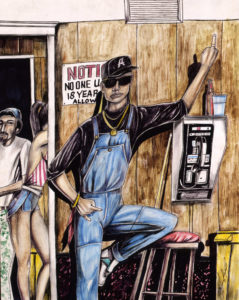

Roy Ferdinand

Artist Roy Ferdinand chronicled the street life and characters from some of New Orleans' toughest neighborhoods with graphic, head-on representations of his subjects.

Courtesy of Roger H. Ogden Collection

Streamline Lounge. Ferdinand, Roy (Artist)

For fifteen years, Roy Ferdinand chronicled the street life and characters from some of New Orleans’s toughest neighborhoods. He created an epic body of work—some two thousand drawings scattered among private collections, galleries, and museums across the country—documenting the distinct, and often troubled, culture of the city’s African American residents.

Although Ferdinand drew inspiration from events he witnessed, took part in, or saw in the pages of the local newspaper, his best work transcends time and place. Dark, sometimes bizarre subject matter can bring to mind Francisco Goya or Hieronymus Bosch: Thugs prey on the weak and kill each other; a homeless woman wrapped in an American flag wears cardboard for shoes; prostitutes display guns; a ragged man sitting on a back stoop skins a cat for dinner; an imp in a crack house grins at an act of bestiality. Parallels to his work among modern artists include the art of New York painter Leon Golub, who held that an artist must work from directly observable life to have political or social relevance and delved into such subjects as violence, power, sex, and politics.

Ferdinand’s limited palette and minimalist style is far from painterly, however. His near-journalistic presentations could be compared to the New Realist photographers of mid-twentieth century New York. The disturbing mix of pathos, anger, and whimsy in some of his portraits of New Orleans street kids is reminiscent of Diane Arbus’s Child with toy hand grenade in Central Park. His gunned-down drug dealers juxtaposed with street signs reading “Stop” and “One Way” recall a photo by Weegee (the pseudonym of photographer Arthur Fellig) of a corpse under a movie marquee reading Joy for the Living. Like the neorealists, he approached his subjects head-on, with flat compositions that often lack depth of field. But Ferdinand worked with his memory and imagination instead of a camera, using pens, pencils, markers, and small sets of watercolors on poster boards that he bought at local drug stores.

Ferdinand balanced his exploration of New Orleans’s violent subculture of gangs, guns, drugs, and crime—what he called “the black urban warrior myth”—with neighborhood portraits, some of which clearly seem to have worked as emotional outlets for the artist. He exhibited a natural gift for revealing emotion and character with a few pencil strokes. Elsewhere, his draftsmanlike skills and native intimacy with the hidden backyards and empty streets of the city create a charged atmosphere—danger and beauty are both at hand in his blue skies, boarded-up houses, and white cemetery crypts.

Yet Ferdinand’s formal skills are nearly always imperfect—misrepresentations add power and depth to his art. Bodies slightly out of proportion, multiple vanishing points, and tilted buildings become evocative characterizations of a subject—New Orleans—that is innately skewed and often morally off center. Graffiti is a recurrent motif, which Ferdinand often personalized by using the names of people he knew who had been killed on the street.

Much of Ferdinand’s work has a noirish or even Gothic sensibility, often seeming to involve his own search for monsters, both within and without. An obsessive fan of science-fiction and horror films, he often used horror as a metaphor. The drawings he left behind stand as a singular vision, a body of work that turns the mean streets of New Orleans into art, by turns sweet, sardonic, tragic, bizarre, and horrific. Ferdinand died of cancer on December 3, 2004.