Westwego Continental Grain Elevator Explosion

The Westwego explosion ranks among the worst industrial disasters in modern Louisiana history and the deadliest disaster to date in the nation’s grain industry.

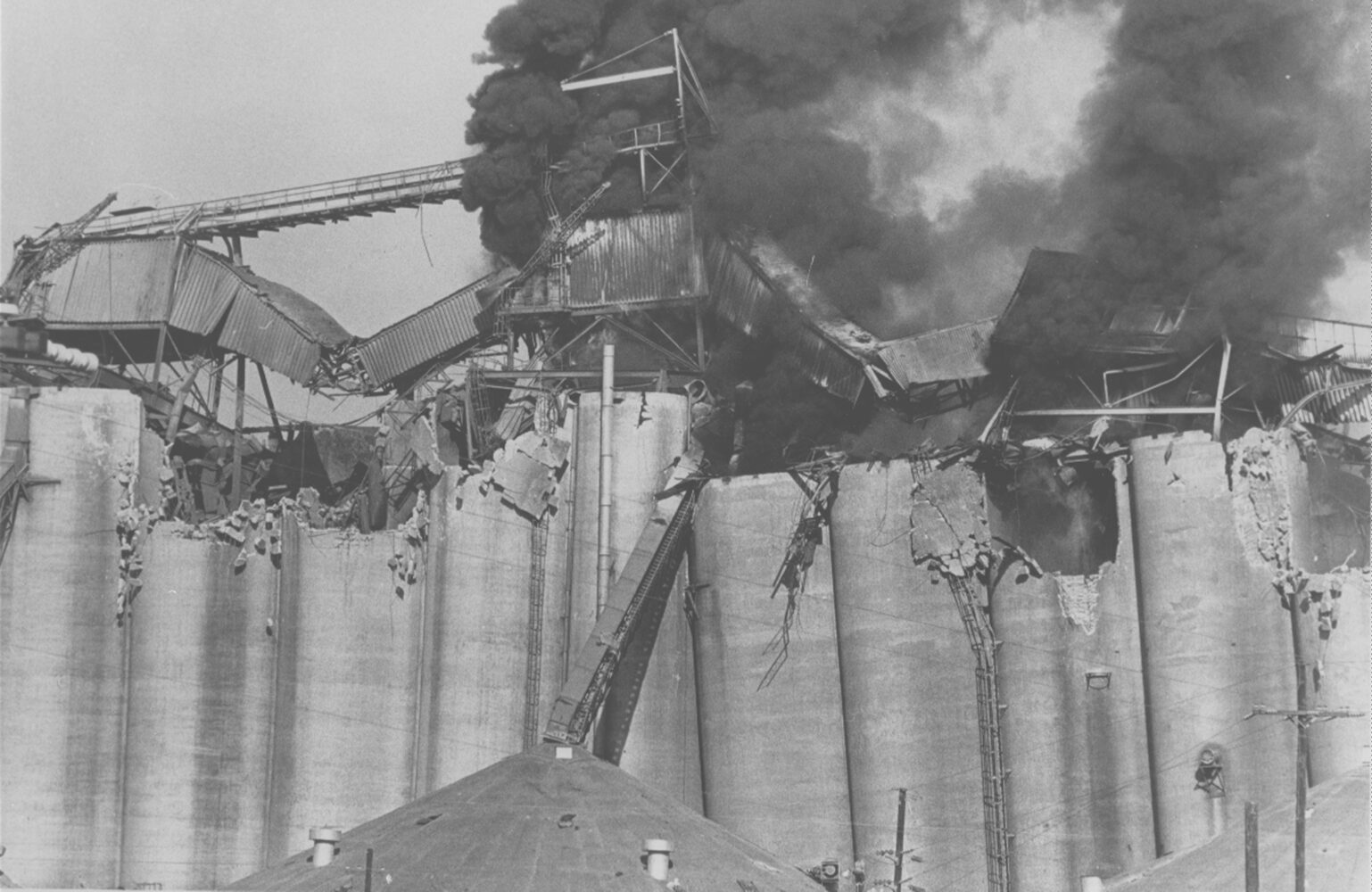

Photo by Bill Haber, AP Photo

The tops of silos at the Continental Grain elevator were blown off during the explosion.

At 9:10 a.m. on Thursday, December 22, 1977, residents of Greater New Orleans heard a thundering blast, and those in west Jefferson Parish and the Uptown neighborhood felt their houses reverberate as debris showered onto roofs and streets. “A tremendous fireball” shot a hundred feet above the Westwego riverfront, followed, as one eyewitness recounted to the Times-Picayune, by a thousand-foot-high “mushroom cloud [of] grain, grain flying through the air, into the river. … You could watch the ducks on the river going for the grain.”

The elevators of the Continental Grain Company had exploded, and it happened at the worst possible time: workers were either clocking in at the facility’s two-story cinderblock office or were stopping by on their day off to collect their company Christmas turkeys. Amid this morning activity, the 250-foot-tall main storage tower collapsed, burying employees beneath a 120-foot-high pile of rubble.

The Continental Grain elevator explosion ranks among the worst industrial disasters in modern Louisiana history and the deadliest disaster to date in the nation’s grain industry. The disaster led to new understandings and safety regulations here and worldwide on containing and controlling combustible grain dust, which is thought to be a contributing factor in the explosion.

Westwego, a municipality of about 12,000 people on the West Bank of Jefferson Parish, had long specialized in industries taking advantage of its deep-draft riverfront and railroad access. Along with lumber, aluminum, oil refining, seafood processing, electric power generation, and transshipment at the Texas & Pacific Rail Yards, Westwego specialized in the business of storage. Companies stored everything from oil, alcohol, and molasses to corn, wheat, soybeans, and oats, allowing producers to wait out world markets until the price was right to ship to supply chains.

Grain elevators found a particularly ideal home in Westwego, as its riverfront was relatively uncluttered and its land-use zoning compatible with their hulking profiles and intricate mechanical equipment required at the Port of New Orleans, one of the busiest grain ports in the world. Continental Grain was one of nine elevators between Baton Rouge and New Orleans and among the largest in the lower South. The $100-million complex’s seventy-three siloes, lined up like a battery of gigantic, concrete tennis-ball containers extending perpendicularly from River Road, could store six million bushels of soybeans, oats, and wheat, brought to and fro on steel conveyors connecting to barges and cargo ships docked in the Mississippi River.

As the Times-Picayune reports, the scene of the explosion on December 22 “looked like a block of a bombed-out European city at the end of World War II.” In addition to the “the twisting, burning wreckage of the giant elevator,” forty-five siloes had their tops blown off. By noon the confirmed death toll stood at ten. The next day it rose to fifteen, including seven federal inspectors. Then someone remembered a group of construction workers who had entered the elevator early that fateful morning, and when their remains were found, the death toll soared to twenty-five. The Times-Picayune’s Christmas Day headline read “Elevator’s Ruins Yield 33rd Body,” as firemen spent the holiday dynamiting their way through rubble seeking others. By New Year’s the final death toll was confirmed at thirty-six. In all, eleven survived.

Rumors abounded as to the cause of the blast. Some said a fire; others, sabotage or a bomb. State Agriculture Commissioner Gil Dozier suggested “it may have been caused indirectly by the two-month-old national longshoremen’s strike that delayed tons of grain shipments along the Mississippi and backlogged them in the elevator,” a backlog of combustible material possibly ignited by “mechanical problems with the conveyor belt.”

It had been a freakishly tragic week for the grain industry, as three other elevator blasts had occurred during December 21–27, in Wayne City, Illinois (one fatality), Tupelo, Mississippi (two fatalities), and Galveston, Texas (fourteen fatalities). The frequency and distribution of these and similar explosions suggested a common cause: dust particles suspended in oxygen become highly susceptible to ignition, be it by fire, spark, friction, or static electricity. As a result, a blast can occur that’s so powerful it obliterates all evidence of what went wrong.

Such was the case with the Westwego explosion, the official cause of which remains undetermined to this day. But that’s not to say it’s a mystery. “This was the deadliest grain dust explosion in modern history,” said Royd Anderson, maker of the documentary The Continental Grain Elevator Explosion, on the fortieth anniversary of the disaster. “It occurred in one of the coldest winters in the 20th century. That, combined with the static electricity and grain dust—which is extremely volatile—more than likely caused the explosion.”

The disaster inspired the convening of an international scientific symposium held in Washington, DC, in the summer of 1978. Industry and academic experts concluded it was far more effective to control dust than to eliminate ignition. “The fact is that you can’t always keep all people from smoking or lighting up a match; and you can’t always keep all bearings from drying out and overheating,” said Dr. Robert Shane of the National Academy of Sciences, a co-sponsor of the meeting. “So at the symposium, the consensus was—remove the fuel.”

From the Westwego tragedy came new industry guidelines and national regulations on containing and controlling grain dust at elevators; moving the main tower, or headhouse, away from peopled spaces; and installing heat sensors to warn of malfunctioning equipment or excess friction. While explosions still occasionally occur, the lessons of the Westwego disaster and the symposium it inspired have surely prevented many more accidents and saved many lives.

Rubble from the destroyed Continental Grain elevator and the damaged siloes were bulldozed throughout 1978, and a smaller $200 million complex with a capacity of four million bushels was erected at the same site. Located one-and-a-half miles up the River Road from Sala Avenue in Westwego, the complex is now run by Cargill. Its profile is a familiar sight to users of the Uptown New Orleans riverfront, and a reminder to all New Orleanians of the terrifying tragedy on that cold pre-Christmas morning in 1977.