Prohibition

Louisiana reluctantly became subject to prohibition, the effort to eliminate alcoholic drinks, as a result of the 1920 federal law commonly known as the Volstead Act.

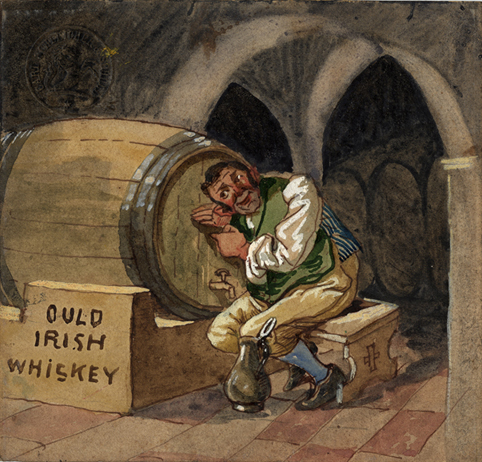

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

Ould (sic) Irish Whiskey. Bohunek, Rudolf (Artist)

In the early twentieth century, Louisiana reluctantly became subject to the abolition, or prohibition, of alcoholic drinks as a result of the federal law. The ban on alcohol mandated by the 18th amendment to the US Constitution, commonly known as the Volstead Act, was approved by Congress in December 1917, ratified with the approval of thirty-six of the forty-eight states in January 1919, and became law on January 16, 1920.

The effort to eliminate alcohol, or the “dry” movement, as it was often known, actually began in earnest in the 1840s. In 1869 an official Prohibition Party emerged to coordinate dry efforts. By 1873 the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) eclipsed other national antialcohol movements, emerging as a potent political force across much of the South and Midwest. The Louisiana branch of the WCTU boasted a large membership of politically active “drys.” During the Progressive era (1890–-1920), the Anti-Saloon League established itself as an umbrella organization to coordinate prohibition efforts.

Attitudes about Prohibition

Louisiana proved an uneasy partner in the “noble experiment.” Much of north central Louisiana, portions of the Florida Parishes, the Black Belt parishes along the Mississippi River, and the western Sabine River parishes were dominated by strongly pro-prohibition Baptist and Methodist adherents. Yet the majority of Louisiana residents opposed the prohibition of alcohol. Many Roman Catholics, Episcopalians, and German Lutherans across the southern part of the state intensely resisted the new law. Business interests in New Orleans and other southern Louisiana urban areas also opposed prohibition due to the economic implications it entailed. Many “wets” enjoyed the opportunity to consume alcohol, while others resisted the law in the belief that government had no right to legislate morality.

Unlike some states that exhibited near homogeneity in their stance on drinking hard liquor, Louisiana endured deeply entrenched divisions. Many residents accepted prohibition arguments that alcohol contributed to moral depravity and illicit behavior. Others believed it advanced the misery and debauchery of the poor, especially among newly freed African Americans. Still others claimed alcohol served as a root cause of Louisiana’s exceptionally high rates of violence. Yet, alcohol had always played a prominent role in Louisiana life. Whether celebrating Mardi Gras, joining in a corn shucking, or enjoying an elegant meal at a New Orleans restaurant, alcoholic drinks proved a normal concomitant to Louisiana culture.

Prohibition Takes Effect

When the law took effect in January 1920, Louisianans quickly perfected numerous methods to circumvent it. Indeed, some have argued that drinking liquor became even more popular in Louisiana after it was declared illegal. Rumrunning became a major industry; smugglers brought so many shiploads of illegal liquor to Louisiana that the price actually began to decline. A 1926 survey of social workers nationwide identified New Orleans as the “wettest” city in America. A similar 1924 report issued by the US Attorney General’s office declared southern Louisiana to be 90 percent wet. In rural upstate parishes, illicit stills concealed in the vast woodlands provided customers with prodigious quantities of moonshine liquor, ranging from “Blind Tiger” to “Busthead” whiskey.

The political atmosphere of the state facilitated Louisianans’ ability to resist prohibition. Some members of the New Orleans city council sought to have alcohol declared a food supplement in order to circumvent the law. When asked by the mayor of Atlanta what his administration was doing to enforce prohibition, Louisiana governor Huey P. Long famously responded “not a damn thing.” Scores of Louisiana residents, whether they consumed alcohol or not, simply resented the intrusion of government into what they perceived as private affairs. Thus, they refused to support enforcement of the law.

Despite such obstacles, federal agents worked aggressively to enforce their mandate. Coast Guard cutters stepped up interdiction of rumrunning throughout the 1920s, even firing on and sinking some runners such as the Canadian-registered schooner, I’m Alone, in the Gulf of Mexico. Liquor raids peaked in New Orleans in 1925 when 200 agents uncovered and destroyed more than 10,000 cases of liquor. By December 1926, New Orleans had more padlocked speakeasies or saloons illegally selling alcohol than any city in the nation. When repeal of the prohibition law occurred in April 1933, more than nine hundred retail beer permits were issued in the Crescent City in the first week.

In Louisiana, as elsewhere, prohibition did reduce the overt consumption of alcohol. Yet it also contributed to social degradation by promoting multiple forms of criminal behavior such as rumrunning, moonshining, and violent turf wars, not to mention increasing hostility toward government agents and the legal authority they represented. In the end, prohibition may have been a noble experiment, but its legacy was short lived in Louisiana. As recently as the 1980s, the Louisiana legislature proved willing to temporarily forgo federal highway construction appropriations rather than raise the drinking age to twenty-one. Consuming alcoholic beverages has proven a deeply ingrained dynamic of Louisiana culture that even the federal government cannot mitigate.