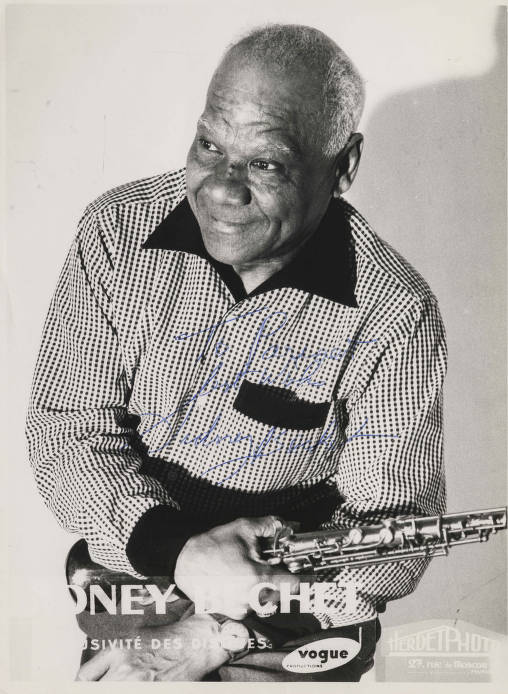

Sidney Bechet

Clarinetist and soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet was one of the first great soloists of traditional New Orleans jazz.

Courtesy of Louisiana State Museum

Sidney Bechet. Unidentified

Clarinetist and soprano saxophonist Sidney Bechet was one of the first great soloists of traditional New Orleans jazz. Renowned for his lyrical, swinging phrases, emotional blues sensibility, and ample use of vibrato, Bechet continues to exert vast influence on the traditional jazz scene in New Orleans and elsewhere. He is especially lionized in his adopted homeland of France.

Born in New Orleans on May 14, 1897, Bechet grew up in a middle-class Creole family who preferred mainstream European music to the African-Caribbean sounds that were then evolving into jazz. The latter was often dismissed as low-class, underscoring a common dichotomy within the New Orleans black community at the time. “Us Creole musicians,” Bechet’s older brother Leonard stated, “always did hold up a nice prestige.” Even so, Bechet’s family was very supportive of his budding talent, which became apparent at an early age. One childhood incident is especially instructive. When Bechet was ten, his mother threw a birthday party and hired a band that included the great jazz cornetist Freddy Keppard. The band also featured a respected clarinetist named George Baquet, who arrived late. Sidney, too shy to perform in public, played along from another room, and everyone assumed they were hearing Baquet, the adult professional. Baquet was soon giving Bechet lessons, as were other prominent figures, including Lorenzo Tio, Jr., and Louis “Big Eye” Nelson. Although an avid pupil, Bechet was resistant to formal training.

As an adolescent, Sidney Bechet began performing in public with his brothers’ Silver Bell Band. Next he joined the Young Olympians, a venerable outfit that is still active at this writing, and then moved on, yet again, to play with cornetist Bunk Johnson in the Eagle Band, a group once led by Buddy Bolden. Soon Bechet was working with Clarence Williams, a Louisiana pianist/composer/entrepreneur whose work encompassed blues, ragtime, early jazz, and show tunes. Williams took the teenaged Bechet on a tour that eventually led to a European tour in 1919 with violinist and composer Will Marion Cook. Bechet’s masterful, articulate improvisations were praised by the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet, who called him “an extraordinary clarinet virtuoso” and praised his “extremely difficult” solos for their “richness of invention, force of accent, and daring in their novelty and the unexpected.” This was a remarkable endorsement at a time when jazz was largely scorned in classical music circles.

Bechet returned to America and in 1923 recorded with Clarence Williams’s Blue Five, a band that also included Louis Armstrong on a 1924 session. During this period, Bechet also worked briefly with Duke Ellington’s orchestra. He then went back to Europe, building a reputation as an accomplished musician with a wild personality. Jailed in Paris after a shooting incident, Bechet was deported from France in 1929. He went to Berlin and appeared in the musical film Einbrecher. Returning to the United States, Bechet began working with bandleader Noble Sissle, of Shuffle Along fame, in 1930.

During much of the 1930s, Bechet based himself in New York. He formed a band called The New Orleans Feet-Warmers that featured another Crescent City expatriate, trumpeter Tommy Ladnier. The group’s inspired recordings included “Shag” and “Shake It and Break It,” although none sold especially well. Bechet and Ladnier also worked, for a time, with Noble Sissle. When gigs became sparse, the two became partners in a tailoring business.

In 1938 Bechet scored a hit with an interpretation of “Summertime.” In 1941, he made one of the first overdubbed recordings when he played the clarinet, soprano saxophone, tenor saxophone, piano, bass, and drums on a rendition of “The Sheik of Araby.” The late forties saw a revival of interest in traditional New Orleans jazz, especially in Europe. Smoothing over his old legal difficulties, Bechet began performing again in France with increasing frequency. He was received as a cultural icon and an elder statesman of jazz; by the early 1950s Bechet was a French resident. Perhaps his best-known recording from this era was a reworking of the old Creole song “Les Oignons.”

Despite flagging health, Bechet performed and recorded tirelessly in France. He also gave a series of extensive oral history interviews to journalist Joan Reid. Transcripts of these conversations and subsequent interviews by Desmond Flower and John Ciardi were edited by the latter two into the compelling autobiography, Treat It Gentle. The book was published following Bechet’s death on May 14, 1959.

As with Louis Armstrong and other traditional jazz musicians, Sidney Bechet’s music was out of vogue for some time, but it has enjoyed a well-deserved renaissance. At this writing his legacy is preserved by clarinetists such as his former student Bob Wilber and New Orleans clarinetists who include Dr. Michael White, Tim Laughlin, and Evan Christopher.