Shirley Rabé Masinter

Artist Shirley Rabé Masinter has gained considerable attention for her rich oil and watercolor depictions of the gritty streets of Louisiana's inner-city neighborhoods, cemeteries, and landscapes.

Courtesy of LeMieux Galleries.

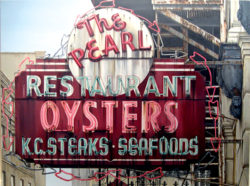

Artist Shirley Rabé Masinter's 2003 oil painting "The Pearl" is a faithful depiction of the New Orleans' restaurant's neon sign.

Artist Shirley Rabé Masinter has gained considerable attention for her rich oil and watercolor depictions of Louisiana landscapes and the gritty streets and cemeteries of New Orleans. Masinter uses the intensity of midday sunlight to create stark lighting contrasts in her graffiti-filled inner-city street scenes, rural landscapes, or among the crumbling tombs in New Orleans’ still-functional colonial cemeteries. With extraordinary drawing talents and a great deal of patience, perhaps tempered by her long career as a commercial artist for the now defunct D.H. Holmes department store, Masinter meticulously records in her paintings every crack in the sidewalk, every leaf in a tree, or every fern growing from cracked plaster in an ancient mausoleum. She captures the dried rivulets of rust in the marquees from shuttered theaters and restaurants.

To Masinter, born in New Orleans on December 11, 1932, the city itself has an intensity and vibrancy that drive her work. Since the 1990, two major aspects of New Orleans have captured her attention — the city’s historic burial grounds, known as Cities of the Dead, and poor, decaying inner-city neighborhoods. “I’ve never really thought about it,” she said of her choice of subject matter. “I just see a certain beauty in it. Maybe it’s because I grew up in an old neighborhood. I drive through a rundown section of the city and say, ‘Wow! Isn’t that beautiful.’ Maybe these old neighborhoods show more character. Though some of the old buildings and houses are abandoned, they somehow show life, that someone once lived there.”

In paintings such as New and Used Furniture (2010) and Shamrock Tavern (2010), Masinter says she focuses “on a city in transition with many controversial and dynamic social forces at play. These works are not literal ‘slices of life’ captured at random on the city streets; instead, each is a synthesis or construction that gives my representation of the places depicted.”

Art critics describe Masinter’s painting style as hyperrealism rather than photorealism in the way Richard Estes and others made the style popular in the late 1960s and 1970s. “Photorealists strictly work from the photographs they shoot,” Masinter said. “They make a few adjustments, because the camera distorts the image somewhat, but they don’t change backgrounds. I create my paintings by bringing in various elements of what I see.” Unlike Photorealists, she photographs and collects pieces of imagery from around the city and then builds a composite around a central image.

Earlier in her career, Masinter, like most seasoned artists, sat on location and sketched the scene in pencil and made a few color notes for later reference back in the studio. “Now, I take a lot of photographs,” she said, “but every now and then I do a drawing on location to see if I can still do it.” Back in the studio, these images come together as she draws from the hundreds of photographs she has taken of old advertising signs, political campaign posters, street lamps, people’s faces, decaying houses, graffiti-scarred walls, and anything else that grasps her imagination.

Some people have criticized her work as romanticized views of graffiti-blighted ghettos by a woman who does not live among such blight. “I think there is a lot of anger there,” she says, “but I hope my paintings will draw attention to the problems in a positive way. I also think many graffiti artists are frustrated artists.” Masinter has rarely encountered problems gathering photo images of neighborhoods and people for her paintings. “People are usually very nice,” she says. “If I’m sketching in a neighborhood, people come up to me and ask what I’m doing. Most people are wonderful and cooperative.”

Masinter says she paints “to express visually things that excite me, interest me, or feelings that I want to convey to other people in a positive way, even though they may be buildings with some decay. I think there’s a feeling of home in my work, and I don’t think it makes any difference whether you’re black, white or Indian. Georgia O’Keefe did some beautiful Southwest paintings and she certainly wasn’t a Navajo. She was trained in New York.”

Like many other notable New Orleans artists, including Henry Casselli, Rolland Golden, and Alan Flattmann, Masinter was a student of the acclaimed John McCrady School of Art in the French Quarter, led by its namesake southern regionalist painter. She received a BFA from Tulane University and later an MFA from Newcomb College. She has participated in numerous juried art shows, and her paintings can be found in the following public collections: the New Orleans Museum of Art; the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans; the Mississippi Museum of Art in Jackson; the Huntsville Museum of Art in Alabama; and the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia.