Troyville Culture

Dating to the Late Woodland Period, from 400 to 700 CE, the Troyville Culture is named for an archaeological site in Catahoula Parish.

Herb Roe

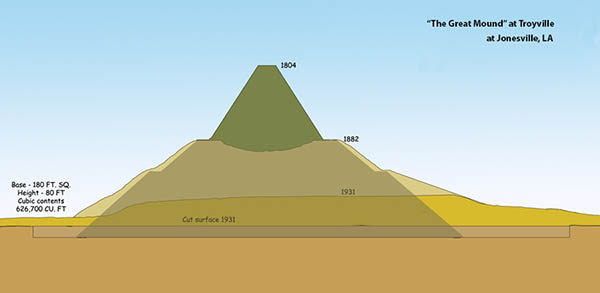

The Great Mound, Troyville Earthworks

The Troyville culture existed in the Late Woodland Period (400 to 700 CE) and was focused on the Lower Mississippi River floodplain. It also extended west up the Red River Valley and east to incorporate the Yazoo and other river valleys in Mississippi. In addition, delta development in south Louisiana provided new habitats for people to settle. While there are a few earlier sites, the Troyville people were the first to really populate the delta.

The Troyville culture is not well understood in Louisiana, in part because it is difficult to distinguish early Troyville pottery from late Marksville culture styles. In addition, many Troyville sites are buried under subsequent Coles Creek culture occupations, so their archaeological visibility is low. Still, there are many more sites bearing Troyville culture artifacts than sites with the earlier Marksville culture artifacts, indicating that population increased substantially between 400 and 700 CE. There were significant changes in artifacts as well. Although the atlatl and spear were still used, the bow and arrow came into use by 500 CE. Projectile points were adapted to this new technology and became smaller and more lightweight. Pottery styles also changed, and reflected considerable communication with cultures in the Florida panhandle to the east. By the end of Troyville times, all of the cultural pieces that define late prehistoric American Indian lifeways were in place.

Troyville Culture: Definition and Important Sites

The Troyville culture was named after the Troyville site, which is in the town of Jonesville in Catahoula Parish. (Troy was the name of a local plantation, and Troyville was an early name for the town.) The culture was once simply summed up as a nondescript, transitional culture existing between the elaborate burial mounds of the Marksville culture and the prominent mound-and-plaza centers of the Coles Creek culture. However, while it is clear that Troyville culture people retained remarkable continuity with the basic core of the Marksville culture, they also were involved in significant cultural changes.

One of the departures from the Marksville culture is the Troyville site itself. The site was described by several different observers in the mid-to-late nineteenth century. However, accounts disagree as to the number and the layout of the mounds. There may have been as many as thirteen mounds, but today, only nine can be confirmed. Eight of these occur within a D-shaped enclosure, while the ninth is just outside the southernmost extent of the enclosure, alongside the Black River. One of the mounds inside the enclosure is unique in the Southeast for its size and shape. Mound 5, or “the Great Mound,” was the second tallest mound ever built in the United States before it was mined for road fill in the 1930s. Built in three stages, the first stage was a square platform measuring 180 feet on each side and 30-feet high. A smaller, fifteen-foot-high platform was built on top of the lower platform. Reports from the 1800s say the third and final stage was a thirty-five-foot cone, which brought the height of the mound to around eighty feet. This mound was connected via a causeway to Mound 4, which was built by the previous Marksville culture.

The Troyville site was considered completely demolished until coring and excavation in the 2000s produced welcome evidence that some early stages of mound construction and portions of the enclosure remained in the neatly divided town lots of Jonesville. Those explorations produced essential information for a reinterpretation of the Troyville site and the Troyville culture. In addition, the work inspired the people of Jonesville to construct a half-size replica of the Great Mound in the southwest corner of the Block High School football practice field, where it is visible from US Route 84.

Twelve miles north of the Troyville site, the McGuffee Mounds site is the only other site known that even approaches the distinctive mound architecture found at Troyville. It too has a long earthen embankment; in this case the embankment encloses six or seven mounds. The largest mound, Mound A, rises up out of center of the embankment. The mound is much lower than Troyville Mound 5, just thirteen feet tall, but local lore has it that until the 1950s, there was a central cone on the mound.

Many later Coles Creek culture ceremonial sites had Troyville culture beginnings. The Greenhouse site in Avoyelles Parish provides a good example of this. There is a ring-shaped Troyville culture earth midden (trash deposit) that underlies, but conforms to, the plan of the subsequent Coles Creek mound and plaza site. The relationships are unclear, but there may have been a common cemetery area used by both cultures.

Troyville Culture Artifacts

One conclusion from the recent work at the Troyville site is that the definitions of the pottery types and varieties used to distinguish Marksville culture from Troyville culture artifacts need reworking. New radiocarbon dates on organic material associated with pottery simply did not confirm previous assumptions about which types were produced by which culture. These results do highlight the fact that there is a good deal of continuity in the style of pottery produced at this time.

Still, there are a few innovations that can help distinguish assemblages of pottery, if not individual pottery fragments. Troyville culture potters made vessels with elaborate lip treatments, and, while a few Marksville pots were painted, Troyville peoples used paints more frequently. Red, white, or black slips (thin paints) made from minerals like ochre, hematite, limonite, and glauconite were applied to the interior or exterior of vessels. Potters also adopted distinctive new designs that bear remarkable similarity to designs made by the Weeden Island culture of Florida. Many Troyville culture (and subsequent Coles Creek culture) pottery types have an analog in Florida, indicating considerable communication between these cultures. No one knows whether the new styles emerged first in Louisiana or in Florida, or whether there was a community of potters across the northern Gulf Coast that developed these designs in tandem.

As noted, the bow and arrow appeared in Louisiana between 500 and 600 CE. For a time, the bow and the atlatl (spear thrower) were both used; spear points were adapted for use with the arrow simply by making them smaller. Ultimately, the relatively heavy, tree-shaped spear points were replaced with light arrowheads like the Collins point.

Daily Lives and Deaths

Because so few Troyville culture residential sites have been excavated, archaeologists’ understanding of the lifeways of Troyville people is limited. Despite the introduction of the bow and arrow, there is no evidence of change in the types or relative proportions of animals hunted (e.g., deer bone does not become more common on sites) and, although postulated, there does not appear to have been changes in warfare as a result of the increased speed and accuracy of arrows.

Elsewhere in the Southeast, some people were domesticating wild seed and grass plants; in Louisiana, hunting, fishing, and gathering wild plant foods (and along the coast, shellfishing) sustained the Troyville populations.

A different approach to ritual emerged at this time, in conjunction with the first platform mounds. Some archaeologists suggest that platform mounds may have been used as stages for public ceremonies. These performances may have been associated with other communal activities such as feasting. At many Troyville mound sites, there are special features—referred to as “bathtub-shaped pits” in the archaeological literature—that appear to have been used to cook foods for large feasts. These pits are often near burial mounds, suggesting feasting accompanied mortuary rituals.

The types of burials were extremely varied, but they suggest an essentially egalitarian society. Interments occurred in mound and non-mound contexts. Some individuals were buried immediately, some were cremated, and some were allowed to decompose until some event (perhaps the death of an honored individual or some astronomical alignment) prompted a mass burial. Grave goods were rare, and the few examples of grave goods were almost always interred with communal burials rather than with single individuals.

The Gold Mine site in Richland Parish provides a good example of burial variability and a remarkable instance of communal grave goods. The site contained two mounds. Although only a portion of the low (three-foot tall) Mound A was excavated, over one hundred individuals of all ages were recovered. True to Troyville-culture form, individuals were sometimes buried soon after death in shallow pits. Other interments were made long after death as bundle burials: the body decomposed elsewhere, perhaps in a special structure (charnel house), and the long bones and cranium were gathered up and bundled together into a small packet for interment. Adults typically had a few child or infant bones buried with them, and in some cases, human bone was simply scattered over the mound. These treatments make it difficult to determine how many individuals were buried in a single event.

The aforementioned communal grave goods were two fired clay figurines with details of facial features and clothing rendered in red, black, and white paint. The hollow-bodied figures are just under one foot tall. Exquisitely executed, both technologically and stylistically, they are unique in Louisiana. Only one other example of a stylistically similar, hollow-bodied figurine exists in the southeastern United States. That is the Buck-Long urn (which may have held crematory remains), from the Buck Mound in Fort Walton Beach, Florida. The similarity of style in the three figurines again emphasizes the close ties between the lower Mississippi River valley and the Florida panhandle at this time.

Final Thoughts

The achievements of the Troyville culture are now recognized as extremely important. Mound 5 at the Troyville site may have been the second tallest mound in eastern North America, while a relatively inconspicuous mound like that at Gold Mine held rare effigy vessels that indicate close ties with other cultures to the east. Many Troyville culture accomplishments were not carried over into later cultures. For instance, the complex construction and size of Mound 5 at the Troyville site was never repeated. Yet Troyville sites often underlie Coles Creek sites, and clearly provided the basis for the vigorous cultures that followed.