Louis Armstrong

New Orleans–born musician Louis Armstrong helped introduce jazz to global audiences.

This entry is 8th Grade level View Full Entry

Louisiana State Museum

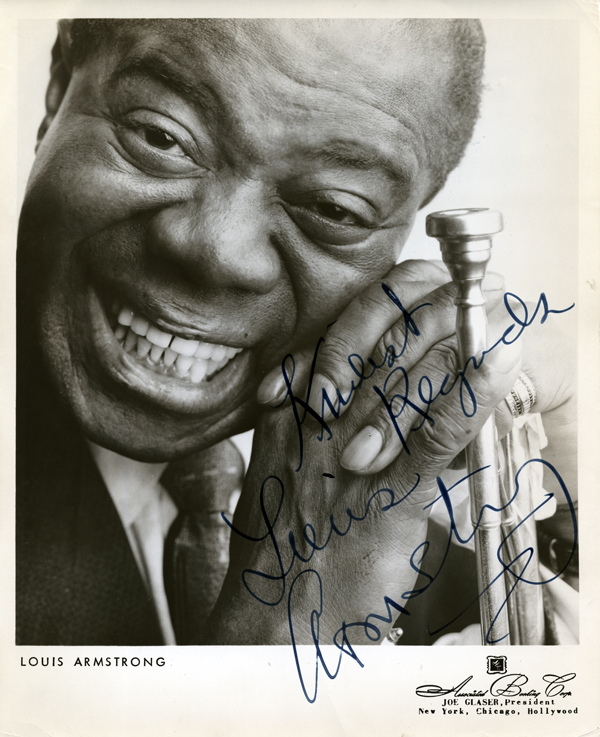

A signed photograph of Louis Armstrong, 1960.

Louis Armstrong is renowned as a towering figure in the evolution of jazz and, more broadly, as a major artistic figure of the twentieth century. One of several important second-generation jazz musicians to emerge from New Orleans in the 1920s, he helped introduce jazz to the world. In later years, Armstrong also became a pop music hero and beloved entertainer far beyond jazz’s relatively small audience.

What was Armstrong’s early life and career like?

Although Armstrong stated that he was born in New Orleans on July 4, 1900, his actual birth date was August 4, 1901. The son of Willie Armstrong and Mary Ann “Mayann” Miles of Boutte in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, he spent his early childhood with his grandmother, Josephine Armstrong. Louis Armstrong was raised on Jane Alley in a rough New Orleans neighborhood known as “back of town,” near the present-day corner of Tulane Avenue and Broad Street. “I sure had a ball growing up there as a kid,” Armstrong told Life magazine. “We were poor and everything like that, but music was all around you. Music kept you rolling.”

The music that Armstrong heard as a child was primarily a combination of blues, ragtime, military parade music, and spirituals. In the first decade of the twentieth century, this combination evolved into what would come to be called jazz. One important early source of music for Armstrong was a neighborhood joint known as the Funky Butt Hall. He wasn’t allowed inside but watched performances through holes in its ramshackle walls. Armstrong was also exposed to early jazz at second-line parades, funeral processions, and other community gatherings.

At the age of eleven, Armstrong began singing on the streets with a group of friends, accompanying them, at times, by playing a slide whistle. A year later he was arrested for illegally firing a pistol and sent to the Colored Waifs Home, a juvenile detention and reform school. There he learned to play the cornet and read music thanks to teacher/bandleader Peter Davis. Leaving the facility a year and a half later, Armstrong began performing at night while still doing manual labor by day. His reputation spread within the Black community and, at age eighteen, Armstrong was hired by trombonist Kid Ory to replace noted trumpeter Joseph “King” Oliver. Oliver, however, soon convinced Armstrong to join his band for a long-term gig in Chicago. This transition marked Armstrong’s emergence as a full-time professional musician with a burgeoning reputation. His fame was further enhanced by recording with Oliver’s band in 1923. Armstrong was also a featured soloist on records by diverse artists, including the great blues singer Bessie Smith in 1924 and Jimmie Rodgers, the first country music star, in 1930.

How did Armstrong’s career develop, and what has been his legacy?

Between 1925 and 1928 Armstrong made recordings with two groups whose members overlapped: the Hot Fives and Hot Sevens. These recordings have come to be lauded as definitive statements of classic New Orleans jazz, although this term wasn’t in use at the time. Highlights of these sessions included “Cornet Chop Suey,” “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” and “West End Blues.” For the next two decades, Armstrong played in a variety of settings, both as a bandleader and a sideman. He worked in small combos, big bands, and the orchestra for the all-Black musical Hot Chocolates. Armstrong also appeared in films and recorded with popular mainstream artists like Bing Crosby. As the big band era wound down after World War II, Armstrong returned to a smaller format with a band called the All-Stars.

In the social and cultural changes of mid-century America, Armstrong’s old-fashioned, gregarious performance style was seen as dated—and even offensive—in some circles. Armstrong’s 1949 appearance as King of Zulu, a then all-Black Mardi Gras parading krewe, further confounded some admirers. Some people in New Orleans’s Black community and beyond felt that Zulu’s tradition of painting members’ faces in blackface was demeaning to Black people. (Blackface continues to be a controversial part of Zulu’s tradition today.) Not understanding the parade’s cultural complexities and implicit satire, many fans were puzzled by Armstrong’s appearance in blackface—the Krewe of Zulu’s traditional attire—which was seen by many outside of New Orleans as offensive. At times critics—including modern jazz musicians and advocates of the 1960s Black Power movement—dismissed Armstrong as an “Uncle Tom,” despite his outspoken criticism of President Eisenhower’s handling of the 1957 school desegregation crisis in Little Rock, Arkansas. (The term “Uncle Tom,” which is sometimes used to describe Black people who act in a way that is seen as subservient to white people, comes from the lead character in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin.)

Such perceptions of Armstrong as outmoded continued until his death in 1971. But a decade or so later, Armstrong was lionized by such young talents as the New Orleans trumpeter Wynton Marsalis. Since then, the earliest aspects of Armstrong’s repertoire and technique—including vocal and instrumental improvisation—have again become very popular. In the twenty-first century, Louis Armstrong is appreciated as one of the most important musicians to emerge from Louisiana.