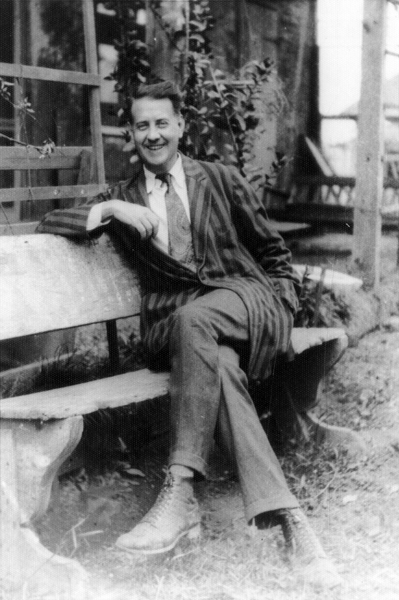

Lyle Saxon

Lyle Saxon published articles, short stories, books of creative nonfiction, and one novel; he also directed the Louisiana branch of the Federal Writers Project.

Courtesy of State Library of Louisiana

Lyle Saxon. Unidentified

Once known as “Mr. New Orleans” or “the dean of New Orleans writers,” Lyle Saxon published scores of articles and short stories for The Times-Picayune, four books of creative nonfiction, and one novel. During his brief but productive literary career, Saxon also directed the Louisiana branch of the Federal Writers’ Project, a New Deal program overseen by the Works Projects Administration (WPA). A longtime resident of the French Quarter, Saxon advocated the preservation of the neighborhood’s historic homes and encouraged other writers and artists to live, work, and/or visit the community, helping to spark a renaissance in the area.

Early Life

Born September 4, 1891, Lyle Chambers Saxon spent his early years in Baton Rouge. The child of Katherine Chambers and Hugh Allan Saxon, Saxon was raised by his mother and her family. His maternal grandfather owned the first bookstore in Baton Rouge, and both his paternal grandmother and his mother were journalists. Not surprisingly, perhaps, Saxon became a newspaper reporter after attending Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. As a journalist, he worked briefly in Chicago, later in Baton Rouge, and eventually in New Orleans.

In the late 1920s, however, Saxon left full-time newspaper work and gravitated toward a literary career. He published an early short story, “Cane River,” in the prestigious magazine The Dial, edited by Marianne Moore. Another early Saxon story, the odd and remarkable “The Centaur Plays Croquet,” was included in The American Caravan, an anthology edited by Van Wyck Brooks and Lewis Mumford, among others.

Creative Nonfiction and the Novel

The first of Saxon’s popular nonfiction books, Father Mississippi, grew out of the devastating 1927 Mississippi River floods. Century Publishing Company paid Saxon to contribute articles on the floods to Century Magazine, which led to a book about his experiences accompanying the U.S. Coast Guard on rescue missions. The success of Father Mississippi was followed by Century’s publication of Saxon’s Fabulous New Orleans in 1928, Old Louisiana in 1929, and Lafitte the Pirate in 1930. These books—part history, part travelogue, and part fiction—sold quite well over a number of years. Lafitte the Pirate earned Saxon additional recognition when it was adapted for the screen in the 1938 film The Buccaneer, directed by Cecil B. De Mille.

After long delays and countless starts and stops, Saxon was finally able to complete his dream project in 1937: his first and only novel, Children of Strangers. Saxon wrote much of the book while in residence at Melrose Plantation in the Cane River region of Natchitoches Parish, where the novel is set. The main character is of mixed African and Caucasian heritage; Saxon’s treatment of her relationships with white, mixed-blood, and black men was controversial for many contemporary readers. Regional reactions to Children of Strangers were predictable: Carl Van Doren praised the novel in the Boston Herald, while the reviewer in The Times-Picayune contended that the book was “not good reading for Southerners.” Saxon’s novel also brought him what many writers of the day would have considered a great honor: he was featured on the cover of the July 10, 1937, issue of The Saturday Review of Literature, which contained a laudatory review of Children of Strangers.

Saxon and the Federal Writers’ Project

The latter part of Saxon’s career was devoted primarily to work growing out of the WPA Federal Writers’ Project in Louisiana and, later, in Washington, D.C. Named state director of the project in 1935, Saxon supervised about a hundred field workers, who interviewed thousands of Louisianans. The project resulted in the New Orleans City Guide (1938), Louisiana: A Guide to the State (1941), and Gumbo Ya-Ya (1945). Several reviewers lauded the state guidebook, one of the longest in the country. A New York Herald Tribune writer lamented that every state was not fortunate enough to have Lyle Saxon as the editor of its guide. Saxon’s work with the WPA was rewarding financially, but also exhausting and demanding. He saw the project through until its end in 1943, but published little of his own fiction during the last few years of his involvement with it.

Saxon’s Legacy

Saxon was unusually well known and well liked among his fellow writers. A consummate host and gifted raconteur, he entertained at his homes in the French Quarter (he had three), his Christopher Street apartment in Greenwich Village, his quarters at Yucca House on Melrose Plantation, and his suite at the St. Charles Hotel in New Orleans. His literary friends included Sherwood Anderson, William Faulkner, Roark Bradford, Edmund Wilson, Elinor Wylie, John Dos Passos, John Steinbeck, Thomas Wolfe, Edna Ferber, and Sinclair Lewis. A number of Faulkner’s biographers, in fact, have mentioned Saxon’s role in encouraging the young Mississippian in his early years.

Not as well known was the pivotal role Saxon played in the French Quarter renaissance of the 1920s and 1930s. By 1920, when the author first moved there, the Quarter had become a badly deteriorating and dangerous part of the city. Saxon restored a number of houses there, encouraged friends to join him, and championed the area in The Times-Picayune. Saxon’s friend Robert Tallant contended that the writer played a major role in “saving the Quarter” and in its rebirth as “more an art colony, less an underworld.”

By early 1946, Lyle Saxon was gravely ill with cancer. Yet he managed to write a bit about Mardi Gras for The Times-Picayune, as he had done for many years before. In addition, he participated in the Mutual Radio Network’s broadcast of the Rex parade. It is fitting that his last public words were devoted to describing a famous activity so identified with the city he loved. A few weeks later, on April 9, 1946, Saxon died in New Orleans, at the age of 54, from complications following surgery.

By his own admission, Saxon often struggled with alcoholism, chronic health problems, laziness, and procrastination. Nevertheless, he wrote or edited eight books, as well as numerous features, reviews, short stories, and newspaper articles. Though “Mr. New Orleans” might have accomplished more, he did accomplish much in a relatively brief lifetime.