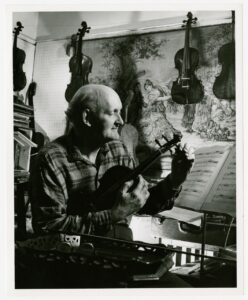

William “Bill” Russell

Bill Russell was one of the most prominent figures in the study and documentation of traditional New Orleans jazz.

The Historic New Orleans Collection

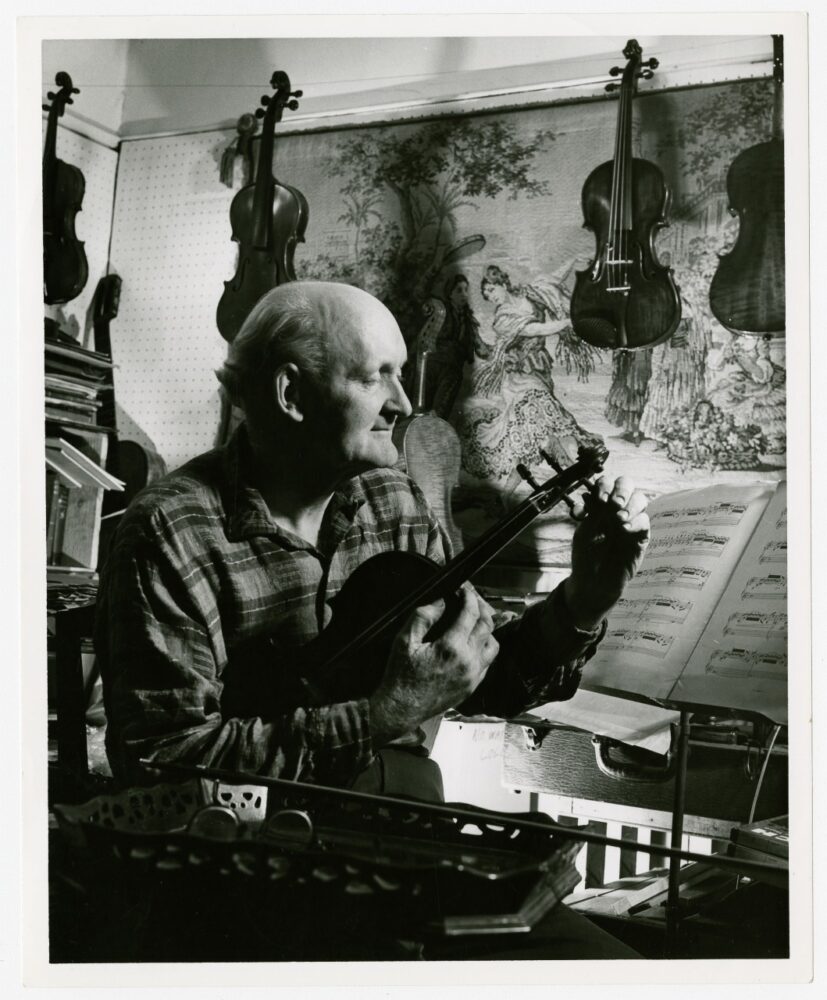

Portrait of William "Bill" Russell tuning a violin, 1958. Joe Budde, photographer.

William “Bill” Russell was one of the most prominent figures in the study and documentation of traditional New Orleans jazz, having devoted his life to recording, chronicling, preserving, archiving, and appreciating the city’s vast musical repertoire. Russell first visited New Orleans on February 26, 1937, where he was quickly captivated by the city’s music scene. He eventually moved there in the early 1940s to hear and record local jazz musicians.

Early Life

Russell was born Russell William Wagner in Canton, Missouri, on February 26, 1905. He changed his name when he became involved in music because of its association with the German composer Richard Wagner and instead adopted his first name as a surname.

Russell played violin from the age of ten, graduated from the Quincy Conservatory in Illinois, and continued to study violin in New York under Max Pilzer in 1927. Russell attended Columbia Teachers College in New York, where he took up composition and taught music in the city during the Great Depression. During this period, he made the acquaintance of experimental composers like Henry Cowell and John Cage and produced his complete oeuvre of eight compositions. From 1934 to 1940, Russell toured with the Red Gate Shadow Players, a group that performed Chinese shadow puppet plays, for which he played Chinese percussion instruments as part of their musical accompaniment. He began collecting early jazz records in the 1930s and resold many through the Hot Record Exchange he founded in 1935 with the artist Steve Smith.

Russell contributed articles to the French magazine Jazz Hot, and in 1939, as a contributor to the pioneering anthology Jazzmen, he began writing about New Orleans music. He played a major role in rediscovering and resurrecting the career of trumpeter Bunk Johnson. In 1944 he founded the American Music record label and personally recorded a historic series of more than sixty jazz recordings, some of which have been re-released on CD. In 1958 Russell became the first curator of the Archive of New Orleans Jazz, now known as the Hogan Archive of New Orleans Music and New Orleans Jazz at Tulane University. In his later years he compiled “Oh, Mister Jelly”: A Jelly Roll Morton Scrapbook (published posthumously), and from 1967 to 1991, he played and recorded extensively with the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra and maintained an almost nightly presence at Preservation Hall.

Composer and Historian

Although not well known, Russell’s modest compositional output remains a pivotal work in the history of the percussion ensemble genre. While Edgard Varèse’s Ionisation was composed in 1931 and is generally considered the first chamber music for percussion alone, few are aware that Russell’s Fugue premiered at the same concert as Ionisation.

Russell’s early works predated and deeply influenced the percussion works of Cage, Cowell, Harrison, and their lesser-known contemporaries. He is the first composer in the Western tradition to integrate African, Caribbean, and Asian instruments with Western instruments and found objects. His experimentation with sticks and mallets, multiple-percussion setups for one player, innovative playing techniques, and the use of the piano as a percussion instrument were present in his work from the beginning—and at a highly innovative yet functional level of sophistication.

The primary characteristic of Russell’s music, the feature that imparts its joy and energy, is that it speaks in a uniquely American style, with influences from popular music and jazz. While Aaron Copland and others gained acclaim by writing in the same vein for European-style orchestras and ensembles, Russell’s choice of the percussion ensemble—which he assembled in a unique collage of Western and non-Western instruments along with found objects—qualifies his work as perhaps the first truly avant-garde, or experimental, American music. His appropriation of classical European forms (such as Prelude and Chorale and Fugue) juxtaposes the inherent dignity of percussion instruments with a delightful, explosive parody of traditional style. Indeed, this aesthetic revolution characterized the percussion movement that Russell helped foster. He died in New Orleans on August 9, 1992. His extensive collection of manuscripts, letters, recordings, and memorabilia is held by The Historic New Orleans Collection.