Morris Henry Hobbs

A native of the Midwest, Morris Henry Hobbs joined the French Quarter artists community in 1939 and spent the rest of his life producing images of New Orleans and its inhabitants.

Courtesy of Ogden Museum of Southern Art

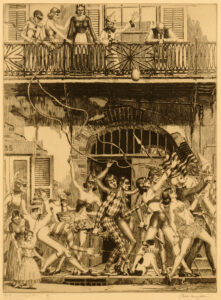

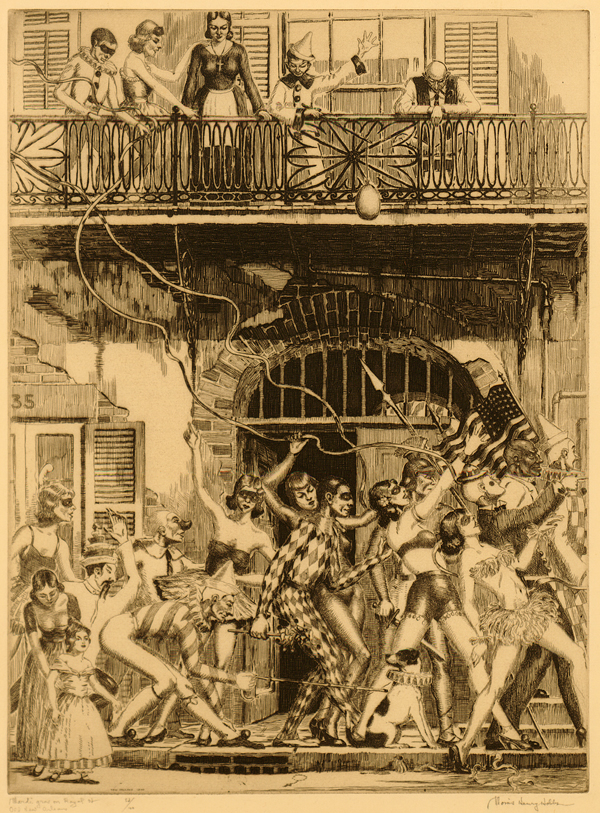

Mardi Gras. Hobbs, Morris Henry (Artist)

Talented printmaker and architectural draftsman Morris Henry Hobbs discovered inspiration in the French Quarter’s historic buildings for his enduringly popular series of prints collectively titled Old New Orleans. In 1938 this native Midwesterner made his first sketching trip to New Orleans, where he found the Vieux Carré’s enclave of artists and writers welcoming and their chosen decrepit environs of Creole townhouses, lush courtyards, and filigreed balconies stimulating. Concerned about the haphazard and insensitive renovations of the city’s historical buildings in the 1930s and 1940s, Hobbs envisioned his Old New Orleans series as both an artistic endeavor and a crusade to document imperiled buildings. His attention to detail, accurate proportions, and sensitivity to the nuances of the picturesque structures attest to his formal training as an architect.

Education and Early Training

Hobbs was born on January 1, 1892, in Rockford, Illinois. As the son of a watchmaker, Hobbs inherited his father George’s natural dexterity. He apprenticed in the family’s watch shop in Rockford, where the elder Hobbs delighted in his only child’s meticulous craftsmanship. At the turn of the century, the family moved to Chicago, where Morris pursued an education in architecture, studying with private tutors and at the Illinois Institute of Technology. Despite his father’s objections, he took evening drawing classes at the Art Institute of Chicago.

Hobbs worked in the architectural field until World War I intervened. In 1918 he enlisted in the American Expeditionary Forces; while abroad, he was stricken by the flu epidemic rampant in Europe at the time. The disease irreparably damaged his hearing and left him virtually deaf. Hobbs, who was only in his late twenties, would become proficient in reading lips and thereafter wore hearing devices.

Upon his military discharge, Hobbs joined Frank Chase’s architectural firm in Chicago. He soon found his deafness made it difficult to communicate with his clients, so he decided to focus on working as a draftsman. It was at the firm that he met his first wife, Julia (Jewel) Clark, who worked as the secretary and bookkeeper. After their marriage in 1921, the young couple moved to Toledo, Ohio, where he eventually became a partner in the Gerow, Conklin, and Hobbs architectural firm. The couple had two daughters.

Career as an Artist Begins

In Toledo, the Hobbses were befriended by the artists J. Ernest and Grace Dean. The Deans had studied printmaking in Munich, Germany, and introduced Hobbs to the medium. Printmaking, with its emphasis on line drawing, is similar to architectural work, and it suited Hobbs.

In the early to mid-twentieth century, the Second Etching Revival renewed interest in fine art prints and fostered the proliferation of etching clubs in America. The clubs organized traveling exhibitions, lecturing series, and demonstrations. Hobbs actively participated and exhibited with the Toledo Society of Etchers, the Chicago Society of Etchers, and the Miniature Print Society, and he later was a founding member of the Louisiana Society of Etchers. The acceptance of one of his prints at the prestigious Brooklyn Society of Etchers in 1926 was an early validation of his talent. Ignoring the emerging modernist movement of the early twentieth century, Hobbs preferred to work in a representational style, following in the tradition of James McNeil Whistler and John Taylor Arms.

In 1925 Hobbs and his family returned to Chicago, where he worked as a draftsman for the Craven and Mager architectural firm. Tragically, both partners drowned in a boating accident in 1928 and the firm closed. With the stock market crash and the Great Depression, Hobbs was unemployed with no imminent job opportunities. He decided to devote himself to creating art, focusing primarily on printmaking. He took classes, returned to France on an extended sketching trip, submitted his prints for exhibitions, and by 1931, rented a studio in the Tree Studio Building.

Hobbs earned recognition and such accolades as having his works printed in the 1931 book Contemporary American Etchers, in the Pencil Point and Print Collector’s Quarterly journals, and in the 1930 and 1935 editions of Fine Prints of the Year. In 1936 he was selected by the Associated American Artists of New York for their subscription print series, and he was given a solo show of his architectural views and nudes prints by the Division of Graphic Arts of the Smithsonian Institution.

Old New Orleans

After his visit to New Orleans in the winter of 1938 and amid positive reviews of his Old New Orleans series, Hobbs made a second trip to the city in January 1939. He brought with him two large printing presses so that he would no longer have to wait to print his etchings. As an established artist, he actively participated in the thriving community of artists during what came to be known as the French Quarter Renaissance by joining the New Orleans Art League, the Art Association of New Orleans, and the Arts and Crafts Club. Hobbs established a relationship with Harmanson’s Art and Bookstore on Royal Street. There, his prints were sold to tourists and locals alike along with printed postcards and calendars illustrated with his artwork. He never returned to Chicago and instead asked Alice Seddon, a woman who would become his second wife, to close his studio. New Orleans became the artist’s adopted home and inspiration for his work.

Hobbs moved his printing presses into his studio in the Art League building on Toulouse Street and concentrated on expanding Old New Orleans. Hobbs was dismayed by the arbitrary renovations and modernization occurring in the French Quarter as the neighborhood began to draw tourists and bohemian residents. He envisioned his Old New Orleans series as a way to document a time and place and as a means to advocate for the preservation of the historic neighborhood. The prints continue to be highly regarded, with extensive holdings at Tulane University and The Historic New Orleans Collection.

In 1939 Hobbs had the distinction of being honored at the Smithsonian Institution with a second solo exhibition that featured the Old New Orleans series. Eventually, he returned to architecture to supplement his income by working as chief designer for Favrot, Reed, Mathes, and Bergman. By the 1950s he had become an avid collector of tropical bromeliad plants and cofounded the Bromeliad Society of Louisiana. At his home in Mandeville, Hobbs maintained a greenhouse, where he focused on painting watercolors for a proposed but never completed book, Bromeliads and Birds of Tropical America.

Hobbs’s work is represented in many public and private collections, including the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans, the University of New Orleans, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the New York Public Library, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco.

After a brief illness, Hobbs died in New Orleans on January 24, 1967.