German Coast Slave Insurrection of 1811

As many as five hundred enslaved people participated in an uprising against slaveholders in the Territory of Orleans.

This entry is 7th Grade level View Full Entry

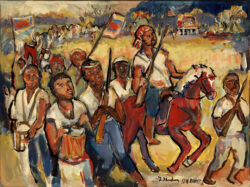

Courtesy of the Historic New Orleans Collection

1811 Revolt by Lorraine P. Gendron, 2000.

What is the context of the German Coast Slave Rebellion of 1811?

In 1811 enslaved people from Louisiana sugar plantations along the German Coast organized the largest slave rebellion in United States history. The German Coast was named after the large number of German immigrants who moved to the area in the 18th century. The area included St. John the Baptist and St. Charles Parishes. This area had the highest density of enslaved people in the Louisiana territory. The German Coast Slave Rebellion of 1811 occurred one year before Louisiana became a state.

How did the rebellion start?

The rebellion began on the evening of January 8, 1811, in the Territory of Orleans. Sugar planter Manuel Andry owned more than eighty enslaved men, women, and children, more than any other slaveholder in St. John the Baptist Parish. Enslaved people on his plantation went into Andry’s house and attacked him. Although severely wounded, Andry managed to escape the attackers and make it across the Mississippi River to the west bank. His youngest son Gilbert Thomassin Andry was killed in the attack, “ferociously murdered” in the words of his father.

After looting Andry’s plantation, the rebels traveled south on River Road, along the Mississippi River. Enslaved men and women joined the rebels as the group passed other plantations. Sometimes the rebels used force and intimidation to convince enslaved people to join them, but many more joined of their own free will. The group crossed into St. Charles Parish and headed for New Orleans, which was about thirty miles away. According to eyewitnesses, they beat drums, waved flags, and carried a variety of weapons, including firearms. The number of people rebelling varied, with eyewitness estimates ranging from 150 to 500 people. The rebels raided several other plantations and killed enslaver Jean François Trépagnier in St. Charles Parish. Trépagnier had attempted to defend his family’s plantation with a shotgun.

How did white residents react to the rebellion?

White residents, warned of the approaching rebels, looked for safety in New Orleans. William C. C. Claiborne, the governor of the Louisiana territory, ordered a lockdown and a curfew. General Wade Hampton, commander of federal troops, took command of a quickly formed force of troops, militia, and volunteers. The incident was the first time in US history that federal troops were used to stop a slave rebellion. Hampton ordered Major Homer Virgil Milton in Baton Rouge to move downriver from the north with more troops. Manuel Andry, despite his wounds, also rallied a militia force on the west bank of the river.

These three forces met on the morning of January 10. A unit of Hampton’s forces made first contact with the rebels shortly after they crossed into Orleans Parish. The main body of rebels was caught off guard by Andry’s militia at Bernard Bernoudi’s sugar plantation in St. Charles Parish. Militiamen, including some free men of color, charged the rebels, who were quickly defeated. The wounded Andry reported to Governor Claiborne that the fight was un grand carnage, or “a great slaughter.”

Judges, who were themselves wealthy slaveowners, assembled in St. John the Baptist Parish, St. Charles Parish, and New Orleans to hold trials of the enslaved people who took part in the rebellion. The alleged ringleader of the rebellion was an enslaved man named Charles Deslondes. Angry white residents captured Deslondes and shot, burned, and mutilated him. White residents of New Orleans who had experienced the Haitian Revolution were especially fearful of future rebellions. White residents placed the heads of enslaved people who had participated in the rebellion on poles. The poles were placed along the levee for more than thirty miles from Andry’s plantation to the gates of New Orleans, serving as a warning to other enslaved people.

The German Coast Rebellion of 1811 was the deadliest slave rebellion in US history. Close to one hundred enslaved men and women died in combat or by execution. The 1739 Stono Rebellion in colonial South Carolina and the 1791 Pointe Coupée Conspiracy in Spanish Louisiana were led by people from a single African ethnic group. The German Coast Slave Rebellion of 1811 was different. It included enslaved people from different ethnic backgrounds; men and women; field hands and more privileged slaves; and people of mixed African and European descent. Charles Deslondes was of African and European descent. He worked for Manuel Andry as a slave driver but was not owned by him. Andry’s neighbor owned him and hired him out to Andry.

What were the causes and goals of the rebellion?

There is little evidence that can help historians understand the exact causes and goals of the rebellion. Some participants of the rebellion had specific complaints about poor or violent treatment they received from their owners. The intense, brutal process of sugar production on plantations undoubtedly contributed to the rebellion. The rebels included mostly young, skilled enslaved men. It is most likely that the rebels meant to attack New Orleans. It is also possible that they meant to go to Haiti, where enslaved people had successfully rebelled against their enslavers and established an independent republic in 1804. But without a doubt, the most immediate goal of those who rebelled was freedom.