorded a song at MasterTrak—“That Was Your Mother,” with zydeco accompaniment by Rockin’ Dopsie (born Alton Rubin)—for his 1986 album Graceland.

J. D. Miller passed away in 1996. As of October 2022 MasterTrak remains open for business.