Jim Crow and Segregation

After the Civil War, African Americans gained some political rights and power before having them taken away again during the era of Jim Crow laws and segregation.

This entry is 8th Grade level View Full Entry

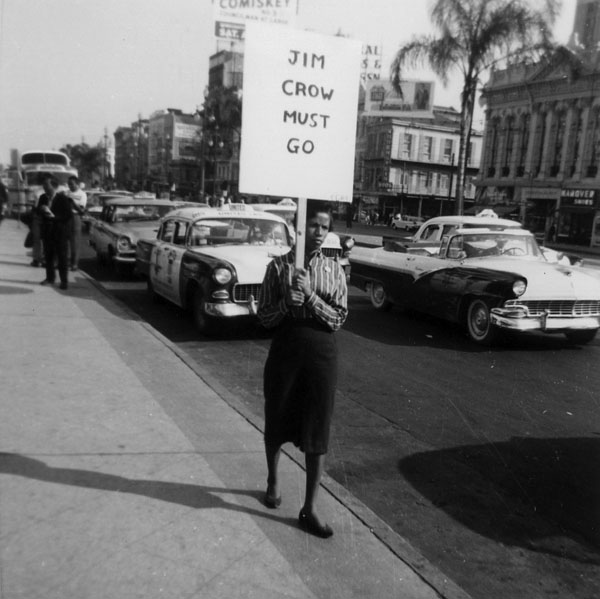

Courtesy of the Amistad Research Center at Tulane University.

A black and white reproduction of a photograph of a New Orleans CORE protest at Woolworths and McCrory's on Canal Street, April 1961.

How did rights for African Americans improve during Reconstruction?

During the Reconstruction period, from 1865 to 1877, African Americans gained some political rights and power. In 1865 the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery. Two years later the Fourteenth Amendment gave African Americans citizenship and equal protection under the law, and in 1870 the Fifteenth Amendment gave African American men the right to vote. In the five years after the Civil War, Louisiana’s Republican-controlled legislature, which included African American legislators for the first time, passed a new state constitution and civil rights legislation that gave political rights to African Americans. By 1875 almost four thousand schools for Black students were established. By that same time more than fifteen hundred African Americans had run for office as state and national representatives.

How were rights for African Americans undermined after Reconstruction?

At the end of Reconstruction in 1877, many white Louisianans tried to remove the gains African Americans had made. The Jim Crow system in the American South was a system of laws and rules that established racial segregation and unequal treatment of Black and white people. Post-Civil War racism, driven by lingering Confederate anger at losing the war and a desire to maintain a social and political hierarchy based on race, was a key feature in the formulation of Jim Crow laws. The term “Jim Crow” came from minstrel shows, which were popular music, song, and dance performances that traveled throughout the country in the mid-nineteenth century. In these shows the Black Jim Crow character was represented as a lazy fool who was meant to be laughed at. By 1880 “Jim Crow” was used to describe state and local laws that legalized mistreatment of Black people and segregation based on racist beliefs. Under this system Black people were treated as inferior to white people. More than eighty years would pass before civil rights workers were able to reverse these laws.

During Reconstruction the federal government gave some protections to African Americans. However, during this time the state legislature and parish governments began passing laws known as “black codes.” These laws restricted the lives of Black people in many ways. They determined the types of businesses African Americans could own and the time of day they could visit downtown. The codes stopped more than three African Americans from gathering in one place. They also gave white people legal power over Black people when no police officer was present. Though black codes were found in every parish, they were most strongly enforced in Louisiana’s northern and eastern parishes. In South Louisiana, African Americans were allowed much more freedom. South Louisiana, and especially New Orleans, was more racially diverse than the other parts of Louisiana. Free people of color (people of African ancestry who were free before the end of slavery) in New Orleans often had a mixed racial heritage and enjoyed more freedom in their businesses and social interactions than in other parts of the state. At the beginning of Reconstruction, Louisiana sent several Black politicians to the US House of Representatives. P. B. S. Pinchback, an African American, served as governor of Louisiana from late 1872 to January 1873. By the time federal protection for African Americans ended in 1877, African American politicians were no longer in power.

By 1890 the Democratic Party planned to completely remove the Republican Party by disenfranchising, or preventing voting access to, Black people. Because Southern Black people strongly supported the Republican Party, white Democrat leaders used poll taxes, literacy tests, residency requirements, and “understanding” clauses to prevent Black people from voting. Poll taxes were fees that had to be paid before a person could register to vote. Local voting officials administered literacy tests to African Americans and designed questions that set them up to fail. Examples of questions found on literacy tests include: How many bubbles are in a bar of soap? How many jellybeans are in this jar? What are the first twenty articles of the US Constitution? Despite the rights guaranteed to African Americans by the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, they were excluded from the political process. Social segregation soon followed.

The Louisiana legislature passed a law that officially segregated railroads in the state in 1891. In 1892 Homer Plessy bought a first-class ticket on a New Orleans train and attempted to sit next to white passengers. Plessy was a member of a New Orleans civil rights organization, the Comité de Citoyens. He was arrested for breaking the law and sued the railroad company. Plessy’s lawyers argued that segregation denied him equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Plessy lost the case in the US Supreme Court. In the Plessy v. Ferguson court case, the Supreme Court upheld the Louisiana law. Speaking for the majority, Justice Henry Brown stated that segregation did not deprive Plessy of his rights. Since a majority of Supreme Court justices agreed that Black people and white people were physically unequal, it ruled that racial segregation was also allowed, as long as the law tried occasionally to treat them equally. The 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case established the “separate but equal” doctrine, which allowed for legal segregation as long as facilities for Black people were equal to those reserved for white people. However, in almost all public places—schools, hospitals, trains, restaurants, hotels, parks, cemeteries, the military—white people were treated better than African Americans. After the decision some institutions excluded African Americans completely.

Two years after the Plessy decision, in 1898, Louisiana passed one of the first laws officially removing the right to register to vote from Black people. It also passed a new state constitution, which further restricted the rights of African Americans. Everything that could be segregated in Louisiana was. Public places, including restaurants, hotels, night clubs, cemeteries, amusement parks, playgrounds, and schools were all segregated.

By 1900 segregation was fixed in Louisiana’s culture. New Orleans streetcars were segregated after 1902. A 1908 state law prohibited marriage between white and Black people, and jails became legally segregated in 1920. Even in New Orleans, tolerant interactions between whites and African Americans disappeared. The Catholic Church established a segregated parish in downtown New Orleans, the Congregation of Corpus Christi.

Lynchings—killings for an alleged offence without a legal trial—increased greatly after 1900 and were especially common in the North Louisiana parishes of Caddo, Ouachita, and Morehouse. Across the South, the numbers of African Americans lynched between 1865 and 1965 are in the thousands. However, the numbers of lynchings that took place is hard to determine. Police officers in the northern parishes rarely considered lynchings as murders. Lynchings and the threat of lynching made many African Americans afraid of rebelling against Jim Crow.

The impact of segregation and the legacies of systemic racism in areas like housing, employment discrimination, wealth and income inequality, and healthcare continue to impact Louisiana’s culture and history today.