Milliken’s Bend

At Milliken’s Bend the majority of Union forces were formerly enslaved men whose valor was heralded to increase military recruitment among free African Americans.

Wikimedia Commons

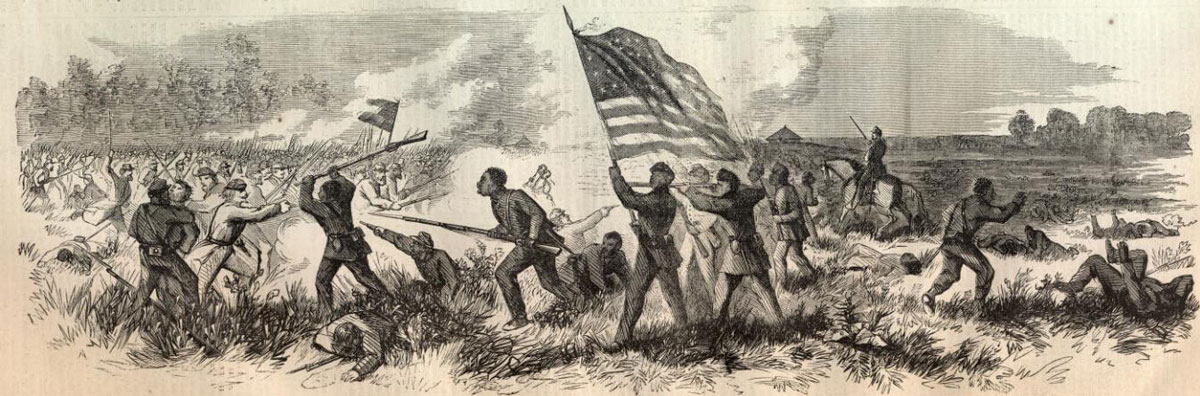

Illustration of the Battle of Milliken's Bend, June 7, 1863. Theodore Russel Davis, illustrator; Harper's Weekly, publisher.

The Civil War battle of Millikenʼs Bend took place on June 7, 1863, on the Mississippi River near the shared border of present-day Madison and East Carroll Parishes as part of the Union’s Vicksburg campaign. It was a small battle, with approximately 1,500 men engaged on each side. It is noteworthy for its role in the history of African American troops during the Civil War. It is significant for three main reasons. First, it proved to a skeptical white Northern public that Black troops could fight with courage and tenacity. Second, accusations that Confederate forces executed white and Black prisoners of war in the aftermath of the battle contributed to the breakdown of prisoner exchanges between North and South. Lastly, news of the heroism of the “African Brigade” encouraged Northern whites to support the use of Black troops during the Civil War.

The Battle

In the early morning hours of June 7, 1863, a Confederate force of Texans led by Brigadier General Henry McCulloch attacked the Union outpost at Millikenʼs Bend. Its defenders were known as the “African Brigade,” composed of newly recruited, formerly enslaved African American troops with white officers. Their temporary commander was Swiss immigrant Col. Hermann Lieb. The African Brigade was also supported by 125 men of the all-white 23rd Iowa Infantry, the only combat-tested troops present on either side.

Initially hoping to disrupt Union Major General Ulysses S. Grantʼs supply lines, the Confederate command discovered too late that Millikenʼs Bend was no longer the large supply depot it had been only a month or so before. Compelled to at least make some show of attempting to relieve the besieged Confederate forces at Vicksburg, McCulloch and two other brigades were ordered to attack Union outposts on the Mississippi River. Only McCullochʼs men engaged the enemy; the other two efforts were abandoned.

The Confederates attacked at dawn and hoped to drive the Union forces into the river. The African Brigade put up stubborn resistance in vicious hand-to-hand combat, but they were overwhelmed and forced to the riverbank. Meanwhile, a small number of men from the 11th Louisiana Infantry (African Descent) held firm at the far end of the Union line, causing the Confederate advance to stall. Union gunboats arrived and began shelling the Confederates. McCulloch realized he could no longer sustain the attack, and the Southern forces withdrew.

Both sides were shocked at the severity of fighting and the number of casualties. The African Brigade lost nearly a third of its men. The 9th Louisiana Infantry (African Descent) had sixty-six men die on the battlefield—the largest loss by any Union regiment, Black or white, in a single engagement during the entire Vicksburg campaign. McCullochʼs Confederate brigade lost nearly two hundred men. One experienced Union soldier declared the battle worse than Shiloh, a battle known for its severity.

Aftermath and Significance

Because Millikenʼs Bend was no longer a major supply depot for the Union army and the Confederates had failed to capture it, the battle had little immediate significance. In that sense it was a wasted effort. However, the battle at Millikenʼs Bend holds outsized significance in the story of African American troops in the Civil War.

Most of the Union soldiers at this battle were formerly enslaved individuals. Just a few weeks or months before, they had been held in bondage on nearby cotton plantations. Because none had been in the service for more than a month, they had received minimal training and were given poor weaponry. No one thought they were ready to face the enemy. The Black men of the African Brigade surprised everyone with their tenacity and courage. As was the custom of the time, white officers commanded the Black enlisted men. One Union commander praised the troops, writing, “I think there will be a future that will make this first regular battle against the Blacks alone honorably historic.” Even McCulloch commended their efforts, stating that they fought “with considerable obstinacy.”

African American troops fought in other battles during the summer of 1863, such as the Siege of Port Hudson and the assault on Fort Wagner, South Carolina. In these cases, many of the Black troops were free men and were part of larger operations attached to predominantly white troops. Only at Millikenʼs Bend was the majority of the Union force composed of formerly enslaved men. The valor of Black troops at Millikenʼs Bend was heralded throughout the North to increase recruitment among free African Americans. Black leader and abolitionist Frederick Douglass proclaimed their courage in a well-publicized broadside.

Confederate and state laws called for the re-enslavement or execution of Black men captured in battle, and their white officers could be accused of leading a “slave insurrection” and put to death for their crime. Almost immediately after Millikenʼs Bend, accusations that Union prisoners of war had been executed began to swirl around Grantʼs headquarters. Grant inquired with Confederate Major General Richard Taylor if there had been executions, and Taylor denied the accusations. But later evidence proved that at least two white officers, and perhaps some Black enlisted men who had been captured at Millikenʼs Bend, were executed near Monroe when the town was under the command of former Louisiana governor, Brigadier General Paul Octave Hebert. A report about these executions made its way to the US Secretary of War and was submitted as evidence to a Congressional investigating committee. This testimony played a contributing role in the breakdown of prisoner exchanges between North and South. The federal government stopped the system of prisoner exchanges, which led to unprecedented suffering in both Northern and Southern prisoner-of-war camps.