Steel Magnolias

Steel Magnolias, a 1987 play by Robert Harling, centers on the bond among six southern women in the 1980s in the fictional setting of Chinquapin Parish, Louisiana and how they cope with the untimely death of a young mother within their tightly knit circle.

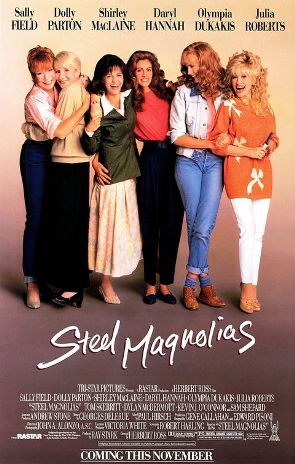

Wikimedia Commons.

A reproduction of the 1989 movie poster for Steel Magnolias.

Steel Magnolias, a 1987 play by Robert Harling, centers on the bond among six southern women in the 1980s in the fictional setting of Chinquapin Parish, Louisiana and how they cope with the untimely death of a young mother within their tightly knit circle. Harling’s work, with elements of tragedy and comedy, was inspired by the playwright’s hometown of Natchitoches and the death of his sister, Susan Harling Robinson, in 1985 due to complications from diabetes. The play’s title has become a metaphor for Southern femininity: a strong emotional core beneath a delicate-looking exterior. In 1989 Steel Magnolias was adapted into a movie under the direction of Herbert Ross; it was filmed on location in Natchitoches. A made-for-television version starring an all-African American cast was released in 2012.

A Story of Southern Women

On stage, the action takes place on a single set: a hairdresser’s salon known as Truvy’s Beauty Spot. The six characters include mother and daughter M’Lynn and Shelby Eatenton; Clairee Belcher and Ouiser Boudreaux, loudmouth grande dames of the small town; the wisecracking Truvy Jones; and her new mousy shop assistant, Annelle Dupuy.

The first scene opens with Annelle being hired just before the first Saturday morning clients arrive. Truvy explains that hers is “the most successful shop in town” because she believes in a strict philosophy: “There is no such thing as natural beauty.” She then adds, “Do not scrimp on anything. Feel free to use as much hair spray as you want.”

Clairee, widow of the former mayor, enters the shop as a shotgun fires in the distance. Shelby and her mother M’Lynn arrive, and the audience learns that it is Shelby’s wedding day and that the gunfire is Shelby’s father’s attempt to shoo away blackbirds from their yard, the site of the wedding reception.

In the midst of hairdressing and talk about the wedding, Shelby’s head drops down and the ladies spring into action. After getting a glass of orange juice and helping Shelby drink it, the ladies explain to Annelle that Shelby is a diabetic and has experienced an insulin-level spike. During the seizure, M’Lynn tells the women that Shelby’s doctor recently told her that she should not have children; Shelby suddenly blurts out that she and her husband-to-be could adopt, adding, “We’ll buy ’em if we have to.” When she regains her focus, she’s embarrassed, but the ladies appear composed, politely ignoring the previous commotion. Ouiser (pronounced “Weezer”) arrives soon thereafter, furious at M’Lynn’s husband for the racket he’s been making. The scene ends with Ouiser ordering her dog Rhett to attack him.

This opening scene underscores Harling’s brisk style as a playwright: by the time all six characters appear on stage—only about twenty pages in—the main plotlines and conflicts are established, and the tone has moved from light to dark and back again.

Six months later the ladies are getting ready for Christmas; the shop’s decorations include a tree that Annelle has festooned with hair clips, bows, and ribbons. She has given M’Lynn a pair of red plastic poinsettia earrings, her latest craft project. The ladies’ conversation is animated and amusing, but the scene ends with Shelby’s announcement that she is having a baby. She explains that she and her husband could “see the writing on the wall” after making numerous applications to adopt a child. Shelby’s medical condition would make a traditional adoption impossible. M’Lynn has gamely accepted the news, but her fear and worry are unmistakable to the other ladies. Shelby justifies her decision to defy doctor’s warnings and give birth by telling her mother, “I would rather have thirty minutes of wonderful than a lifetime of nothing special.”

Act Two is eighteen months later, and Shelby is getting her hair cut short as the other ladies enter the beauty shop. The audience learns that Shelby’s young son is doing well, but Shelby is not. The next day she is getting a kidney transplant, and her mother will be the donor. Her kidneys failed because of her pregnancy, and she has been undergoing dialysis for months.

The final scene occurs five months later; the banter among the ladies is light, but it quickly becomes clear that Shelby has died. When M’Lynn enters, the ladies keep up the patter, and it is Clairee, just back from a trip to Paris, who delicately inquires, “I’m beside myself. Wasn’t Shelby fine when I left? Can you talk about it?”

M’Lynn’s monologues are a balancing act as she tries to make sense of her daughter’s death. Harling uses Annelle as a comic foil during the scene, contrasting Annelle’s born-again Christianity (her latest interest) with M’Lynn’s motherly wisdom. M’Lynn declares, “I realized as a woman how lucky I was: I was there when this wonderful person drifted into my world, and I was there when she drifted out. It was the most precious moment of my life thus far.”

But M’Lynn’s frustration builds, and she finally admits that she “wants to hit something.” Clairee grabs Ouiser—who by now has established herself as the town’s crank— and exclaims, “Here! Hit this! Go ahead, slap her!” A few wickedly funny lines follow, with Clairee finally saying, “Things were getting entirely too serious there for a moment.” M’Lynn apologizes for making everyone cry, and Truvy responds with one of the play’s better-known lines: “Laughter through tears is my favorite emotion.”

On Stage and Screen

Critical response for the stage play was muted, but it ran for over two-and-a-half years at the off-Broadway Lucille Lortel Theatre in New York. Mel Gussow of the New York Times wrote: “Steel Magnolias is at its most perceptive in offhand moments, as when one woman [Annelle], caught up in her own problems, says, ‘I just can’t talk about it,’ and the others reflexively respond in unison, ‘Of course you can.’ Steel Magnolias is an amiable evening of sweet sympathies and small-town chatter.”

The film featured an all-star cast: Julia Roberts as Shelby, Sally Field as M’Lynn, Dolly Parton as Truvy, Olympia Dukakis as Clairee, Shirley MacLaine as Ouiser, and Darryl Hannah as Annelle. Harling’s screenplay remains relatively true to the original, except for the previously unseen male characters and numerous scenes filmed around Natchitoches. Despite lukewarm reviews—one critic called it “a small play made big by Hollywood”— the film did well at the box office. Released by Tri-Star Pictures on November 15, 1989, it ranked number four at the box office on its opening weekend and went on to gross more than $83.7 million worldwide. Roberts won a Golden Globe Award for Best Performance by an Actress in a Supporting Role in a Motion Picture and was nominated for an Oscar.

Lifetime Television Network produced a remake in 2012 under the direction of Kenny Leon, featuring African American actors in the lead roles: Queen Latifah as M’Lynn, Jill Scott as Truvy, Alfre Woodard as Ouiser, Phylicia Rashād as Clairee, Adepero Oduye as Annelle, and Condola Rashād as Shelby.

Harling claims that he wrote the first version of the play in only about ten days, doing his best to “capture exactly how those women spoke.” With Harling’s mother’s blessing, Steel Magnolias had its first production in February 1987. In a 2014 interview, Harling remembered his sister Susan as “a force to be reckoned with.” He added, “Desperate to be a mom, she defied doctors’ advice to have her much-wanted baby. She was a real-life force—just like the character of Shelby. She was just all the things that Shelby is—stubborn and wonderful.”