Paul Barbarin

Jazz musician Paul Barbarin was a pioneer and leading representative of classic New Orleans drumming.

Courtesy of William Carter

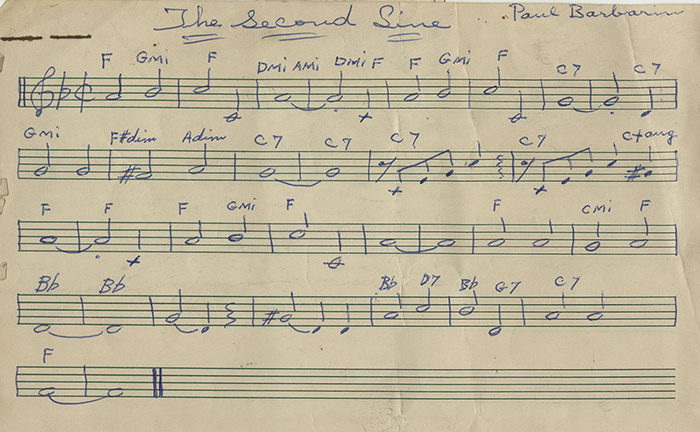

The Second Line. Barbarin, Paul (Composer)

Adolphe Paul “T-Boy” Barbarin was a New Orleans jazz drummer among the pantheon of first-generation musicians from the earliest days of the musical genre. He claimed (as have other pioneer drummers) to have innovated the playing of rhythmic patterns on the cymbal—a practice that has long since become standard. He was known for his crisp, dry, and at times almost muffled, tone on the snare drum, contrasting with the warm, full-bodied timbre of his bass drum and tom.

Born into a musical family in 1899 (he varied his year of birth in interviews), Barbarin grew up in the Creole Treme neighborhood of New Orleans. His father, Isidore, was a renowned horn player; his maternal uncle, Louis Arthidore, was a legendary clarinetist; and his brother Louis also was a famous drummer. Barbarin taught himself to play the drums, briefly studied clarinet with his godfather, Paul Chaligny, and by the mid-1910s was playing with well-known local bands. In 1917 he moved to Chicago, Illinois, and worked in the stockyards but soon found musical work. During the following five years he performed at Chicago’s Royal Gardens and toured through the Midwest and Canada before returning to New Orleans. He maintained this routine for the next quarter of a century, repeatedly returning to New Orleans and again accepting work in the North.

An Itinerant Musician

A chronological overview of the bands and musicians Barbarin worked with in the course of his career indicates the breadth of his musical contributions: Before he left for Chicago in 1917 he was with the Silver Leaf Orchestra, Buddy Petit and Jimmie Noone, Chris Kelly, Sidney Bechet, Emanuel Perez, and the famed Onward Band. In Chicago he accompanied Edith Wilson and Clarence Johnson; played with Joe “King” Oliver in Bill Johnson’s band, Freddie Keppard, Emanuel Perez, and Jimmie Noone; and toured with the Tennessee Ten and his own trio.

In 1922–1924, back in New Orleans, Barbarin worked with Punch Miller; the Onward, Excelsior, and Tuxedo brass bands; and the band at Tom Anderson’s Café led by Luis Russell, Albert Nicholas, and finally himself. In 1924 he joined Russell, Nicholas, and Barney Bigard in Chicago and later New York City as members of King Oliver’s Dixie Syncopators. He participated in a number of classic recordings during this time. In 1927, during a brief residence back in New Orleans, he worked in the bands of Fats Pichon and Armand Piron. Barbarin returned to New York the same year to join Russell’s new band with Red Allen, producing seminal recordings. After three years he left the band to work with Pichon, Jelly Roll Morton, and his own band. In the early 1930s Barbarin returned to New Orleans for two years and formed his Jump Rhythm Boys. In 1934, having returned to New York, he rejoined the Russell band, which in 1935 became the Louis Armstrong Orchestra. In 1938 Barbarin went back to New Orleans, where he joined Joe Robichaux’s N.O. Rhythm Boys, then Walter Pichon and the Red Allen Sextet. He toured the Midwest and California with the latter group in 1942, followed by a residency with Sidney Bechet.

Barbarin returned to New Orleans—this time permanently—in 1944 and worked with a variety of name bands around town, such as Sidney Desvigne’s Southern Jazz Kings, the Joe Robichaux and Joe Phillips Orchestras, to name but a few. He formed his own New Orleans Jazz Band in 1949. This band played in the old style and became one of the most popular in the city, with regular work on Bourbon Street and elsewhere. Barbarin was also a member of the Young Tuxedo and Olympia brass bands. In 1960 he reformed the Onward Brass Band with Louis Cottrell, both sons of the band’s original nineteenth-century members. In 1969, on a Mardi Gras parade with this band, Barbarin collapsed and died.

Influenced by Brass Band Tradition

Barbarin was a largely self-taught drummer, although he perfected his reading abilities while with Luis Russell. From his early years he particularly admired Jean “Ratty,” Louis Cottrell Sr., “Lil’ Mack” Lacey, James “Red Happy” Bolton, Ernest “Nini” Trepagnier, and Dave Bailey. In spite of his musical versatility Barbarin retained subtle elements of the New Orleans brass band tradition in his playing. His style rests fundamentally on the synthesis of snare and bass drum, adding cymbal beats for emphasis and the tom-tom as an extension of the role of the bass drum. His rare solos are strongly reminiscent of a brass band bass-and-snare drum solo passage, with the same mesmerizing, funky beat and joyful abandon.

Barbarin’s ensemble playing is not only an object lesson in clarity and functionality, but also a history lesson on drumming styles at the beginning of the twentieth century. This is true even in his work with the swing bands of Luis Russell, Louis Armstrong, and Red Allen, although he had adopted the four-beats-to-the-bar rhythm that was generally preferred by that time. In spite of Armstrong’s respect for Barbarin’s perfect timekeeping, swing feel, and seemingly telepathic anticipation of a soloist’s phrasing, Barbarin was replaced by Sidney Catlett, an artist of the next generation who, although he owed much to New Orleans drumming (Zutty Singleton was an early mentor), represented a lighter, more modern and dynamic approach to jazz drumming. Barbarin’s later career, back in his hometown, reestablished him as a pioneer and leading representative of classic New Orleans drumming.

Barbarin was a consummate businessman who kept himself and his band in work over the years, both in New Orleans and on tour in the United States. In the early 1950s he became the first New Orleans (and first black) endorser of Britain’s Premier Drum Company. He was also the composer of many songs, including the popular standard “Bourbon Street Parade” in 1954. He was unable, however, to match the international popularity of the George Lewis band in the 1950s and 1960s, possibly because of his insistence on the older two-beat style, in contrast with Lewis’s four beats to the bar. Barbarin influenced many New Orleans drummers, including Freddie Kohlman and Chester Jones. Barbarin’s recordings, spanning over forty years, form an important documentation of early New Orleans jazz drumming.