John Scott

John T. Scott, raised in New Orleans's Ninth Ward, is best known for his vibrantly colored kinetic art.

Courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

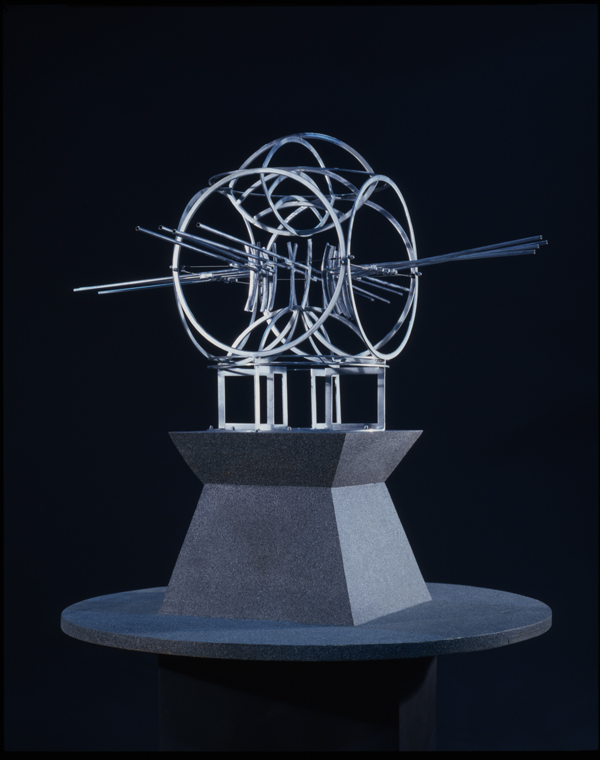

Galileo. Scott, John(artist)

Winner of a prestigious “genius grant” from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation in 1992 at the apex of his career, artist John Scott was born in New Orleans and raised in the city’s Lower Ninth Ward. He taught at Xavier University for more than forty years and was known for creating vibrant kinetic sculptures that often explored themes such as the “diddlie-bow” string instrument from West African culture, or the rhythms and movements inspired by early nineteenth-century slave dances in the New Orleans’s famed Congo Square. His large woodcuts drew heavily upon life in city, especially its rich African-Caribbean culture and musical heritage. John Scott was praised as “a New Orleans sculptor whose vibrantly colored kinetic art filtered the spirit of the African diaspora through a modernist lens,” according to his obituary in the New York Times (September 4, 2007).

Scott was born June 30, 1940, to Thomas Scott and Mary Mable Scott on a farm in the Gentilly section of New Orleans and raised in the city’s Ninth Ward. He attended Xavier University, a Roman Catholic and historically black college, and then Michigan State University where he studied with the painter Charles Pollock, Jackson Pollock’s brother. After completing his master of fine arts degree in 1965, he returned to Xavier to teach, and he remained on the faculty until his death. His artworks drew heavily upon life in his hometown, especially its rich African-Caribbean culture and musical heritage. His sculptures explored themes such as the diddlie-bow string instrument from West African tradition, or the rhythms and movements inspired by early nineteenth-century slave dances in New Orleans’ famed Congo Square. Other works captured the iconic symbolism of his Roman Catholic upbringing, such as in his 1970 steel assemblage titled Crucifixion, or the harshness and brutality of poverty, as seen in his series Third World Banquet (1998), which showed bronze dinner plates filled only with spikes. His large woodblock prints featured jazz funerals, second line parades, and Louis Armstrong, among other New Orleans subjects.

Scott knew early in life that he would be an artist. A teacher at Booker T. Washington High School in New Orleans urged him to attend Xavier. It was there he came under the influence of Numa Roussève and Sister Mary Lurana Neely, two members of the university’s progressive art faculty who later encouraged him to teach at his alma mater. A few months after being hired at Xavier, Scott married his longtime girlfriend Anna Rita Smith in 1966. The couple had five children.

A milestone in his career came in the summer of 1983, when Scott received a grant to study in New York under the internationally acclaimed sculptor George Rickey. Prior to this six-week residency, Scott had been interested in doing kinetic sculpture but didn’t want to mimic Rickey or the work of famed mobile sculptor Alexander Calder. Scott’s apprehension was relieved when Rickey advised, “Don’t sweat it, just do your work.”

Scott’s breakthrough as a kinetic sculptor came when he constructed his Diddlie Bow series in the early 1980s. His inspiration came while he was working on an exhibition titled I’ve Known Rivers for the African American pavilion of New Orleans’ 1984 Louisiana World Exposition. In his research for the commission, Scott came upon a West African tale about the diddlie bow, which he related to Jacqueline Bishop in a 2002 public radio interview. “When the early hunters killed something it was a tremendous sense of remorse,” he said. “So, the hunter would turn his bow over, change the tension on the string, and have a companion play the string. That would give a libation of sound to the soul of the animal that gave its flesh to the people. That idea so struck me that I started making bow-shaped sculptures. It dawned on me almost immediately that [if I had] any line between two points and I stuck something on that line I had a kinetic vocabulary.”

Scott continued, “The ritual of using a weapon of war to create a libation of spiritual peace is commonplace. Wherever [Africans] went in the diaspora, the instrument came with us. That instrument came into the Mississippi Delta and it was called the diddlie bow. The musician’s name Bo Diddley came from that instrument.”

The MacArthur Foundation grant enabled Scott to secure a larger studio to undertake large projects in the 1990s, such as Spiritgates (1994), commissioned for the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA). A 2005 exhibition catalog described Spiritgates as a “sculptural masterpiece with intricate shapes and spaces dancing atop an elegant frame, the artwork serves another role as an entryway into the Museum. Spiritgates uses Scott’s unique visual language to change a stationary installation into a kinetic sculpture where ‘the people provide the movement as they walk by.’” The grant also launched the most productive period of his career. In 2005, NOMA recognized his contribution to American art in a major retrospective, Circle Dance: The Art of John T. Scott. A month after the show closed, Hurricane Katrina devastated the city, forcing Scott to flee to Houston.

Ironically, Scott, with perhaps some unknowing premonition, executed a series of black-and-white woodcut prints in 2002 and 2003 with imagery of New Orleans that could have been done immediately after the hurricane on August 29, 2005. In works such as Cathedral (2006) and Storm Coming (2006), mass destruction of the city is depicted, with damaged houses, cars, and other flotsam of life piled high in mountains of debris.

In the catalog that accompanied his 2005 retrospective at NOMA, Scott used the words “jazz thinking” to described his mind-set while creating his art: “[I]f you listen to a really good jazz group three things are always evident. . . [The] jazz musicians are always in the ‘now’ while you’re hearing it, but these guys are incredibly aware of where they have been and have an unbelievable anticipation of where they are going.”

Scott constantly looked to the soul and passion of New Orleans and Delta music to inform his work. “I think my sculpture is a lot like the blues and jazz,” he said to Bishop, who asked him during a radio interview if he thought his work was narrative. “If one looks at the blues, the blues is a narrative. It’s a story. Jazz just elevates the blues leaving the storyline out and just taking the structure. I think my work can be taken on many levels. It is narrative in nature but the narrative is very abstract. There are other times when there’s nothing more than the rhythm, the color and the structure.”

Like many New Orleanians living in exile after Hurricane Katrina, Scott looked forward to returning home. Two months before he died, New Orleans Times-Picayune art critic Doug MacCash interviewed Scott by telephone in Houston. “That’s the only home I know. I want my bones to be buried there. I belong there. I need New Orleans more than New Orleans needs me.”

In describing the constant influence of New Orleans culture and music upon on his work, Scott said, “New Orleans is the only city that I’ve been in that if you listen, the sidewalks will speak to you.” He reflected upon those sounds: “To me, New Orleans is like Dracula’s casket. I can travel anywhere but I have to be here to be alive because a lot of my ideas are coming out of the culture of this city, coming out of the reality of this city.” Elaborating on what he meant by the city’s special culture, he said, “Other people talk about culture, but I think people here live their culture. When you see people dancing in the street, it’s not about entertaining somebody. It’s not about art, it’s about life.”

The single largest public collection of John Scott’s major work is permanently displayed at The Helis Foundation John Scott Center of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities. Scott’s work is also included in the collections of the New Orleans Museum of Art, the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, the Louisiana State University Museum of Art in the Shaw Center for the Arts in Baton Rouge, the Amistad Research Center Collection in New Orleans, the Blanche and Norman C. Francis Collection at Xavier University of Louisiana in New Orleans, Loyola University of New Orleans, the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, Texas, the Scripps Collection in Claremont, California. the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia, and Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee.

On September 1, 2007, Scott died in Houston, where he had evacuated in 2005, after two double lung transplants and a long struggle with pulmonary fibrosis. He was sixty-seven.