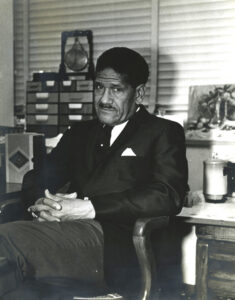

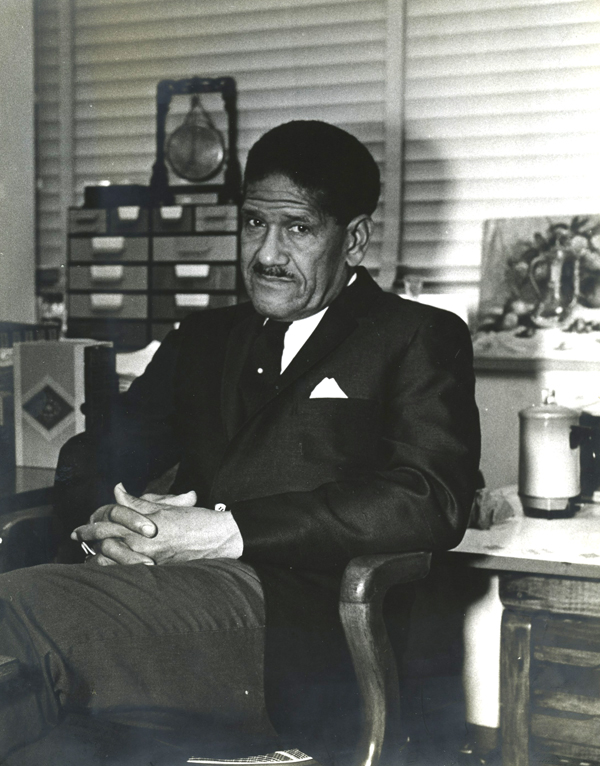

Marcus Christian

Marcus Christian was a Louisiana writer, folklorist, and historian, known as the author of poems which satirize Jim Crow laws.

Courtesy of Earl K. Long Library, University of New Orleans.

A black and white reproduction of a photograph of Louisiana writer, Marcus Christian.

Twentieth-century Louisiana writer, folklorist, and historian Marcus Christian is perhaps best known as the author of more than one thousand poems, many of them published in anthologies, newspapers, and journals. His poetry, some of which was collected in I Am New Orleans and Other Poems, often satirizes the narrow limitations imposed on people of color by those who enforced the principles of Jim Crow. Christian was also an important writer of nonfiction and history. While working for the Louisiana Writers Project at Dillard University, Christian helped compile one of the few histories of the state written by an African American. Though still unpublished, the manuscript provides a wealth of information about the state’s history and folklife, and continues to inform contemporary studies of the region.

Early Life

Born on March 8, 1900, in rural Terrebonne Parish, Marcus Bruce Christian was the son of Emanuel Banks Christian and Rebecca Harris Christian, and the fourth of six children. Christian’s mother died when he was only three years old, and his father died when he was thirteen. His father and grandfather, a former slave, were both teachers and Christian benefited from their knowledge, as well as his early academic training at the Houma Academy. After his father’s death, Christian gradually took responsibility for supporting his siblings. At the age of nineteen, he moved the family to New Orleans where he set up a dry-cleaning business. In the evenings, he went to school, wrote poetry, and developed his love of literature.

Christian published some of his early poems in African-American oriented publications such as Opportunity, The Crisis, and Louisiana Weekly. At the latter publication, he also served as poetry editor, a position he used to promote the work of other New Orleans writers. The 1934 publication of his poem “McDonough Day in New Orleans” in the New York Herald Tribune helped bring his work to national attention. Christian corresponded with Arna Wendell Bontemps and Langston Hughes, among other writers active in the Harlem Renaissance, while remaining in New Orleans. Though geographically removed from this literary movement, Christian published poems on similar racial themes such as segregation, lynching, and poverty.The Dillard History Unit

In 1936, Christian became the director of the Dillard History Unit, an all-black affiliate of the Louisiana Writers Project (LWP). Directed by writer Lyle Saxon, the LWP was a state branch of the Federal Writers Project, a program designed to employ out-of-work writers and editors during the Great Depression. Between 1936 and 1942, Christian oversaw and edited the work of writers including James B. LaFourche, Homer McEwen, Clarence A. Laws, Octave Lilly, Eugene B. Willman, and Alice Ward-Smith. Their mission was to recover the history, folklore, and culture of African Americans in Louisiana.

Exploring more than three hundred years of Louisiana history, the writers thoroughly researched the Creole dialect, the genealogy of Creole families, and the African origins of some slave traditions, skills, and crafts, among other topics. They also examined the lives of Marie Laveau, the so-called Voudou priestess of New Orleans, and Bras Coupé, a legendary runaway slave, attempting to sort fact from fiction. Parts of the group’s research were included in the LWP publications The New Orleans City Guide (1938), Louisiana: a Guide to the State(1941), and Gumbo Ya-Ya (1945).

In addition, Christian incorporated many of their findings into his study of blacks in Louisiana. More than 1,200 pages in length, his manuscript lacked an official title, but has been referred to as The History of the Negro in Louisiana, The History of Black Louisiana, and The Negro in Louisiana. Never published in its entirety, the manuscript is housed in the University of New Orleans’s special collections, where it is available electronically.

Christian continued as assistant librarian at Dillard University for seven years after the LWP ended. With the help of Lyle Saxon, he successfully applied for a Rosenwald Grant that allowed him to continue working on his historical study. The project, however, was never completed. In 1950, Christian left Dillard, and for several years lived in a state of near-poverty, working part-time as a printer and as a deliveryman for The Times-Picayune. In 1968, University of New Orleans history professors Joseph Logsdon and Jerah Johnson, then chair of the department, offered Christian a special position in the history department. In that year, Christian published the long poem, “I Am New Orleans,” printed in commemoration of the 250th anniversary of the founding of New Orleans. In the poem, the speaker narrates many stories about New Orleanians. He celebrates the city’s founding and folklife, explores its epidemics and wars, and surveys the immigrant groups that have called the city home. Christian went on to become writer-in-residence at the University of New Orleans, and in 1972 he published the nonfiction study Negro Ironworkers in Louisiana.

On November 21, 1976, soon after falling down in his University of New Orleans classroom, Marcus Christian died. The Marcus Christian Collection at the University of New Orleans continues to preserve many of his papers, as well as more than one thousand of his poems. The collection also includes manuscripts—including unpublished plays and short stories—and Christian’s correspondence with individuals including Eleanor Roosevelt, Langston Hughes, A. P. Tureaud, Sterling Brown, W. E. B. Dubois, and John Blassingame.