Will Henry Stevens

Will Henry Stevens was a pioneering advocate of abstract art in the South and a faculty member at Newcomb College in New Orleans for 25 years.

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection

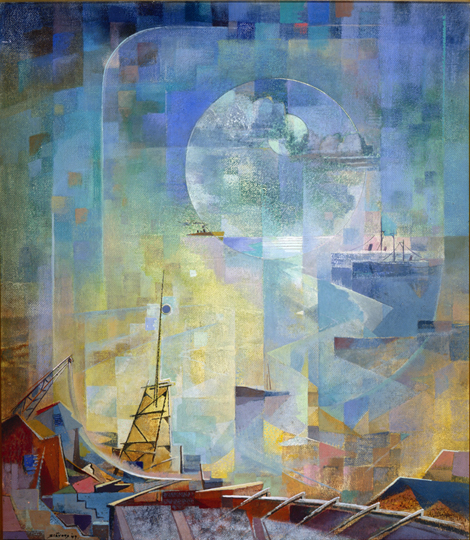

Mississippi River Abstraction. Stevens, Will Henry (Artist)

Over a period of almost three decades, from 1921 to 1948, Will Henry Stevens became an influential teacher at Newcomb College, a significant figure in the art world of New Orleans, a prominent painter who exhibited nationally, and a visionary modernist who is now regarded as a pioneer in the field of Southern art. Inspired by Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, by Sung painters and Chinese philosophers, by Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, and by his spiritual attunement to the world of nature, Stevens pursued an independent path as an artist. He painted what he observed and what he experienced, in pursuit of art that reflected two evolving, and seemingly contradictory, directions in the American art world. Jessie Poesch, a noted scholar on Stevens, wrote, “Stevens was one of the pioneers of modernism in the American South. He was different from most of his contemporaries in that, while he was drawn to experimenting and creating abstract art, he never abandoned working directly from nature.”

Art historian Bruce Chambers has affirmed the unique nature of Stevens’ art. “Stevens worked out an intuitive and highly personal mode of pictorial abstraction that grew directly from regional landscape painting foundations,” he wrote, noting that prior to 1921, Stevens made “annual excursions to sketch around Gatlinburg, Tennessee; Mobile, Alabama; Biloxi, Mississippi; and New Orleans.” Before he moved to New Orleans, Stevens had enjoyed a promising early career. During his years in New Orleans, Stevens remained attuned to the larger trends in the American art scene and shared these with his students and colleagues, while he maintained his annual schedule of trips to New York, summer teaching and painting journeys to Asheville, North Carolina, and other seasonal teaching in Louisiana, Texas, and Virginia.

Stevens was born on November 28, 1881, in Vevay, Indiana, a small town on the Ohio River, located between Cincinnati, Ohio, and Louisville, Kentucky. His father, Edward Montgomery Stevens, was a pharmacist. Young Stevens was raised in an environment where chemicals and drugs were mixed as a matter of business, establishing a model for his later experiments in mixing pastel chalks and colors for his art. Showing an early talent in art, he took lessons with a local artist, Miss Ward, around 1891, attended high school in Vevay, and then studied one year at Wabash College preparatory school in Crawfordsville, Indiana. In 1901, he enrolled in art classes at the Cincinnati Art Academy, studying with Frank Duvenek, Henry Meakin, and Vincent Nowottny.

In 1904, he ended his Art Academy studies and accepted a position at Rookwood Pottery, a leading national art pottery located in Cincinnati. Rookwood sent him to New York City in 1906 to supervise the installation of its tiles at the Fulton Street and Wall Street subway stations. He remained in New York and studied at the Art Students League from around 1907 to 1908, with William Merritt Chase, Jonas Lie, and Van Dearing Perrine. His art was first exhibited in New York at the New Gallery in 1907.

In 1910, Stevens married Grace Hall, an artist who also worked at Rookwood, and in 1912, their only child, Janet, was born. Janet became a jewelry maker and member of the Southern Highlands Craft Guild. During this time he returned to New York and visited Washington, where he discovered Sung dynasty paintings at the Freer Gallery in 1912, a profound and influential event for him, leading to his ongoing interest in Taoist (and related) philosophies. He then taught art in Louisville, Kentucky, from1912 to 1920, and in 1916, initiated trips to western North Carolina, where he painted landscapes of southern Appalachia. Works from this early period include Untitled [Ohio River at Vevay] (c. 1910), Untitled [Indiana Landscape] (1914), and Untitled [Ohio River Valley] (c. 1920-1925).

When Stevens arrived in New Orleans in 1921 to teach at Newcomb College, the city was entering a period of transition, as history and tradition were challenged by modern times, and new buildings and technologies changed the face and the nature of the city. Downtown department stores expanded, and office skyscrapers and hotels were built along Canal Street and in the Central Business District. In response to these changes, William Woodward and others led the preservation movement to save the historic architecture of the French Quarter, inspiring works by Stevens such as Untitled [French Quarter, New Orleans] (c. 1935). Under Huey P. Long’s administration, new public buildings were erected in New Orleans and across the state, while roads, highways, and bridges were constructed, including the Huey P. Long Bridge, the subject of several of Stevens’ paintings, including Huey Long Bridge (1936). Though he was part of this urban environment and spent time with the art and literary circles of the French Quarter, Stevens preferred the world of nature, and often escaped to Westwego, Louisiana, taking an old-fashioned ferry across the Mississippi River to a more remote place, where he found subjects reflecting older times and the natural order he preferred.

Whether in New Orleans or in Asheville, Stevens found his greatest artistic inspirations, and greatest sense of peace, in the natural environment, including the rivers and bayous of Louisiana and the mountains and forests of North Carolina. In New Orleans, he took regular sketching and exploratory trips to the West Bank and the Westwego area, often accompanied by his Newcomb students, where he and they drew cabins, old houses, fishing boats, bayous, and other natural features, as evident in Untitled [Bayou Boats] (c. 1930-1935). In Asheville, where he painted and taught every year, the mountains of western North Carolina provided a primary source of inspiration, as evident in works such as Untitled [Blue Pool] (c. 1925–1930) and Untitled [Mountain Cemetery] (c. 1935). As he explained to his friend, Bernard Lemann, he appreciated how man and nature coexisted in these two locations. “These bayou people have never tried to subdue nature but have harmonized their lives with the natural order. I feel the same way about the mountain people. But on the whole our Western culture has ignored the Oriental point of view. In the West the idea is that man is superior. I think that is a mistake.”

Back in the urban environment of New Orleans, Stevens joined the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans in the French Quarter and came to know the city’s leading artists, writers, and cultural figures, at a time when William Faulkner, Sherwood Anderson, and writers associated with the Double Dealer were active there. One of the South’s oldest art museums, the Delgado Museum of Art (opened in City Park in 1911 and now the New Orleans Museum of Art), strongly influenced by Ellsworth Woodward, gave Stevens an exhibition in 1931. He was also active elsewhere in the state beginning in 1922, when he was appointed the director of the Natchitoches summer art school, where he continued working into the 1930s. In the late 1920s, he also taught in the summers at the Texas Artist’s Camp in San Angelo. Throughout the 1920s and1930s, he exhibited nationally in cities including New York, Cincinnati, Louisville, Kansas City, Houston, Shreveport, Dallas, Indianapolis, and Charlotte. His work also was featured in the New York World’s Fair of 1939. On one of his New York trips during the 1930s, he saw the Guggenheim Collection and was strongly influenced by its abstract and nonobjective works, especially those of Klee and Kandinsky.

Stevens devoted the final decade of his life (1939 to 1949) to exploring an increasingly abstract and nonobjective vision, yet he continued his representational and naturalistic style of painting. In 1941, Stevens had two important exhibitions in New York, one at the Kleeman Gallery, featuring his more naturalistic images, and a later one at the Willard Gallery, featuring his abstract and nonobjective works. He had explained these evolving interests in a letter he wrote to Bernard Lehman. “I do not draw a line between objective and non-objective,” he wrote. “…I am doing both and will continue to, so long as either seems vital to me.” In December 1941, the bombing of Pearl Harbor changed the course of American history as well as the direction of the American art scene. During World War II, galleries and artists entered a difficult and challenging era. Yet Stevens persevered with his vision, his painting, and his teaching. During the summer of 1943, he taught in Lebanon, Virginia. In 1944, he exhibited at Black Mountain College, outside of Asheville, and corresponded with noted artist and Black Mountain College professor, Josef Albers. During the 1940s, he exhibited regularly with the Arts and Crafts Club of New Orleans in the French Quarter. Works from this period include Untitled [Abstraction: Cosmic Landscape] (1939), Passion Flower (1940), Untitled [Abstraction, Red Octopus] (c. 1945), and Untitled [Abstraction: Wooded Hillside] (1947).

In June 1948 Stevens retired from the Newcomb College faculty after twenty-seven years of teaching and painting. An editorial in The Times-Picayune, published on July 7, 1948, suggested how significant his presence in New Orleans had been, noting that “because of his sterling traits and service to art in this community, the impending departure of Will Henry Stevens…causes the most sincere regret.” Continuing, it wrote that as a “landscape painter, and in more recent years as a composer of non-objective paintings into which he put all of the many things he knew concerning color and its harmonies, Mr. Stevens made a mark which, in the opinion of many will grow more distinct, more widely appreciated with the years.” Stevens and his wife returned to live in a restored family home in Vevay, Indiana. He died there, of leukemia, on August 25, 1949. His works are in many museum collections, including the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans (with a dedicated Will Henry Stevens Gallery and the largest public collection of his art); the New Orleans Museum of Art; the Morris Museum of Art in Augusta, Georgia; the Greenville County Museum of Art in Greenville, South Carolina; and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C.