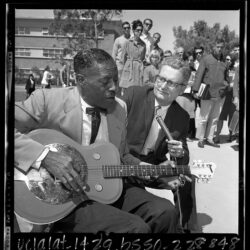

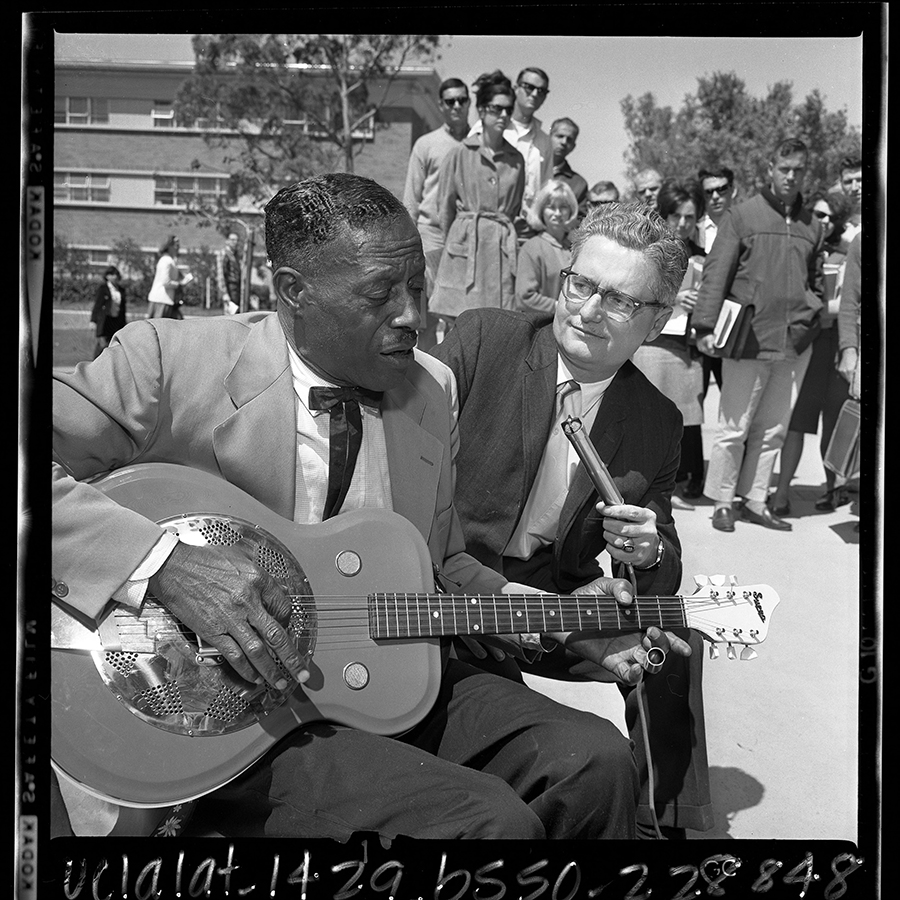

Son House

The guitar style of Edward James “Son” House has influenced blues musicians since the 1930s.

Univeristy of California Los Angeles Library Special Collections

Blues guitarist Son House playing at the University of California Los Angeles Folk Festival, May 13, 1965.

Decades after his passing, Edward James “Son” House remains revered as an important figure in the evolution of blues music. House is primarily renowned for playing slide guitar, also known as bottleneck guitar. This technique entails sliding an object—the sawed-off neck of a bottle, for example, hence the name—up and down the strings along the fretboard of a guitar. Doing so creates a glissando effect and can touch on notes at minute incremental intervals that are much smaller than those used in standardized musical notation. In addition, such notes may not conform with conventional standards of tuning and perfect pitch, existing instead, to use bandstand parlance, “in the cracks.” These effects, which invite comparisons to the nuances of the human voice, fit well with the deeply emotive aesthetics of blues music. So did House’s intense, impassioned singing.

Son House did not invent bottleneck guitar playing, but he excelled at it, significantly influencing younger African American blues guitarists such as Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters (born McKinley Morganfield). Their guitar work, in turn, greatly influenced—and, in the case of Muddy Waters, personally contributed to—the electrified blues sounds of the ‘50s, especially as played in Chicago. These amplified stylings subsequently inspired white rock guitarists—from the ‘60s through to this writing, in July of 2023—such as Eric Clapton, Duane Allman, Bonnie Raitt, and the contemporary duo Larkin Poe (Rebecca Lovell and Megan Lovell).

Slide guitar has long been an important component in the style known as Mississippi Delta blues. (The area known as Mississippi Delta is a tri-state region comprised of northwestern Mississippi, northeastern Louisiana, and eastern Arkansas, bisected by the Mississippi River. In this usage, the term “delta” is a geologically inaccurate descriptor for what, using scientific nomenclature, is an alluvial, or flood, plain.) Son House was born in the rural hamlet of Lyons, Mississippi, near Clarksdale in 1902. When his parents separated, House’s mother relocated the family across the Mississippi River to Tallulah, Louisiana, in Madison Parish, and then to New Orleans, settling in the Algiers neighborhood. At nineteen House married a woman from New Orleans and moved to her family’s farm near Centerville, Louisiana, in St. Mary Parish, where he worked as a laborer. During these years House played religious material only; like many musicians in a wide variety of genres, he shunned secular material as “the devil’s music.”

Upon moving back to the Mississippi Delta at age twenty-five, however, House took up blues, although he felt conflicted about doing so. He played at times with the guitarist Charley Patton, an iconic progenitor of Delta blues. In 1929 Patton had recorded for Paramount, one of the first labels to record rural acoustic blues as well as other indigenous forms such as Cajun music, Mexican-American music, and country music. In 1930 Patton brought House to a session for Paramount held in Grafton, Wisconsin. House played on some of Patton’s recordings and also recorded nine songs under his own name, for release in the 78 rpm format. House’s performances on these records were strong but sales were low. In 1941 and 1942 the folklorist Alan Lomax, the son of John Lomax, recorded House for the Library of Congress on field trips where he also made the first recordings of Muddy Waters. In 1943—reflecting the ongoing mass migration of southern Black people to northern industrial cities—Son House moved to Rochester, New York, where he set music aside for the next two decades and worked as a railroad porter.

In the early ‘60s a burgeoning folk-music revival triggered new interest in various older American genres and artists, including acoustic rural blues musicians of the ‘20s and ‘30s such as Son House. Young and predominately white aficionados and record collectors sought out these musicians, putting great effort in to trying to locate them and arranging for them to perform at events such as the Newport Folk Festival, primarily for white audiences. After Son House was “rediscovered” in 1964, to use the jargon of that day, he spent the next decade actively performing around the US and in Europe. He recorded prolifically, and his material from the ‘30s and ‘40s was reissued.

House gave many interviews to journalists during this era and, in addition to recounting his own life story, he often talked about Robert Johnson (1911–1938), whom he had taught to play. Johnson, House explained, at first did not play well at all, and he annoyed older musicians with requests to let him join them on the bandstand. Then Johnson went away somewhere for several months and returned as a virtuoso, much to the astonishment of House and his colleagues. “He [Johnson] sold his soul to the devil to get to play like that,” House told the noted blues journalist and researcher Pete Welding. House’s remark may have been fanciful or jocular; other people who knew Johnson dismissed it as absurd. But repetition turned House’s comment into a widely believed article of faith that created a posthumous image of Johnson—who was barely known when he recorded in the ‘30s—as a mythical, mysterious figure with purported occult connections. Today the state of Mississippi uses the story to promote music tourism. In their hyped telling of the tale, Robert Johnson specifically sold his soul to the devil at midnight, in Clarksdale, at the intersection of US 61 and US 49.

In a full-circle reprise of sorts, after having taught Robert Johnson, Son House likewise mentored a teenaged guitarist, John Mooney, in Rochester, some thirty-five years later. Mooney went on to move to New Orleans and gain worldwide acclaim as a slide guitarist with a vocal style that bears the distinct stamp of House’s singing. In 2024 Mooney recorded a tribute album entitled Son & Moon.

Failing health forced Son House to stop performing in 1974. He passed away in 1988.