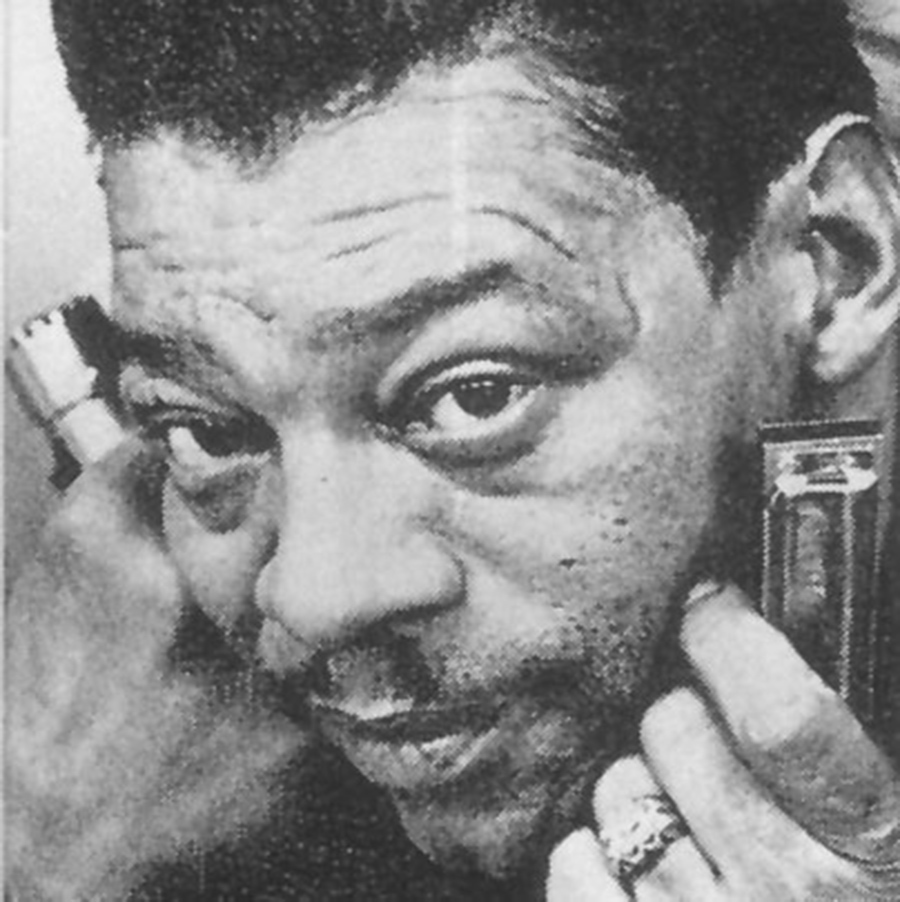

Little Walter

Louisiana blues harmonica musician Little Walter Jacobs had his biggest hit with "Juke" in 1952.

Wikimedia Commons

Little Walter.

Considered by many to be the greatest blues harmonica player ever, Marion “Little Walter” Jacobs rose from obscurity in Marksville to international acclaim in the blues scene of Chicago. During the first half of the 1950s he became one of the key architects of the electrified Chicago blues style, an ensemble, collaborative, urban approach that became the defining sound of both electric blues and blues-based rock throughout the remainder of the twentieth century and beyond. He also was an accomplished blues singer and songwriter, but his induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2008 was based largely on his work as a sideman for blues guitarist Muddy Waters.

Born on May 1, 1930, Jacobs was abandoned by his mother at birth and raised by his father’s family on a farm outside Alexandria. He began playing harmonica at the age of eight, learning polkas and waltzes. He left home at an early age and was playing on the streets of New Orleans by the time he was twelve, modeling his primitive blues style on the music of John Lee “Sonny Boy” Williamson. Two years later Jacobs made his way to Helena, Arkansas, where he furthered his education in traditional folk-blues under the tutelage of Rice Miller and Big Walter Horton.

Arrival in Chicago

After some time in St. Louis, Missouri, Jacobs arrived in the nation’s blues capital city of Chicago in 1947. There, he quickly became a standout street corner performer and soon was asked to join the genre’s first truly dominant electrified ensemble, the blues band of McKinley “Muddy Waters” Morganfield, an older colleague whom Jacobs eventually eclipsed in technical capability, brilliant displays of musical virtuosity, and even commercial success, though never in reputation. Jacobs and Waters began recording together in 1949, and in October 1950 they recorded “Louisiana Blues” for the Chess label. Jacobs first recorded with an amplified harmonica in July 1951, debuting the technique that would set him apart from most of his contemporaries.

Jacobs was happy to seek out and benefit from the patronage of older, better-established figures in the Chicago blues scene. When he achieved his first and most well known hit in 1952 with the upbeat instrumental “Juke,” though, he immediately left Waters to form a band of his own, despite the fact that subsequent frequent personnel turnover indicated he was ill suited for the role of bandleader. Nonetheless, from 1952 to 1955 he racked up an unequalled string of hits, twelve straight rhythm and blues (R&B) releases, each of whose sales reached the top ten sales charts. He and Waters continued to record and perform together on and off for years, and some of Waters’s biggest hits were distinguished by Jacobs’s harmonica work, including “Trouble No More” and “I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man.” When national interest in rock ’n’ roll eclipsed that of R&B in 1955, however, Jacobs grew frustrated at declining sales and began overindulging in already-established alcoholism and physical altercations until his death in 1968 at the age of thirty-seven. “His once handsome features,” according to his most ardent biographers, were “reduced to a roadmap of scars.”

A Pioneer of Amplified Harmonica

Many may think of Jacobs primarily as a technical pioneer, using a small microphone cupped in his hands and fed through sets of powerful amplifiers and often iron-coned public address systems that allowed the musician to produce previously unheard of distortions when played at high volume. But as Tony Glover, Scott Dirks, and Ward Gaines, co-authors of The Little Walter Story: Blues with a Feeling (2002), as well as the liner notes to 2009’s Little Walter: The Complete Chess Masters 1950–1967 are forced to admit, “Walter was not the first harmonica player to amplify his instrument—identical equipment could be found in every blues joint from the 1940s onward.” Nonetheless, the same coauthors, each a professional blues musician to some extent, insist on describing him as creating “a totally new spectrum of sounds, sweetly sustained moans, razor sharp howls, and thundering chords, sounds that literally had never existed before.” They boldly assert that in blues harmonica, “there have been many great players, but only two distinct eras: pre-Little Walter and post-Little Walter.” The biographers also assert, “He began expanding the vocabulary [of the blues harmonica] with an approach like a jazz horn soloist … [setting] the harmonica free, granting it equality with every other instrument in the blues.”

Referring specifically to musical antecedents, biographer John Cohassey describes Jacobs’s approach as “fusing the style of his mentor John Lee (Sonny Boy) Williamson with the jump blues of saxophonist Louis Jordan. … A country-bred musician with a modern sensibility for swing music, Walter created an amplified sound filled with dark, haunting tones and flowing melodic lines that became an integral element in the emergence of Chicago blues.” The suggestion that Jacobs’s unique appeal might rest on his ability to straddle musical roles and musical worlds is also reflected in his dual roles as a sideman and bandleader. Former New York Times music correspondent Robert Palmer wrote the biographical notes to Jacob’s profile on the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame website, describing Little Walter’s supportive stance as a member of Waters’s band: “The harp lines wrap themselves around Muddy’s vocals, now chording like an organ, now filling melodically like a horn.” Popular music historian Bill Dahl, however, hears the solo bandleader Little Walter this way: “His daring instrumental innovations were so fresh, startling, and ahead of their time that they sometimes sported a jazz sensibility, soaring and swooping in front of snarling guitar and swing rhythms perfectly suited to Walter’s pioneering flights of fancy.”

Although passionate supporters hear the influence of his playing on generations, there has yet to be a harmonica player even barely suggested to be “the next Little Walter.” He did change the status of the harmonica from a novelty instrument, “the poor man’s saxophone,” to invest it with dignity. It may be that later electrification and stylistics fundamentals by themselves did the rest. Something along those lines is suggested by Buddy Guy, who was Jacobs’s Louisiana compatriot in the world of Chicago blues. “Like me, he was born in Louisiana and found himself trying to cope with the crazy blues life of Chicago,” Guy recalls in his 2010 biography, When I Left Home: My Story.

“Unlike me, though, he started something new. He invented something new. They say that King Oliver and Louis Armstrong invented the jazz trumpet. They say that Jelly Roll Morton invented the jazz piano. They say Charlie Christian invented the jazz guitar. They say Coleman Hawkins, Lester Young, and Charlie Parker invented the jazz saxophone. In that same breath you gotta say Little Walter invented the blues harmonica. No one had that sound before him. No one could make the thing cry like a baby and moan like a woman. No one could put pain in the harp and have it come out so pretty. No one understood that the harmonica—just as much as a trumpet, a trombone, or a saxophone—could have a voice that would stop you in your tracks, where all you could say was, ‘Lord, have mercy.’ … Before Little Walter, harmonicas cost a dime. Folks looked at them as toys. After Little Walter, harmonicas cost $5. Folks looked at them like instruments.”

Little Walter Jacobs died in Chicago in 1968 and was buried in St Mary’s Cemetery in Evergreen Park, Illinois.