Allison “Tootie” Montana

Allison "Tootie" Montana was Big Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas Mardi Gras Indian tribe in New Orleans.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

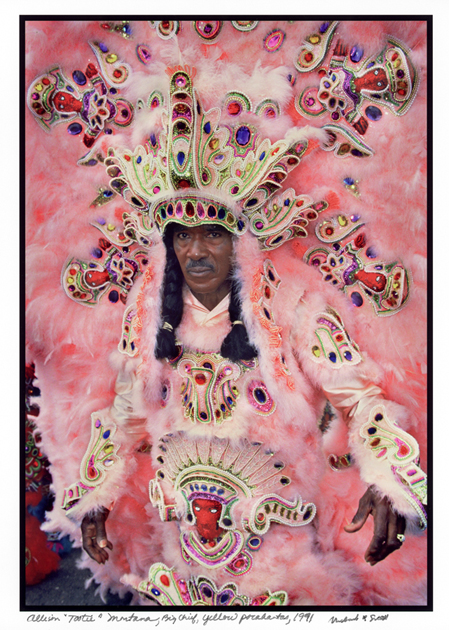

Allison "Tootie" Montana, Big Chief, Yellow Pocahontas, 1991, by New Orleans photographer Michael P. Smith

New Orleans native Allison “Tootie” Montana was among the best-known and most talented of the city’s Mardi Gras Indians. The “Indians,” who are actually African Americans masking as Native Americans, march through the city’s streets on Mardi Gras Day and other recurring dates. Dressing in ornate, hand-sewn costumes or “suits,” groups of Indians sing chants as they travel the city’s streets in search of other tribes. Upon meeting, the chiefs of different tribes compete by insulting each other’s costumes and boasting about the beauty of their own suits. Montana masked for more than fifty years, serving for much of that time as Big Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas tribe. In 1987, the National Endowment for the Arts honored his skill as a folk artist with a National Heritage Fellowship.

Life as a Mardi Gras Indian

Allison Marcel Montana, better known as “Tootie,” was born December 16, 1922, in New Orleans to Alfred Montana, a baker, and his wife. His parents separated when Tootie was young and he grew up in a household of extended relatives. After WWII, Tootie began masking with the Eighth Ward Hunters, and in 1947 he became Big Chief of the Monogram Hunters, a tribe he founded with some friends. In 1956, Montana married Joyce Francis, who never masked herself, but who helped Tootie make his costumes, which might cost several hundred, and even thousands, of dollars to make.

In the late 1950s, Tootie returned to his position as Big Chief of the Yellow Pocahontas, which he held until 1998, when his son, Darryl Montana, replaced him. The next year, Tootie made a new Indian suit and masked as the Executive Counsel of the Yellow Pocahontas. For most of his adult life, Montana worked as a lather, building frames for plaster structures. At first, the frames were made of wood; later, metal was used. In his spare time, he devoted himself to perpetuating the Mardi Gras Indian tradition. His individual artistry was recognized by all; he was a gifted costume designer, a talented dancer and song leader, and an eloquent artistic director of his group.

Montana traces his tradition back to 1880, when his great-uncle, Chief Becate Batiste, founded the Creole Wild West, generally considered the first Mardi Gras Indian tribe; it is believed Becate was part African American and part Native American. The organization of the tribal parade reflects a humorous and fantasy-filled interplay between two cultures, bringing together an African cultural style with Indian motifs. The various chiefs, representing different tribal groups, march in the rear, followed by a large group of supporters who are not in costume and who are referred to as the second line. Ahead of them runs the Spyboy, a costumed scout who moves down the center of the street a block or two ahead and sends back signals to the Flagboy, a bearer of the tribal banner, who in turn relays signals announcing “trouble” or “all clear” to the chiefs.

Cultural Context

In earlier times, the tribes were often known as gangs, and there used to be physical trouble—even bloodshed—when two tribes met. In recent years, Montana said, “they try to outdress one another.” Costumes, songs, and dancing are planned, prepared, and practiced for months before Mardi Gras Day, and thus the black neighborhoods of New Orleans gather in collective Sunday rehearsals, held after church obligations have been met, for three or four hours of intensive dance and musical practice. On Mardi Gras Day, numerous Black Indian tribes debut their new costumes. Hundreds of people parade through the streets accompanied by tambourines and drums, singing in call-and-response style, following groups of black men who are fantastically arrayed in costumes of thousands of hand-sewn beads, plumes, feathers, and rhinestones.

The ancestors of today’s Black Indians were Native Americans of the southeastern United States and African slaves who met in places like the New Orleans French Market. These groups interacted while buying and selling spices, foods, and other goods, and over time developed social networks. The Mardi Gras Indian tribes of New Orleans embody a melding of Native American, Afro-Caribbean, and Afro-American culture. They have retained distinct cultural identities amid the urban environment of New Orleans.

In addition to traditional dress, dance, and music, performance is an integral part of their cultural expression. Contemporary costumes represent African and Native American influences, as well as elements of American popular culture. The Black Indians appear in their elaborate costumes traditionally only twice a year: on Mardi Gras Day and on the Feast of St. Joseph, three weeks later. In recent years, however, many tribes have also appeared at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival in April and on a special parade day, called Super Sunday, in May.

Tootie Montana died on June 27, 2005, while addressing the New Orleans City Council on the city’s treatment of Mardi Gras Indians. He was 82 years old.

Adapted from a biography provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. http://www.nea.gov/honors/heritage/fellows/fellow.php?id=1987_10&type=bio