Samuel Blessing

Of the hundreds of photographers in New Orleans during the second half of the nineteenth century, Samuel T. Blessing stands out for his longevity, production, and business acumen.

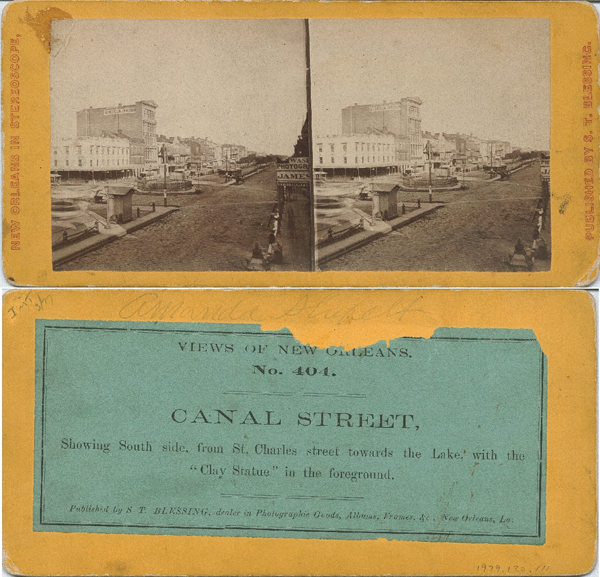

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Canal Street. Blessing, Samuel T. (photographer)

Of the hundreds of photographers in New Orleans during the second half of the nineteenth century, Samuel T. Blessing stands out for his longevity, production, and business acumen. He entered the field as the first great wave of mass-market photography began, working as both a studio portraitist and dealer in stock images. Always aware of the latest technological innovations in the field, Blessing played a key role in the development of New Orleans photography. His influential gallery/studio—which also sold photographic supplies and equipment—served as a valuable resource for many of New Orleans’s early amateur and professional photographers.

Born in Frederick, Maryland, on March 19, 1830, Samuel Tobias Blessing was the son of John Blessing and Anna Brown Blessing. Historian Frances Robb documents Blessing in Alabama (Tuscaloosa in 1854 and Greenville the following year), and Palmquist and Kailbourn have him established in La Grange, Texas, in 1856, before he arrived in Louisiana in December of that year.

His photography career in New Orleans began in 1856, when he entered a partnership with Samuel Anderson. Along with their New Orleans photography studio, the pair simultaneously operated a studio in Galveston, Texas, until about 1860. The 1850s saw the introduction of the wet-plate process (making it easier to produce detailed prints); the arrival of the stereographic photograph (the viewing of which became a popular pastime); and the launch of the carte-de-visite (or calling card) photograph, which could be produced in unprecedented quantities and distributed far and wide. Blessing availed himself of these new technologies (along with the fading ones of daguerreotype, ambrotype, and tintype) and others that arrived with the march of photographic technology during the later decades of the century.

In 1863, Blessing and Anderson dissolved their partnership, and Blessing operated under his own name for the remainder of his career. Around the same time, his interest shifted from creating studio portraits to publishing and dealing in photographic stock images. Arguably the most important groups of photographs he published are three stereograph series entitled New Orleans in Stereoscope, Views of New Orleans & Vicinity, and Public Buildings in New Orleans from 1866. The collective nature of these series, portraying cityscapes, individual architectural subjects, and the Louisiana countryside near New Orleans, offers an unparalleled visual record of the region during the Reconstruction era and beyond.

Both before and after the Civil War, Samuel Blessing’s brothers—John P. and Solomon T. —operated photographic studios in Houston, Galveston, and Dallas, Texas. The Dallas operation, begun 1886–87, appears to have been in partnership with Samuel.

Throughout his career, Blessing’s studio and gallery—which sold photographs, prints, other artworks, and frames along with supplies for the amateur trade—was located in the thick of the commercial district, on or near Canal Street, where many photographic businesses were centered. His four-story building at Canal near Chartres Street was heralded as one of the finest photographic emporiums in the South. As cameras became smaller and lighter, and as flexible film was introduced as an alternative to glass plates in the late 1880s, camera clubs geared to hobbyists and dilettantes sprouted throughout the country. Professionals were often in the ranks of these groups, too, and Blessing was listed as an honorary member of the New Orleans Camera Club in 1891.

Contemporary references state that after a two-year unspecified and painful illness, Blessing died November 18, 1897, in St. Louis, Missouri, where he had gone earlier in the year to recuperate. At his request, notices of his passing in the New Orleans papers were minimal. He was interred in Lafayette Cemetery, Number 1, in New Orleans. The ascendant curve of photographic technology during the medium’s first half-century catapulted some practitioners to new heights, while shunting aside others to footnotes of history. Samuel T. Blessing clearly lies in the former group, as evidenced by his pictures and his competence as both a photographer and businessman.