Thomas Sully

Louisiana architect Thomas Sully introduced innovative national architectural trends—aesthetic and structural—to New Orleans.

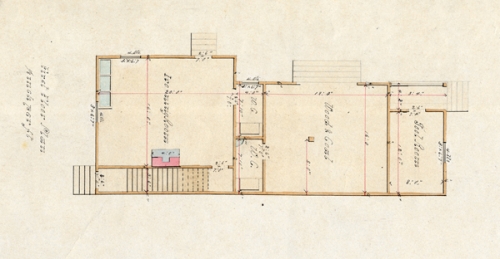

Courtesy of Southeastern Architectural Archive, Special Collections Division, Tulane University Libraries |

Rendering of the Service Building of the Morris Residence, St. Charles Avenue, New Orleans. Sully, Thomas (Architect)

Among the most important Louisiana architects of the late nineteenth century, Thomas Sully introduced innovative national architectural trends—aesthetic and structural—to New Orleans. He also established the state’s first modern architectural office, employing numerous draftsmen and introducing new architectural styles and technology. The designer of institutional, residential, and commercial buildings, Sully proved remarkably versatile as well as inventive in his designs for buildings in Louisiana and Mississippi.

Early Life

He was born on November 24, 1855, in Mississippi City, Mississippi, the child of George Washington Sully and Harriet Jane Green. He was named after his famous great-uncle, the noted Philadelphia portrait painter, Thomas Sully. Though Sully grew up in New Orleans, in 1873 he went to Austin, Texas, to do his architectural apprenticeship with the firm of Larmour and Wheelock. Sully later relocated to New York City to work at the architectural firm of Slade and Marshall, where he was exposed to the latest in architectural styles and technology.

Returning to New Orleans in 1877, he was initially employed as a surveyor, but opened his own architectural practice in 1881. At that time, one of the city’s most prominent architects, Henry Howard, was essentially retired. With few competitors, Sully was able to obtain numerous commissions for both residential and commercial buildings throughout the decade. The Simon Hernsheim house, now known as the Columns Hotel, at 3811 St. Charles Avenue, and his own more modest residence a block away at 4010 St. Charles Avenue are two of his best known early house designs. While the Hernsheim house was in the Italianate style, Sully’s house, built in 1886, was in the then newly fashionable Queen Anne style, and used cypress shingles as an exterior surface treatment.

Career Highlights

From 1889 to 1893, he was senior partner in the firm of Sully and Toledano, working with Albert Toledano. Sully and Toledano were commissioned to build the 1885 New Orleans National Bank at 201 Camp Street, designed in the Renaissance Revival mode and ornamented with red brick and red terra-cotta on its exterior. In 1888, they also designed the Whitney National Bank building at 619 Gravier Street. For this work, Sully used red granite to make the small two-story structure seem grander and more formidable, in keeping with other banks of the era.

Sully often produced more than one design for a single client, the most noteworthy example being John A. Morris, director of the infamous Louisiana Lottery Company. In 1888, Sully designed Morris’s residence at 2525 St. Charles Avenue, which combined the Queen Anne and Colonial Revival styles. That year he also designed the former Morris Building, at the corner of Camp and Canal streets, where he subsequently moved his architectural practice.

During the 1890s, Sully continued to obtain the most prestigious commissions for commercial buildings. Among them is what is thought to be the city’s first steel-framed skyscraper, the Hennen Building, at 201 Carondelet Street, completed in 1895. New Orleans’s soft soil made the construction of tall and heavy buildings like the Hennen a major challenge. Before its construction, Sully traveled to Chicago to see how that city’s architects utilized pilings, sunk below grade, to support tall buildings. In 1922, architect Emile Weil was commissioned to extend the Hennen by two bays along Carondelet Street. He added a floor, thereby eliminating Sully’s roof garden, and also removed some of the ornament on the building’s first two floors.

In 1896, the St. Charles Hotel, the city’s largest nineteenth-century commercial building and the third structure to bear that name, was completed to Sully’s design. (The building was demolished in 1974.) Designed in the Renaissance Revival style, the St. Charles featured a large open piazza overlooking the street through a screen of Palladian arches on the second floor. The terra-cotta for the exterior was provided by the Northwestern Terra Cotta Company of Chicago, a connection likely made during Sully’s earlier visit to that city. Sully’s many designs also included orphanages, a hospital, a theater, a church, and industrial buildings, notably a sugar refinery in Franklin, St. Mary Parish.

In his residential architecture of the 1890s, Sully turned to the popular Colonial Revival style, which had begun to replace the Queen Anne style. Sully’s second personal residence at 1305 South Carrollton Avenue and the John Castles house at 6000 St. Charles Avenue both reflected Colonial Revival style. In the John Castles house, however, Sully, added modern touches such as large windows in the dining and living rooms. Sully also designed a double shotgun house, suggesting that even a modest dwelling was not beneath his attention.

Conclusion

By the turn of the twentieth century, Sully seemed to have deliberately slowed his practice, designing fewer buildings, many of which were for his own use or investment along South Carrollton Avenue. Throughout his career, Sully’s office served as the training ground for New Orleans architects. He worked particularly closely with Sam Stone and Andrew Burton, with whom he formed the firm of Sully, Burton, and Stone, operating from 1897 to 1899. In addition to his architectural practice, Sully was named commodore of the Southern Yacht Club, and dabbled in yacht design, although it is not known if any of his vessel designs were built.

On March 14, 1939, Sully died in the Tudor Revival house he had designed for himself at 7 Richmond Place. His influence lives on in the buildings that continue to stand and the architectural styles he introduced. In addition, Sully set the standard for modern architectural offices, employing numerous draftsmen to produce the detailed drawings needed to construct large commercial buildings. His only child, Jeanne Sully West, preserved most of his architectural drawings and donated them to the Southeastern Architectural Archive at Tulane University, providing invaluable insight into the work of this prominent architect.