Students United

Students United was a student-led campus movement that advocated for student concerns at Southern University.

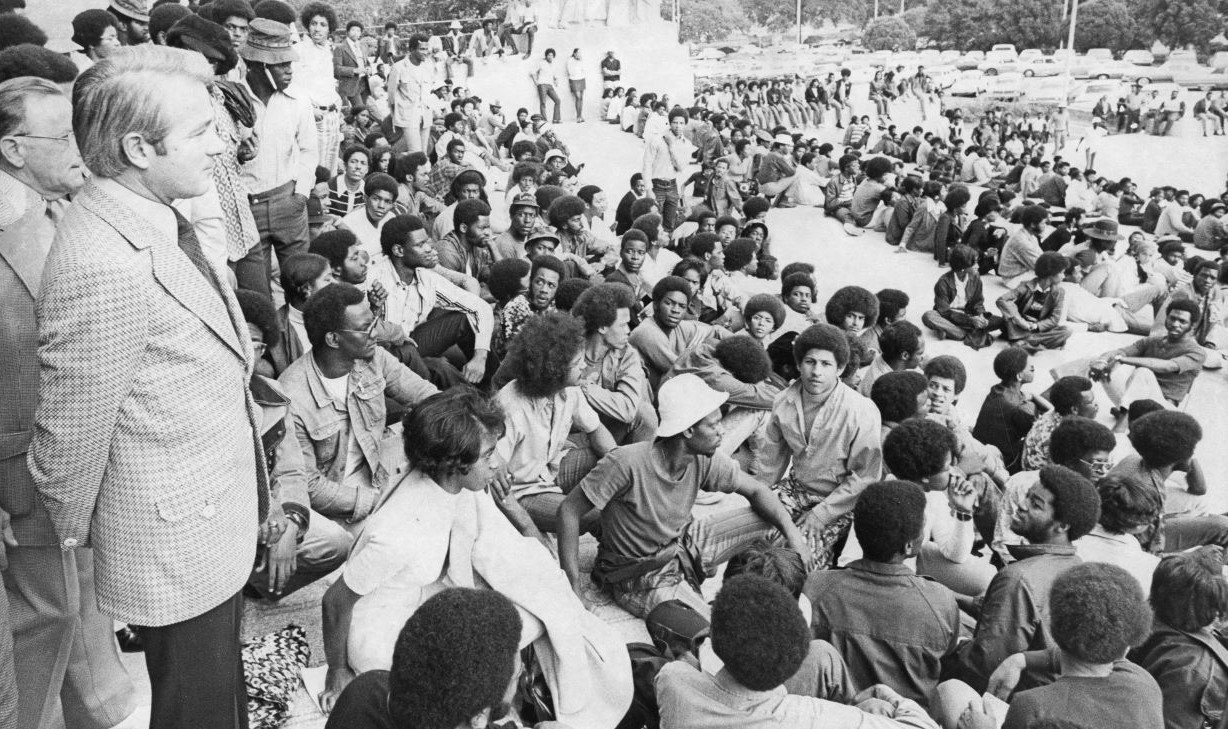

The Advocate / Capital City Press

Governor Edwin Edwards meets with members of the Students United movement over their protest of conditions at Southern University.

Students United was a student-led campus movement for change at Southern University in Baton Rouge, the main campus in a university system that had the largest number of Black students in the country at the time. Students United formed organically, drawing on the nonviolent civil rights movement. In 1960 four Black students staged a sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in North Carolina. The actions of the “Greensboro Four” inspired anti-segregation demonstrations across the South. In an effort to end segregation, college students on Louisiana campuses were routinely arrested throughout the 1960s. By the 1970s, when Students United formed, there had been years of agitation between Louisiana college students at Southern, Grambling University, and other campuses and local and state officials. Students United formed on the heels of the 1960s student movement, was informed by the 1972 Black Political Convention, and was invigorated by the return of students from service in the Vietnam War, where they had fought for the rights of others and returned expecting those same rights at home.

Formation

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs)—institutions of higher education founded prior to 1964 with the principal mission of educating Black students excluded from segregated public and private universities—have never received comparable funding with other institutions. HBCU presidents were typically accommodationists. They were tasked with maintaining harmony with students, who wanted mission loyalty, and, simultaneously, with winning the approval of state officials, who wanted political loyalty and social harmony, as defined by their constituents. This dynamic was in play at Southern during the lifespan of Students United.

In the 1970s students on Southern’s Baton Rouge campus were becoming increasingly disgruntled about worsening campus conditions and processes as well as their declining educational experience. Against this backdrop a dispute arose between a theater owner and Southern’s Psychology Club regarding underage children having access to mature content in the theater. The potential lack of access to the theater contributed to the feeling of students already having diminished student life resources on campus. Just as the dispute ended in the students’ favor, beloved Psychology Department Chair Dr. Charles Waddell resigned when his complaints about a lack of research resources fell on deaf ears. For the already discontented students, the loss of Waddell marked the tipping point of a university facing declining infrastructure and scant resources.

Recent success against the theater catapulted Psychology Club President Charlene Hardnett into action. She organized more than forty campus organizations into a 1972 meeting that adopted a list of campus grievances and conceived Students United. It was an informal association of all university students who were either supporters, sympathizers, or directly involved with the effort. The students did not want a leader or a hierarchical order. They were simply “students” who were “united.”

In an early 1970’s publication of the People’s College Press, Students United declared education was of no value if it did not “speak to the conditions of the oppressed” and did not “ensure . . . the upkeep of the nation.” According to the group, Southern was molding “minds that would submit to the tyranny that exploits and dehumanizes the people of the world” and preparing “a reservoir of lackeys to exploit Black and poor people worldwide.” It wanted to transform Southern so that the university would “aid in the building of a more humane society.”

Beyond this goal, the students complained of inept administrators, a gross disparity in the way Southern and other public institutions were funded, the absence of a legitimate grievance process, dilapidated buildings, rodent problems, poor healthcare provisions, substandard food, the need for department councils, a lack of curriculum content that was relevant to Black social consciousness, a disparity in the treatment of qualified instructors of color and white professors who were either inappropriate with students or ineffective, and a lack of attention to the needs of the neighboring Scotlandville community. Students United called for the formation of a board of representatives that included faculty and students who could review and address student concerns about student life, policy, hiring, retention, and curricula, and vote on important matters.

Mobilization and Fatal Incident with Law Enforcement

Though an HBCU, Southern was operated by an all-white board of trustees, and then-President George Leon Netterville was answerable to them. Students United presented their grievances to Netterville. When ignored, Students United penned numerous statements and letters and relentlessly attempted meetings and negotiations. Avoidance and inaction gave way to weeks of boycotts, demonstrations, and protests and then a demand for a change in leadership. Students United escalated their concerns to the now-defunct State Board of Education and even Gov. Edwin Edwards. Demonstrations, boycotts, and daily meetings continued on campus and even at the State Capitol.

Student participation was often in the ninetieth percentile. Officials responded with arrests. On November 9, 1972, Students United members Ricky Hill and Nathaniel Howard were arrested and charged with “obstruction or interference of educational processes and facilities.” Organizing continued, and more arrests followed. On November 16, 1972, Students United members Charlene “Sukari” Hardnett, Paul Shrivers, Fred Prejean, and Louis Anthony were arrested. Prejean was charged with criminal trespass, while the others were booked on obstruction or interference with an educational institution. These arrests prompted some students to visit Netterville’s office on November 16, 1972, to plea for his assistance in securing the release of those in custody. After the meeting he exited the building under the guise of assisting. Shortly thereafter a call from Southern was placed to law enforcement, falsely reporting that Netterville was being held hostage. Law enforcement officials descended upon the campus with weapons, artillery, and a massive show of force.

Within moments two unarmed Southern students—Denver Smith and Leonard Brown—were dead at the hands of law enforcement. Students Leonard Jackson and James E. Jackson were also wounded. While no university, state, or law enforcement official has ever been held accountable in civil or criminal court, the FBI and several local commissions and bodies issued findings in the aftermath.

Aftermath and Investigation

As the campus community mourned, some members of Students United were in court fighting civil injunctions jointly initiated by Southern and the State Board of Education. Dubbed ringleaders by state and university officials, the following Students United members were “restrained, enjoined and prohibited from entering on the campus”: Charlene Hardnett, Ricky Hill, Nathaniel Howard, Herget Harris, Paul Shivers, Louis J. Anthony, Donald Mills, Willie T. Henderson, and Fred Prejean. Because of these civil and/or criminal cases, most of them had to abandon their studies or pursue their education elsewhere.

Following its investigation, a State Attorney General’s Committee of Inquiry found that Southern “had not developed a well-prepared plan to ensure that students could provide responsible contributions to the conduct of university life.” It also found that “no university personnel were held hostage or forcibly detained,” and it determined that the report of a hostage situation caused the nonviolent students to be met with inhumane force by law enforcement officers. The investigation also found that the “number and variety of weapons brought on campus by law enforcement . . . were far more than necessary to deal with an unarmed group of students.” However, the investigation did not completely exonerate the students. It concluded that Students United exceeded the “bounds of constitutionally guaranteed protest and created disorder on the campus.” A separate inquest by the Black People’s Committee of Inquiry, led by Black elected officials and leaders, felt otherwise. It determined that the students acted in good faith and that Southern officials acted in bad faith and “effected a flagrantly political use of the judicial process to suppress legitimate student dissent.”

Legacy

In 2022, on the fiftieth anniversary of the campus tragedy, members of Students United who were directly impacted assembled. They were given long-overdue credit for the role their movement played in implementing an improved grievance process and Southern getting its own Board of Supervisors in 1975, which granted it more self-governance. The students were also credited for the creation of a Faculty Senate that includes a student member and for the implementation of courses that speak directly to the mission of an HBCU. They were hailed as heroes responsible for an improved educational experience for an incalculable number of people and for future Southern students. They were acknowledged for organizing countless meetings and strategy sessions, authoring volumes of communications, and demonstrating a commitment to nonviolence. In addition they were honored for the personal risks they took and for the template of successful grassroots organizing that they created. During the anniversary festivities, Students United received a proclamation from the Office of Baton Rouge Mayor-President Sharon Weston Broome and a commendation from the Louisiana Legislative Black Caucus. Gov. John Bel Edwards issued an Amende honarable, an open and humbling acknowledgment and apology. In it he acknowledged that the harm “was exacerbated by the punishment of those students who endeavored to fight against the unjust treatment of Black citizens.”