Up Stairs Lounge Fire

The act of arson at the Up Stairs Lounge, a gay bar in the French Quarter, was the deadliest fire on record in New Orleans history and the largest mass killing of queer citizens in twentieth-century America.

Johnny Townsend

Patrons of the Up Stairs Lounge, ca. 1973.

Editor’s Note: Warning, this entry contains graphic imagery.

The Up Stairs Lounge fire was a criminal arson at a second-story gay bar named the Up Stairs Lounge, in New Orleans’s French Quarter. The conflagration, which began with lighter fluid in a stairwell that served as the bar’s sole entrance and exit, claimed thirty-two lives and injured at least fifteen others on the night of June 24, 1973.

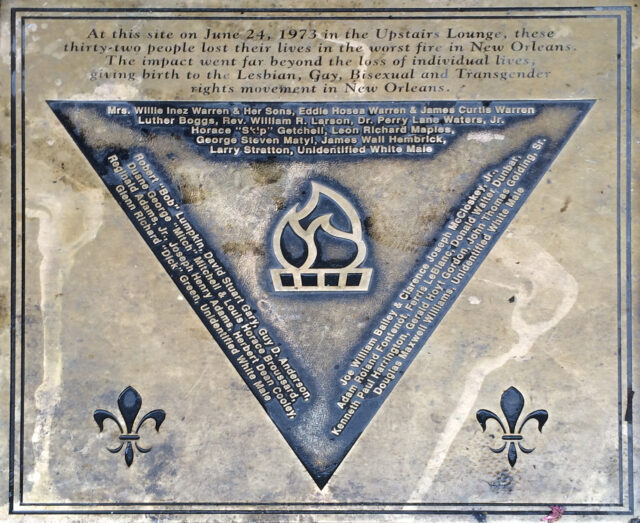

The event was the deadliest fire on record in New Orleans history and the largest mass killing of queer citizens in twentieth-century America. Yet the tragedy received relatively little attention in its day due to anti-gay stigma. Officially an unsolved crime, the fire languished in obscurity for decades but became a topic of historical inquiry in the 1990s. In 2003, on the thirtieth anniversary of the fire, local activists placed a bronze plaque at the historic site as a permanent monument to the victims.

Bar Origins

Bar owner Phil Esteve opened the Up Stairs Lounge at 604 Iberville Street on Halloween night 1970. The bar’s vast interior was concealed from the streets below, and gay groups, dependent on discretion, freely used it for community gatherings. For example, the bar’s rear theater hall served as an amateur playhouse and a worship space for the local Metropolitan Community Church (MCC), a gay-friendly Christian congregation.

Unique for the 1970s the Up Stairs Lounge welcomed gender and racial minorities and encouraged interracial gay courtship. The Up Stairs Lounge anthem, which patrons sang around the bar’s white baby grand piano, was “United We Stand” by Brotherhood of Man. This egalitarian culture, however, was apolitical and working class, and patrons took measures to avoid publicity or arrest for a range of behaviors then categorized as public indecency crimes, such as “dancing with a member of the same sex in an intimate embrace.” The Up Stairs Lounge banned such practices as prostitution and “tearoom sex” (illicit encounters in public places), and police had never raided the establishment.

Lead-Up

June 24, 1973, was a hot summer Sunday. That evening the popular beer-bust drink special drew approximately 110 patrons, who enjoyed bottomless draft beer for the price of one dollar from 5 to 7 p.m. Pianist David Stuart Gary, nicknamed “Piano Dave,” serenaded the crowd, and members of the MCC, which met earlier that day in the Lower Garden District, regathered in numbers at the bar.

Near the end of the beer bust and as the crowd size dropped, a sex worker named Roger Dale Nunez burst through the door and began drunkenly hassling customers. Nunez provoked a fight with a bar regular, who punched him to the floor. As bartender Buddy Rasmussen moved to eject Nunez, Nunez loudly threatened to “burn” the establishment. Minutes later a drunken customer closely matching a description of Nunez purchased a seven-ounce can of Ronsonol lighter fluid at a Walgreens pharmacy down the street.

Incident

Around 7:53 p.m. an unidentified arsonist emptied a seven-ounce can of Ronsonol on the front stairs of the Up Stairs Lounge and produced a spark. Flames rose quickly to the staircase landing, trapping patrons inside. At 7:56 p.m. a downstairs buzzer rang repeatedly within the bar’s main room, and bartender Buddy Rasmussen asked a patron to investigate.

When the staircase door opened, fire met oxygen in the bar, and flames exploded in a backdraft. Carpeting, wallpaper, and ceiling tiles all ignited instantly. Lights shorted out and smoke enveloped the space. Rasmussen, an Air Force veteran, jumped over the bar and began grabbing patrons while repeatedly shouting, “Come with me!” He guided approximately forty patrons through an unmarked rear emergency exit that led them to safety.

Other patrons, trapped in a far corner of the main room, attempted to break through windows. When they shattered the glass, they discovered that iron bars blocked their escape—a safety measure approved by city inspectors. Those who could not shimmy through the fourteen-inch gap between the bars perished in a pile of bodies that Orleans Parish Coroner Carl Rabin would call a “mass of death.” The fire, extinguished by 8:12 p.m., burned for less than twenty minutes. It claimed thirty-two lives and injured at least fifteen others.

The multi-alarm blaze drew thirteen engine companies and attracted hundreds of onlookers. The crowd gawked at macabre sights such as the burned body of MCC’s Reverend Bill Larson, who dangled grotesquely from a windowsill for at least four hours. Members of the news media descended on the scene, and several took pictures of Larson’s corpse. The story, front-page national news on Monday, June 25, receded to interior pages by that Wednesday when the Up Stairs Lounge’s status as a “gay bar” was confirmed.

Crass jokes about “flaming queens” abounded locally, and several fire victims were denied religious funerals or burials, including a local Catholic named Clarence McCloskey. New Orleans Mayor Moon Landrieu, out of the country on a city-funded tour, issued no statements about the fire. After returning to town, Landrieu held a routine press conference on July 11, where a gay reporter directly questioned him about the “homosexual angle” to the tragedy affecting community response. Landrieu responded that he was “not aware of any lack of concern in the community.” New Orleans Archbishop Philip Hannan, silent for weeks, offered brief remarks at the end of a column about human rights in the archdiocesan newspaper The Clarion Herald; these little-seen words of “consolation” appeared without headline or call-out in small print after a jump from the front page. On July 31, three unidentified fire victims and Ferris LeBlanc, a gay World War II veteran whose family couldn’t be located at the time, received burial in a remote potter’s field in New Orleans East.

Investigation

The illegal status of homosexuality hampered the ability of police to trust witnesses and investigate impartially, and the suspect Roger Dale Nunez evaded detectives on several occasions. On August 30, 1973, NOPD closed its investigation without questioning Nunez and declared the fire to be of “undetermined origin.” Nunez’s death by suicide in November 1974 complicated efforts to charge a culprit, even after Nunez’s ex-boyfriend came forward with a claim that Nunez privately confessed to the arson. The Louisiana Office of State Fire Marshal closed a separate investigation without answers in 1980.

Legacy

In the 1990s this historic event received renewed interest. A local writer named Johnny Townsend began to interview fire survivors, and a local MCC pastor named Dexter Brecht began a multiyear campaign to place a permanent memorial at the historic site. Brecht’s efforts succeeded in 2003, when he consecrated a bronze plaque at the location. The Up Stairs Lounge has since become the subject of books, documentaries, musicals, and other works. The political legacy of fire-survivor Stewart Butler, for whom the tragedy inspired an enduring campaign for LGBTQ+ rights in Louisiana, encouraged scholars to examine the fire as a galvanizing event.

New Orleanians held public observances at the Up Stairs Lounge memorial site to honor the fire’s thirtieth, fortieth, and forty-fifth anniversaries. In 2014 the US National Park Service recognized the Up Stairs Lounge as a “place of loss” for LGBTQ+ Americans. In 2019 the New York Times published its first obituary for an Up Stairs Lounge victim, acknowledging the life and death of Reverend Bill Larson.