Kendall Shaw

For six decades, Kendall Shaw's art literally and metaphorically has incorporated complex layers of history, reflecting extended passages of time, his process, life experiences, and the changing styles and directions of the American art world.

Courtesy of Ogden Museum of Southern Art

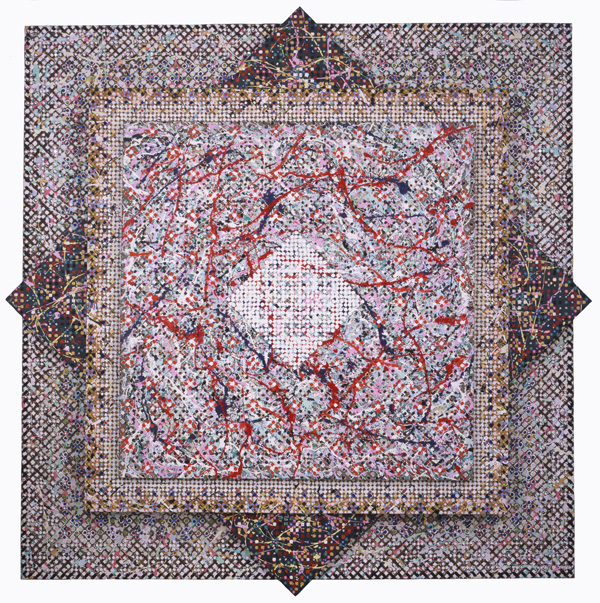

Sunship (for John Coltrane). Shaw, Kendall (Artist)

For six decades, Kendall Shaw’s art has literally and metaphorically incorporated complex layers of history, reflecting extended passages of time, his painterly processes, his life experiences, and the changing styles and directions of the American art world. His greatest national and international recognition came with the appearance of the Pattern and Decoration movement in painting (also known as the New Decorativeness), beginning in the mid-1970s, advanced by Shaw and artists including Joyce Kozloff, Valerie Jaudon, Mimi Schapiro, and Robert Kushner. Shaw combined his interests in mathematical patterns and systems, New Orleans music and rhythms, and a growing interest in Peruvian textiles and Navajo weaving patterns to create his distinctive pattern and decoration paintings. He also created patterned works in tribute to his grandmother Emma Lottie by making abstract paintings that were grounded in his New Orleans family and experiences.

A New Orleans native, Shaw first painted at Louisiana State University under the guidance of O. Louis Guglielmi from 1950 to 1951, then with Guglielmi and Stuart Davis from 1951 to 1952, followed by Ralston Crawford in 1953 in New York City. Shaw returned to New Orleans to earn a master of fine arts degree in painting at Tulane University, working with Ida Kohlmeyer, George Rickey, Kurt Krantz, and Mark Rothko. Encouraged by Rothko to return to New York City, Shaw did so. Since 1961 he has been a successful artist and teacher there, working first in a SoHo studio, and then a Brooklyn brownstone, creating works in styles ranging from Abstract Expressionism, to Pop Art, to Minimalism, to Pattern and Decoration painting, and beyond. Through these years his roots in New Orleans have influenced his art, as critic Marticia Sawin has suggested:

“Anyone who has ever decked themselves in garish beads tossed from a Mardi Gras float will recognize the vestigial New Orleanian in Shaw who was reared in the heady mix of the city where some of the liveliest and most triumphant music was played at funeral processions.”

Shaw was born in New Orleans in 1924, and raised there. He recalls that his father, George Kendall Shaw Sr., was a gifted stride and ragtime piano player, and that jazz music has always been an essential part of his life and art. One of his greatest inspirations was his paternal grandmother, Emma Lottie, who was a unique New Orleans character. A founder of the city’s ERA Club, she was a suffragette and a social progressive who advocated for women’s right to vote and for the elimination of child labor in New Orleans, as well as for improvements in education and community health care. She always dressed properly in linen, chiffon, jewels, and feathers, materials that Shaw reflected in the art forms he created in her memory, including Emma Lottie Marches for the Right to Vote (1979) and Emma Lottie’s Scandalous Divorce (1979).

Growing up, Shaw did not plan to become an artist. After he enlisted in the Navy during World War II, he studied chemical engineering and physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta in an officer’s training program. After the war, he enrolled at Tulane University in 1947 and completed a BS degree in chemistry in 1949. However, when he attended Louisiana State University to study chemical engineering in 1950, he became friends with another New Orleans native, George Dureau, who encouraged Shaw to paint with Guglielmi. Shaw had a promising future in industry, working with the Stauffer Chemical Company, yet he became devoted to painting. “Painting had become my key to reality, but science remained in my perception of reality,” he said. After living in New York, he returned New Orleans to work and live, and then he was offered a teaching assistantship with Kohlmeyer at Tulane.

Working with Kohlmeyer and Rothko in New Orleans, Shaw became increasingly fascinated by abstract art and Abstract Expressionism, exploring the possibilities of abstract painting while he completed his graduate studies at Tulane from 1957 to 1959, earning his master of fine arts degree in 1959. He completed an important early abstract painting, Northside Light, in 1961, the year he accepted a teaching position at the Columbia School of Architecture, taking him back to New York City, where he has remained to the present date. In 1964 he joined the Tibor de Nagy Gallery, and in 1966 he became a member of the Hunter College Art Department faculty, where he taught from 1966 to 1970. He later taught at the Brooklyn Museum Art School from 1970 to 1977, the Parsons School of Design from 1966 to 1986, and the Fashion Institute of Technology from 1984 to 1986.

As the New York art world evolved in the following decades, so did Shaw’s art. He began to paint sports figures based upon newspaper photographs, reflecting subjects associated with Pop Art, as evident in Stichweh Tackled (1963), and then developed works that reflected the movement to Minimalism, including Sainte Chapelle (1968) and Apollo (1969).

A major painting in this evolving direction was titled Sunship (1982), composed of multiple, stacked and painted canvases, designed in tribute to John Coltrane’s jazz, specifically his recording, Sunship. During the following years, Shaw continued to explore a number of these aesthetic issues in his paintings, while he also continued his teaching activities, and exhibited in numerous gallery and museum exhibitions in America and Europe. Major health concerns dominated his life for more than a decade in this period, yet he continued his painting and teaching activities. As the twenty-first century unfolded, Shaw decided to revisit and rework many earlier canvases, incorporating a new interest in Old Testament themes, leading to the series Let There Be Light, evident in works such as the series namesake, Let There Be Light, completed over a twenty-year period, (1984-2005),The Blessing of Abraham After the Sacrifice (1988-2005), and The Great Flood (1981-2005), reflecting both his biblical interests and the impact of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans.

The Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans in 2007 organized a major survey exhibition of Shaw’s paintings, with a focus on the Let There Be Light series. Shaw’s works then traveled to England as the Ogden’s first international touring exhibition, where it was presented at the Ruskin Gallery at the Cambridge School of Art. Shaw’s Pattern and Decoration paintings had a significant influence on contemporary English painters, and the show was regarded as an important exhibition in that country. Shaw has continued to paint and advance this series in New York, with exhibitions there in 2010 and 2011. His art is included in numerous museum collections, including the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art, Tulane University Museum Collections, the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson, and the Brooklyn Museum in New York.