Red River Campaign

In the 1864 Red River Campaign, Union troops attempted but failed to surround Confederate forces in northwestern Louisiana.

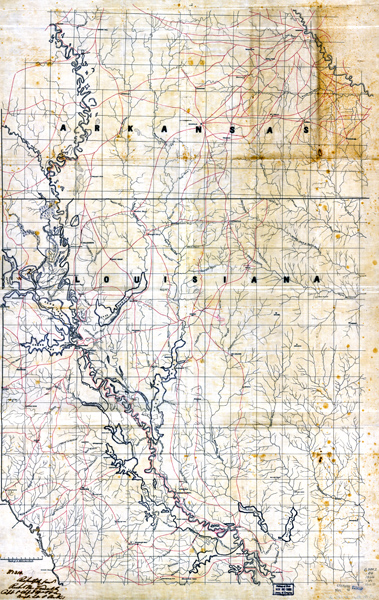

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Color reproduction of an 1864 map of the Red River Campaign of the Civil War by Richard M. Venable.

When pressed for his opinion about the Union’s ill-fated spring 1864 Red River Campaign into northwest Louisiana, Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman called it “one damn blunder from beginning to end.” It is an assessment still shared by many historians today. What had begun as an ambitious and confident conquest of the Red River Valley ended in ignominious defeat. Yet the blunders that characterized the campaign were not confined to the Union. A lack of coordination among the Confederate defenders prevented them from capitalizing upon their hard-fought gains. As such, the Red River Campaign was perhaps an even larger missed opportunity for the Confederacy than it was a disaster for the Union.

Planning the Campaign

Until the start of 1864, the Union had enjoyed considerable success in Louisiana. New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and much of Acadiana lay in federal hands, and with the surrender of Port Hudson in July 1863, the Mississippi River was also under complete Union control. Yet the northwest portion of the state, including the Red River Valley, remained in Confederate hands. Though the Union had severed transportation routes from the Red River to Confederate armies in the east, the region continued to provide sustenance and income for the flagging southern war effort in the west. The defense of this vast area fell to the Army of the Trans-Mississippi commanded by General Edmund Kirby Smith, who made his headquarters at Shreveport. The presence of this still-formidable force threatened the stability in Union-held parishes, undermining the wartime political goal of President Lincoln to readmit a loyal congressional delegation from Louisiana.

Although some, such as General Ulysses S. Grant, doubted the necessity of marching on Shreveport, victory would bring tangible military and political gains. Situated strategically on the last high ground overlooking the Red River, Shreveport’s easy defense caused southern military planners to concentrate armaments manufacturing there. Moreover, it was home to a nascent naval yard that built both ironclad warships and unproven but feared submarines. With Baton Rouge in Union hands, Shreveport became the capital of Confederate Louisiana, and therefore an important political and military target. Also difficult to ignore in the strategic calculus were the enormous profits both the navy and civilian speculators might make in confiscating Confederate cotton in a region known for producing the staple in quantity. By the end of 1863, the price of cotton had hit new heights. Governed by traditional naval law, Union ships could seize bales of cotton as a prize, with a substantial portion going to the ships’ commanding officers. The army might seize it as contraband of war.

The Red River Campaign started at the confluence of the Red and Mississippi rivers and consisted of a two-pronged push toward Shreveport. The navy under Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter was to ascend the Red River, while the army under Major General Nathaniel P. Banks marched overland. Ideally, the two forces would provide logistical and tactical support to each other, but deep animosity between the two men eliminated any possibility of meaningful coordination.

Both the army and navy gathered formidable forces for the campaign. Banks’s army consisted of approximately 30,000 men, or from double to triple the number of Confederates he was to face. Even more disproportionate was the size of the naval squadron assembled by Porter, which included more than thirty warships of various tonnages and an even more numerous flotilla of support and transport craft.

The terrain of the Red River Valley played an important role in the outcome of the Union’s combined offensive against Shreveport. The antebellum activities of ambitious frontiersmen had transformed the landscape of this watershed, and few were more important than Captain Henry Miller Shreve, the town’s namesake. For centuries, the Great Raft, a giant logjam, had clogged the Red River and caused it to overflow its banks, creating other rivers, lakes, and bayous. Shreve cleared the raft, and the Red River, with careful maintenance, flowed free to the Mississippi. The Union naval advance would soon discover, much to its dismay, the extent of local experience in manipulating the stream. Both the army and the navy also found that the multitude of waterways created by the raft made navigation difficult.

The Advance

The expedition officially began heading up the river on March 11, 1864, and it enjoyed some early successes. Fort DeRussy, an earthworks designed to hold the advance, fell quickly and by March 15, Union troops marched into Alexandria. It was here that both Banks and Porter made fateful and ultimately poor decisions. Porter, heeding rumors that powerful Confederate ironclads awaited his arrival upstream, decided to bring all of his ironclad vessels across the falls at Alexandria, including the 280-foot Eastport. The fact that the Red River’s level was falling at a time when it should be rising should have aroused greater caution in Porter. Meanwhile, Banks elected to march his army on a shorter, more inland route toward Shreveport, despite the fact that it took him far away from the powerful guns and logistical support of Porter’s fleet. Some historians speculate that Banks, a political general and former speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, had hoped that single handedly taking Shreveport might propel him into the presidency in 1864.

Banks’s inland route “through the howling wilderness” to Alexandria put his army on roads of red clay that rain made nearly impassable. The army’s long train was poorly organized, leaving it weakened and vulnerable. Moreover, Banks chose a route with few opportunities for forage. For miles on end, the roads were lined with nothing but thick pinewoods, whereas the river road was dotted with farms and ample forage. As a consequence, the column moved very slowly, and this allowed Banks’s Confederate counterpart, Major General Richard Taylor, to scout his location and enjoy the luxury of choosing the ground upon which he would give battle.

Confederate Victory at Mansfield

On April 8, 1864, Taylor decided to make his stand at a place known as the Sabine Crossroads, just south of the town of Mansfield in De Soto Parish. In 1864 the region was mostly pine forest, but this location on what locals called Honeycut Hill offered a wide clearing—an ideal location for the Confederates to establish a line of defense. Not wishing to reveal his numbers, which were less than half of those commanded by Banks, Taylor stationed his men along a nearly three-mile-long L-shaped front. The field of fire from both legs of this formation converged at the point where the road carrying the Union force entered the field. Taylor believed that Banks would blunder in and rashly attack the Confederate lines, a move that might have given Taylor the opportunity to trap Banks and achieve total victory. Yet Taylor had underestimated his counterpart’s ability for mismanagement, for at no point during the battle was the Union force so organized as to make it capable of making such a bold attack.

By the late afternoon, Taylor’s army decided it could no longer wait and took the offensive against Banks’s disorganized force. An uncoordinated attack made by the Confederate left led directly to the death of some of its commanders, including Brigadier General Alfred Mouton, the son of antebellum Louisiana governor Alexandre Mouton. Despite these early mistakes, the disposition and leadership of the Union force under Banks doomed the besieged Union force to defeat. The formidable supply train that had for days slowed the column’s advance now choked the narrow road. This situation not only prevented the timely arrival of reinforcements at the battle, but also made an effective and orderly retreat impossible. The loss at Mansfield fell squarely upon Banks, who failed to heed the advice of better-informed subordinates during the engagement.

The Retreat of the Union Army

Banks’s army was in full retreat by the evening of April 8, but Taylor’s Confederates could not pursue with the onset of darkness and the overall exhaustion of the army. Yet Taylor believed that he might yet fight a decisive battle the following day, which would effectively destroy Banks’s army. What he did not know was that the battle-tested Sixteenth Corps under A. J. Smith had not been part of the action at Mansfield and now stood in reserve with Banks’s army as it rested at the town of Pleasant Hill.

Taylor’s army found much more determined resistance when it attacked the following day, April 9, at Pleasant Hill, and these discouraging circumstances were exacerbated by the misinterpretation of orders by subordinates. Yet Banks’s leadership remained a liability. Having lost much of their supply train at Mansfield and running low on water, the Federals retreated from the field of battle toward Grand Ecore. Taylor had missed his opportunity to fully defeat Banks at the stalemate at Pleasant Hill, but it would not be his last chance to do so.

Believing that if he could muster a larger force he might finish off Banks, Taylor appealed to General Kirby Smith for more men. Instead, Smith took away three divisions for an attack in Arkansas against a Union column moving southward from Little Rock. Just as Banks and Porter had made fateful decisions at Alexandria, so, too, did Smith at Shreveport. By taking troops from Taylor and sending them on an unnecessary mission to Arkansas, he effectively eliminated any realistic hope of ultimate victory. Taylor was furious at this decision, and would never forgive Smith for making such a grievous mistake, driven as it was by personality conflicts.

Nevertheless, Taylor continued to attack Banks’s army as it retreated to Grand Ecore. At the battle of Monett’s Ferry on April 23, Taylor had the blundering Banks trapped on an “island” formed by the Cane and Red rivers. Only miscommunication among Taylor’s subordinates and inadequate numbers of Confederate attackers saved Banks and his army. By the end of April, 6,000 Confederate soldiers had managed to surround nearly 31,000 demoralized and poorly led Union troops at Alexandria.

Disaster for the Union Fleet

While Banks foundered in the wilderness, Porter proved no more able to reach Shreveport. What he did not know was that the Confederates had used an old man-made channel called Tones Bayou to divert the majority of the Red River’s flow. This meant that with every mile upstream, the river became increasingly difficult to navigate. Ultimately, the squadron reached a spot where the Confederates had scuttled the giant steamboat New Falls City crosswise in the river. The water was so low that both ends of the wreck extended onto dry land on either bank. Running out of navigable stream and learning of Banks’s defeat, Porter began a retrograde movement. The mighty Eastport became the first and perhaps most significant casualty, having run so hard aground that it had to be destroyed. Porter would lose several other support vessels to accidents and enemy shore fire in his inglorious retreat to Alexandria.

The navy was hardly in the clear when it reached Alexandria. The same falls that Porter had run almost two months earlier were now impassable. Only the engineering experience of an army officer, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey, saved the fleet. Bailey, who had logging experience in Wisconsin before the war, proposed and built a series of temporary dams that formed a chute through which the heavy ironclads might pass. By May 13, the imperiled force finally cleared the falls at Alexandria.

With the navy no longer in jeopardy, Banks was free to continue his retreat. Taylor’s diminished force could harass and continue inflicting casualties on the Union soldiers, but he lacked the manpower to stop and defeat them. Taylor made two last efforts to stop Banks at the Battle of Mansura on May 16 and at Yellow Bayou on May 18, but he could not prevent the Union army from retreating across the Atchafalaya River to safety.

Controversy and Blame

Porter, who had a heroic reputation up to this point, was somewhat tarnished by the Red River debacle. Banks, who had never displayed brilliance on the battlefield, was finished as an operational military commander. The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War investigated the campaign for nearly a year, only to conclude that it was a textbook model of how not to fight a war. The Confederate Congress offered a special message of thanks to Richard Taylor for his heroic leadership, but it was little consolation to the man who had hoped to drive the Yankees from his native Louisiana. On June 6, 1865 Shreveport became the last Confederate state capital to surrender to Union authority, nearly two months after Appomattox.