Michael Deas

Michael Deas is a New Orleans artist who has gained acclaim with his high-profile commissions of famous Americans' portraits.

Courtesy of The Goldring Collection

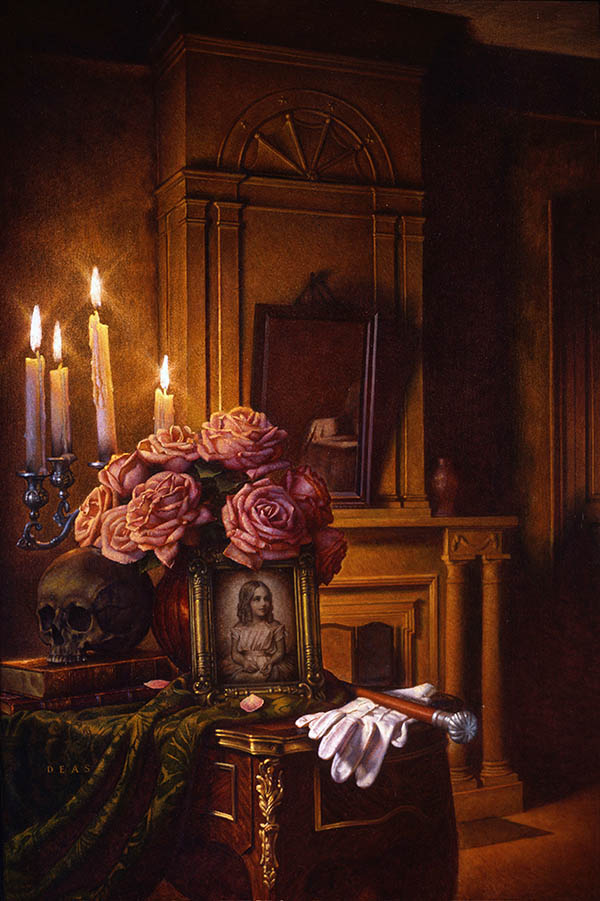

Interview with a Vampire. Deas, Michael J. (artist)

New Orleans artist Michael J. Deas has gained acclaim with his high-profile commissions for portraits of famous Americans that have graced book and magazine covers as well as US postage stamps. In 1992 he was commissioned to update the iconic, redheaded, torch-bearing “Columbia Lady” seen in the opening credits of all movies made by Columbia Studios. Deas prefers to call his style of painting “classical” rather than super-realistic or photorealistic, categorizations often applied by art scholars.

Born in 1956, Deas was the son of a US Navy officer then stationed in Norfolk, Virginia. At the age of three months, Deas moved with his family to his father’s native New Orleans, where they resided for the next five years. Although the family moved to suburban Long Island in New York, Deas continued to visit New Orleans well into his teens and considers New Orleans his hometown.

Deas’s intimate ties to New Orleans have had a profound effect on his art. His aesthetic is influenced by the city’s grand oak trees, ancient houses, and ruined cemeteries. One of his earliest childhood memories is of climbing his grandmother’s bookcases in search of Clarence John Laughlin’s iconic book of photography, Ghosts along the Mississippi. Deas attributes to Laughlin’s lasting influence on his art the pervasive sense of melancholy, revealed much more so in Deas’s recent, more emotional and introspective works. Even as a child, he was drawn to the nostalgia and mystery of the deteriorating architecture and romantic landscape of South Louisiana, begging his father to drive him down the River Road to see the ruins.

A Realist Among Abstractionists

At a very early age, Deas showed an unusual proclivity for drawing. In 1974, he enrolled at Pratt Institute, a private art school in Brooklyn, New York. He remembers Pratt as a disastrous experience. At that time, realism—his preferred method of artistic expression—was at its lowest ebb. Deas recalls that, in the 1960s, Alfred Lord Leighton’s magnum opus of 1895, Flaming June, failed to reach a minimum bid of $140 at auction. He also remembers his days of walking down East 51st Street in New York City, at the age of 25, and regularly visiting a gallery that had original works by such traditionalists as William-Adolphe Bouguereau, John William Waterhouse, and Sir Lawrence Alma Tadema. Their artworks, Deas says, were “stacked on the floor like kindling wood, in their original frames.”

Minimalism, conceptual art, and abstract expressionism were the dominant styles of the art schools during Deas’s formal art education; all of his instructors derided representational art. By Deas’s senior year at Pratt, only two representational artists were left in the department—Deas and Steven Assael, who is nationally recognized today as one of his generation’s greatest representational painters. “I learned more from Steven in a few hours about composition and technique than I did in four years of art school,” Deas says.

Using a combination of time-honored techniques—grisaille (where the image is executed in black-and-white first and then completely rendered) and imprimatura (a toned wash over the painting)—Deas builds his surfaces, using gradual layers. “I’ve always been in love with realism and have never been willing to give it up,” he admits.

Deas dropped out of Pratt twice—the second time roughly three months before he was scheduled to graduate. His main education came from the brief time he spent with Assael; by reading as much as possible from old texts on painting; and through spending many hours in the New York City museums, especially the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Frick Museum, and The Cloisters. There, he would closely study the techniques of master realist painters, often setting up an easel and copying their paintings. Although Deas did eventually earn his degree (almost a decade later), he still considers himself largely a self-taught painter. The irony of his Pratt instructors—all fully tenured professors—deriding his work as academic is something that has stayed with Deas throughout his career.

After leaving Pratt the second time, Deas supported himself through illustration work, mainly for textbooks and advertising. Around 1980 Deas received his first serious illustration assignment: an image for the promotion of Werner Herzog’s film Aguirre: The Wrath of God. Afterward, he received a phone call from the German filmmaker himself, who praised Deas’s work by saying, “I have seen many posters for my movie in many languages and in many countries, but the painting you did is by far the best version I have seen of Aguirre.”

Return to New Orleans

After maintaining a studio in Brooklyn Heights for many years, Deas returned to New Orleans in 1988. It was the fulfillment of his lifelong dream to live in the French Quarter. Taking a small studio in the 500 block of Governor Nicholls Street, Deas felt that not only had he returned home, but also he had returned to the last frontier of bohemia: the French Quarter, a place with a long and storied history of creativity and freedom. Working in that tiny studio, Deas painted The Letter (1990), a commissioned work for the cover of a novel. For this painting Deas garnered his first gold medal from the Society of Illustrators. He has since won a total of five gold medals and two silver medals.

After leaving the Governor Nicholls studio, Deas took another a few blocks away at Toulouse and Royal streets, just a few doors down from the apartment where Tennessee Williams lived and wrote his earliest plays in the 1930s. A longtime admirer of Williams, Deas completed a painting of the writer that became the image used for the US postage stamp Literary Arts Series: Tennessee Williams, which was issued in 1995. It was his first stamp published by the US Postal Service. To date, Deas has created artwork for more than twenty postage stamps, including images of Marilyn Monroe, James Dean, Katherine Anne Porter, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, Humphrey Bogart, Cary Grant, Audrey Hepburn, and Edgar Allen Poe. Several portraits—including those of Theodore Roosevelt, Benjamin Franklin, and Mark Twain—were also commissioned for the cover of Time magazine.

The crowning achievement of Deas’s career as an illustrator came in 1992, when Columbia Pictures commissioned him to paint a new version of its famous “Columbia Lady” logo. For a model, he chose a young woman who worked at the New Orleans Times-Picayune newspaper, Jenny Joseph. Deas remembers searching for just the right model when he found Joseph. “She was elegant, tall, beautiful, and classy,” he remembers. “I knew I had found the right one.” He then spent weeks riding his bicycle around New Orleans, looking for the perfect clouds. “One day, I looked out my window and saw this huge bank of cumulus clouds over the Mississippi River. I grabbed my bike and rode like crazy to the Crescent City Connection.”

“Those are New Orleans clouds,” Deas says of the finished work seen at the beginning of all films by Columbia Pictures. “It is very much a New Orleans-based image, in many ways.”

Deas continues to paint in the French Quarter, where he purchased a home in 1999. While he still works as an illustrator, he recently created a body of works of a deeply personal and often highly allegorical nature that are marked with an elegant eye and a mastery of the oil medium, which is unusual in a contemporary context. Deas explains: “I feel that technique is separate from the subject matter. There is something inherently beautiful about a wonderfully crafted representational painting that is utterly satisfying to the viewer. I feel, though, that what I am trying to do is add a more symbolic or allegorical aspect to my work. Realism is more than painting a pear and a teapot. You can convey something more profound.”