Tchefuncte Site

An archaeological site on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain helps researchers understand Tchefuncte culture from 600 to 200 BCE

R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc. and FEMA

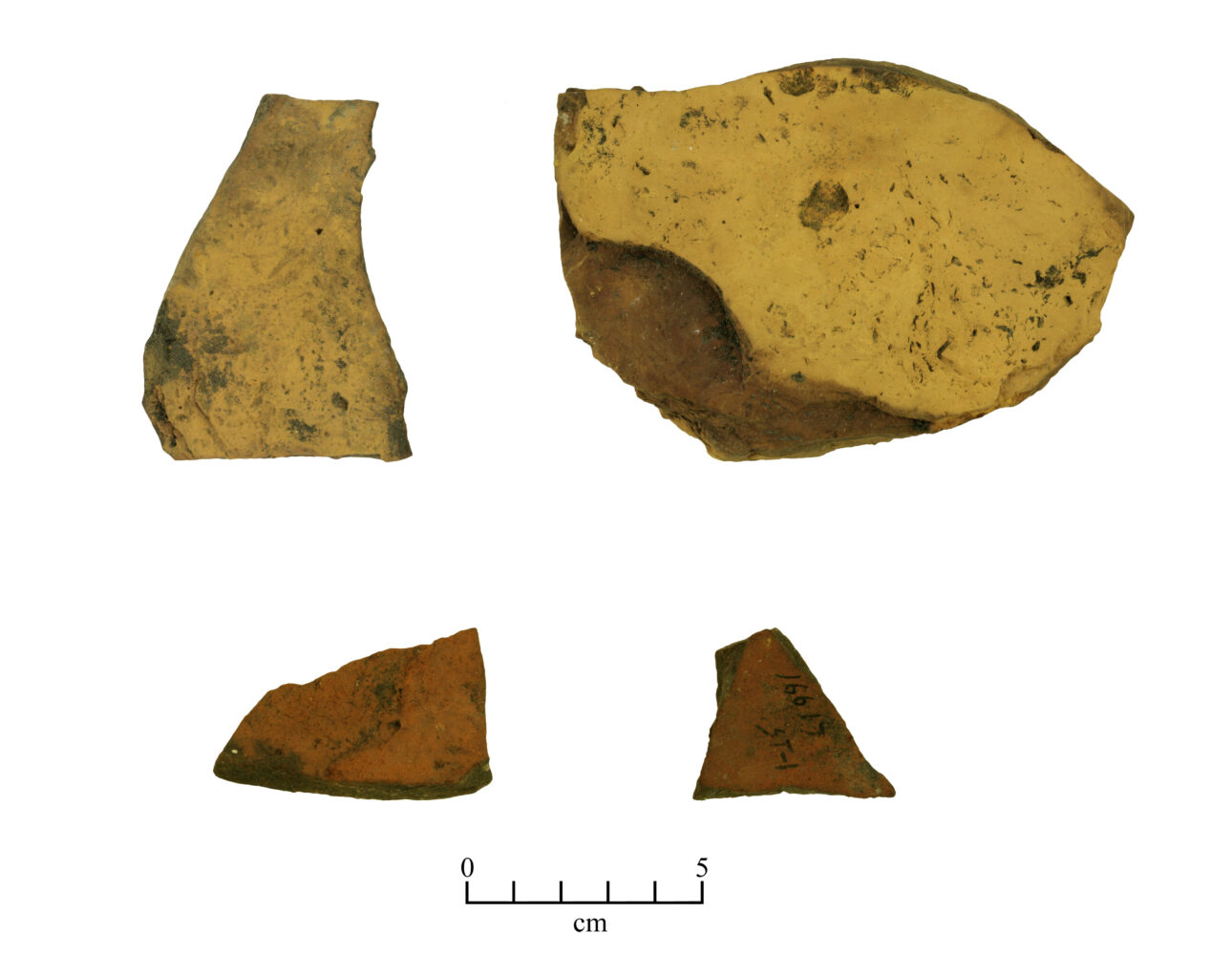

Naturally occurring minerals like limonite (top) and hematite (bottom) could be ground into red, yellow, and orange powder for use as coloring agents to make paints, dyes, and even pigments for tattoos.

The Tchefuncte site is the “type site” for the Tchefuncte culture. This means that information from archaeological excavations at the site in the 1930s and 1940s was used to define and describe Tchefuncte culture for the first time. A summary of the results of those excavations was published in 1945. Recently, the huge artifact and document collection from those excavations were reanalyzed, producing new information gleaned from original field records and from more advanced technologies for analysis (e.g., radiocarbon dating). The nature of the site has been redefined, the occupation of the site has been dated more precisely, and the pottery, bone, and stone tool assemblages have been re-studied using more refined approaches. Although previously archaeologists thought the Tchefuncte peoples were somewhat isolated and less complex than other American Indian groups of the time, the recent studies indicated that the Tchefuncte not only interacted with other groups to procure stone and other items, but also were engaged in activities not seen among contemporaneous cultures, notably pigment production.

The Site

The Tchefuncte site is located in Fontainebleau State Park, near Mandeville, Louisiana. The site consists of two crescent-shaped middens (trash piles), three to four feet high, situated in the freshwater marshes north of Lake Pontchartrain. Midden A was the larger of the two, at 250 x 100 feet. Midden B was smaller, measuring 150 x 100 feet. However, about one-third of the shell from Midden B had already been mined for use in road construction by 1938, when excavations began.

While both middens are generally referred to as shell middens (in which shell is the most visible component of the trash pile), the original field notes indicate that Midden A only had a thin rim of Rangia cuneata (brackish water clam) shell along its southern edge. Midden B, on the other hand, had shell throughout. Before it was mined, it could have contained the shells of hundreds of thousands, perhaps millions, of Rangia eaten over the course of the occupation of the site.

The most extensive excavations at the Tchefuncte site occurred in the early 1940s. Midden B was excavated completely and 632 five-foot squares (the standard square size at the time) were excavated in Midden A. This is an enormous excavation by today’s standards. Each square was dug in six-inch levels, another standard method of the time. Artifacts from each level in each square were placed in separate bags, which now are curated at the Louisiana State University Museum of Natural Science. This use of standard squares and levels allows modern researchers to reexamine the material and see where different kinds of activities occurred at the site, and to see whether there were changes in activities or artifact styles at the site through time.

Tchefuncte Site Artifacts

The most abundant artifacts recovered from the Tchefuncte site were pottery fragments (sherds); over 47,000 pottery sherds were collected from the Tchefuncte site. The abundance of sherds is typical of Tchefuncte culture sites; the quantity of broken pots results from the fact that Tchefuncte potters did not prepare their clay so their pots could withstand the drying and firing process. They did not add temper (an ingredient like sand or crushed pottery) to open up the dense clay for more even firing, and they did not knead the clay to remove air pockets. Without these steps in paste preparation, pots often break during firing or when reheated if used for cooking.

Why Tchefuncte site potters did not prepare their clays as other cultures did is a mystery. They traded with people who did prepare their pastes—potters even borrowed some surface decorations from other cultures in the Southeast. In addition, at the Tchefuncte site, there are small amounts of sand-tempered wares from the Tennessee–Tombigbee Rivers area in northwestern Alabama, so Tchefuncte people had examples of, and presumably used, tempered pottery from elsewhere. It may be that the Tchefuncte regarded pottery not only or even primarily as a cooking tool. The value may have been in the process of producing and possibly displaying the pot. Incidentally, the “exotic” sherds from Alabama indicate a trading network that extended for hundreds of miles, but it is not known if Tchefuncte peoples traveled north to acquire vessels, if Alabama natives came south from time to time, or if vessels were traded many times over short distances, from neighbor to neighbor.

Other pottery artifacts included sixty-seven small tubular pipes, a number that far exceeds the amount of pipes from any other Tchefuncte culture site. Smoking materials may have included a native tobacco leaf and other herbs. Early European accounts of Native American smoking practices suggest that smoking was used in religious rituals, in healing ceremonies, and as a means of establishing friendship and trading relations.

Archaeological sites in south Louisiana often contain very few artifacts made from stone, because there is little stone in the immediate area. However, a little over three hundred lithic (stone) tools were noted in the 1945 Tchefuncte site report. This is a goodly number, considering that the nearest source of stone (Citronelle chert) is fifteen to twenty-five miles north of the site. However, it appears that all of the stone was not included in the report. In the recent reanalysis, researchers identified over 1800 items of stone. These included 350 spear points, knives, scrapers, and choppers made from Citronelle chert. Small amounts of other kinds of stone (quartz, quartzite, novaculite, and non-local cherts) came from as far away as Arkansas and Tennessee.

Sandstone palette fragments and other stones provide evidence for a surprising amount of pigment production at the site. The palettes would have been similar in shape and size to an artist’s paint palette. The Tchefuncte placed minerals on the coarse surface of the sandstone palette and used a harder stone to grind the minerals into a powder. The palette fragments bear the telltale streaks of the pigments, as do some hammer stones, grinding stones, and stone anvils. Limonite, which produces a yellow or (when heated) red powder, was the most popular. Hematite or hematitic sandstone, which yield red or orange powders, were also used. The closest sources for limonite are in north Louisiana or coastal Mississippi, while sandstone could be obtained from central and north Louisiana or the Mississippi coast.

Although a lot of pigment was produced, archaeologists do not know how it was used. Some was used to paint pottery, but the few red-slipped sherds found do not account for the abundance of limonite and hematite. Pigments may have been applied to other things. Both limonite and hematite currently are used for colors in tattooing, and we know that tattooing was very popular in early historic American Indian cultures. Tchefuncte peoples also may have dyed cane for making colorful mats and baskets, and they probably also painted animal skins, dried gourds, wooden objects, and other items that eroded away long ago.

The Tchefuncte site also contained evidence for a healthy bone tool industry—over nine hundred artifacts were bone tools or the waste products of their manufacture. Many tools were made from deer long bones or antler. To produce the tools, the unwanted end (joint) portions of the bone were removed and discarded, leaving only the desirable, straight part of the bone shaft. The most common, recognizable tool was a bone or antler spear point. There were thirty-four of these from the site. Other tools included awls and needles used in sewing and basket making. Only twenty-three shell tools were found; some of these were used as adzes or wedges for woodworking crafts.

The Tchefuncte site produced some unusual artifacts, including pumice. Pumice is volcanic rock that is so light it floats. Archaeologists do not know how pumice arrived at the Tchefuncte site; sometimes pieces can be found along beaches, or it may have been obtained by trade. Today, pumice is used as an abrasive in scouring powders. It is possible the Tchefuncte used pumice to aid in grinding pigments or other materials.

Daily Lives and Deaths

One reason archaeologists dig in squares defined by a grid is to record the location of different activities at a site. At the Tchefuncte site, high frequencies of pottery vessels and stone tools were found in discrete areas on opposite ends of Midden A, suggesting that there were two distinct working or living areas within the site. Clay pipes, however, occurred throughout the midden, suggesting that smoking (or pipe discard) occurred throughout the site. Notably, artifacts associated with making pigments were most abundant in a few squares on the eastern side of Midden A.

Archaeologists reported forty-three burials in Midden A. About half of these individuals were buried soon after death, in shallow pits with their knees drawn to their chests. Others were “secondary burials.” These individuals decomposed elsewhere, perhaps in a special structure. When the time for final burial arrived, the long bones, cranium, and mandible were gathered into a bundle and placed in a pit. No grave goods were found with either type of burial, affirming the general understanding that Tchefuncte peoples were essentially egalitarian, with special status applied only to age group and gender. Burials were found throughout the midden, although more came from the western side. One place burials did not occur was on the eastern side of the site where pigment production took place. Perhaps both pigment production and burial were ritualized activities, but they were activities that needed to be kept separate.

Final Thoughts

One of the striking things about the artifact assemblage from the Tchefuncte site is what is not there. Although there is a lot of evidence that people at the site were making bone tools, there is far more waste material than what would be produced to make the number of finished tools at the site. Where did the finished tools go? Similarly, a lot of stone tools were being made, and pigment production was on a scale higher than seen at any other site in Louisiana. Were the Tchefuncte site people mass producing bone and stone tools and pigments for trade? Whatever the Tchefuncte site people were doing, they were only doing it on this scale at the Tchefuncte site; this was not apparent until the reanalysis was done. The reappraisal of the Tchefuncte site in light of the reanalysis demonstrates the value of preserving archaeological collections for future researchers.