Louisiana Hayride

The Louisiana Hayride was a radio barn dance broadcast from Shreveport’s Municipal Auditorium between 1948 and 1960.

NOEL MEMORIAL LIBRARY, LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY IN SHREVEPORT

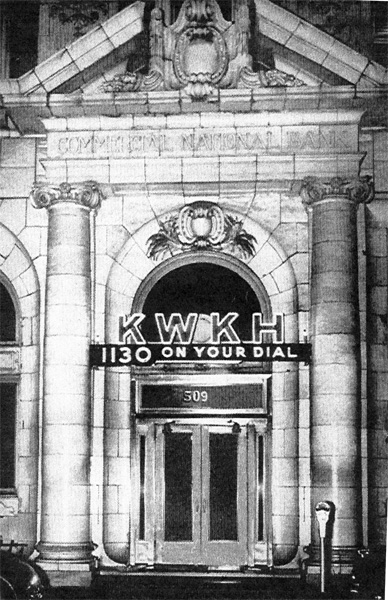

KWKH Radio Station.

The Louisiana Hayride was a radio barn dance broadcast from Shreveport’s Municipal Auditorium between 1948 and 1960. The show is perhaps most famous for spotlighting two icons of post-World War II American popular music—Hank Williams and Elvis Presley—at the beginning of their careers. Beginning in April 1948 Shreveport’s 50,000-watt station KWKH broadcast the weekly musical variety show every Saturday night. Many of the era’s country music icons gained their first national exposure and launched enduring careers from the Hayride stage. Besides Williams and Presley, Hayride artists included Red Sovine, Slim Whitman, Webb Pierce, Faron Young, Billy Walker, Jim Reeves, Floyd Cramer, the Browns, Johnny Cash, George Jones, Jimmie C. Newman, and Johnny Horton.

The Hayride broadcast could be heard as far north as Chicago and as far west as Los Angeles. Among many examples of this once-popular entertainment format, the Hayride stands out as second in significance only to Nashville’s Grand Ole Opry, which played the role of gatekeeper among established artists. Newer artists, in contrast, looked to the Louisiana Hayride as a place to initiate their careers. Hank Williams was the first in a long line of country music artists whose regional and early recording success earned them a place in the Hayride cast; in turn, they gained a broad audience on the Hayride and then moved on to Nashville’s Opry. The pattern was so established that the Hayride adopted the moniker “Cradle of the Stars.”

The Hayride’s Success

The Hayride’s success resulted from the happy confluence of several factors. One was the power of radio station KWKH, whose AM signal maxed out the federally established limits. Popular country music performers like the Bailes Brothers and Johnnie and Jack, with Kitty Wells, could be heard in its first broadcasts. Early in its history, the Hayride’s radio market expanded via the Universal network, an independent network of twenty-five stations, of which KWKH was a part. The market again expanded by February 1950 with the Louisiana Hayride network, which linked twenty-seven stations across four states. By late 1952, sister station KTHS in Little Rock, Arkansas, also 50,000 watts, began airing a simultaneous broadcast of the Hayride. Finally, in 1953, CBS radio picked up a thirty-minute live segment of the show to be aired every third Saturday over its national network of more than 200 stations. The Far East Network of the Armed Forces Radio Services began airing a weekly thirty-minute segment in June 1954.

Local factors also account for the Hayride’s success. The relatively late arrival of television to the Shreveport market helped maintain a live audience that averaged around 3,300 people. Barksdale Air Force Base provided a steady clientele for the “Bossier strip,” an area of clubs and nightspots that supported the local musicians who also played the Saturday broadcast. The region also saw a flowering of independent record labels that wanted to place their artists on the show. Furthermore, the Hayride developed a distinctive character. In part, this distinctiveness stemmed from the individual personalities whose vision shaped the show. In addition, the constant necessity of finding new talent to fill voids left by its steady stream of Nashville-bound artists kept the Hayride fresh and innovative. The Hayride’s character also reflected the social milieu from which it emerged. Located at a cultural crossroads where the Deep South meets the frontier West, Shreveport incorporated elements of both cultures.

The Louisiana Hayride and Rock and Roll

Hayride engineer Bob Sullivan once quipped, “That show wasn’t produced, it just happened.” In 1954, the freewheeling attitude among Hayride producers led to the booking of a young singer named Elvis Presley, who had already been rejected by the Opry. Like others before him, Presley found a national audience during his year-and-a-half-long stint on Hayride. Difficult to categorize at the time, his style blended elements of country, rhythm and blues, and gospel, the music he loved growing up around Memphis, Tennessee. This musical amalgam eventually came to be known as rockabilly, a subgenre of rock and roll, whose rise parallels the social and cultural shifts of the late 1950s most dramatically marked by Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark US Supreme Court case ruling that deemed racial segregation in schools unconstitutional. Presley’s early association with the Hayride sealed the show’s place in media history.

Lesser-known musicians nurtured by the Hayride include James Burton, D. J. Fontana, and Jerry Kennedy, each of whom cut their teeth as young musicians on the show. Joe Osborn, whose innovations on bass provided the foundation for the Los Angeles studio sound that dominated mainstream FM radio in the late 1960s, also grew up in the area but was not as closely associated with the Hayride. Each of these musicians experienced the same gestalt of Black and white musical culture that Presley captured in his earliest Sun Records releases and broadcast over KWKH on Saturday nights during the mid-1950s.

The Hayride continued to broadcast regularly into 1960, the year when its last significant performer, Johnny Horton, died in an automobile accident. Yet even before Horton’s death, Hayride audiences gradually diminished. Some blamed the show’s decline on the demographic shift in audiences that happened during Presley’s tenure: young, demonstrative fans began appearing in droves, driving away the older, more sedate crowd who had sustained the show in its early years. Presley’s departure left the Hayride with a lack of stability for either fan base. Others suggest that television’s entry in the regional market made people less inclined to go out for live entertainment on a Saturday night. Still others blame Shreveport’s civic leaders or KWKH executives, who were slow to realize the potential of Shreveport’s musical treasure. It could be simply that this bright star in Louisiana’s musical horizon had run its natural course and, as stars do, died away.

Although irregular broadcasts continued into the 1960s, and the live show was even revived for a while during the 1970s, the Hayride is best remembered as the radio barn dance that emerged from deep currents of commerce, culture, and media in northern Louisiana, resonated with the energy and vitality of both country music and rock-and-roll, and sent ripples of influence into U.S. popular music during the post-World War II decade and beyond.