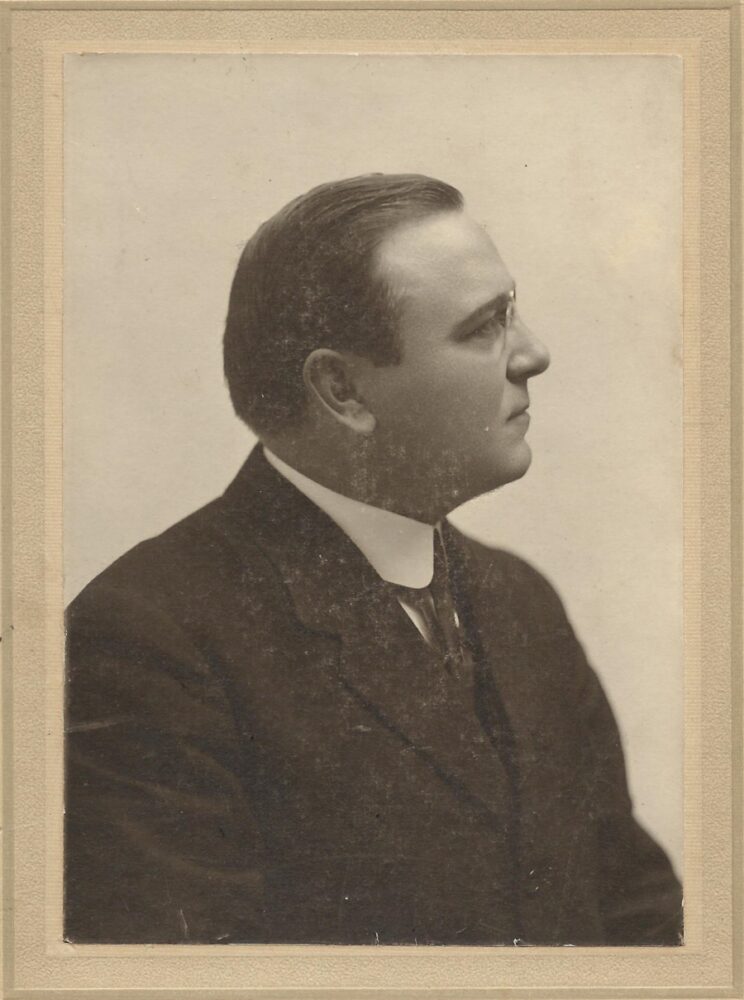

William Christopher “W. C.” O’Hare

Known as the “Father of Ragtime in Shreveport,” William Christopher “W. C.” O’Hare was a white composer, orchestra leader, and music teacher who served as an important link between Black and white musical cultures.

Collection of Sue Attalla

W.C. O'Hare, ca. 1910.

William Christopher “W. C.” O’Hare was a white composer, orchestra leader, and music teacher who became known as the “Father of Ragtime in Shreveport.” He was a contemporary of Scott Joplin, Jelly Roll Morton, and other notable Black musicians from the 1890s through the turn of the century, and as a young composer, he attracted the notice of bandleader John Philip Sousa. O’Hare’s composition “Levee Revels” (1898) was nationally popular and much recorded.

Musical Career

A classically trained musician, who as a young man toured with a minstrel troupe, O’Hare became the first director of Shreveport’s Grand Opera House in 1888 at the age of 21. By the 1890s he was “professor” of music at the Kate P. Nelson Seminary, a prestigious private school for girls in Shreveport, located at the northeast corner of Texas and Grand Avenues. During this time, he and his wife Lottie lived at 134 Grand, very close to Texas Avenue. Much of “The Avenue” was the center of Black social life in Shreveport in those days. The Texas Avenue strip hosted many itinerant Black musicians who would ultimately go on to become major figures in the blues and ragtime genres of American music. Most of these figures also played in the bawdy houses of the nearby red-light district, St. Paul’s Bottoms, as they did in places like New Orleans and Dallas.

Although best remembered for his ragtime tunes, O’Hare mostly produced other types of music. Among his works are an arrangement of Confederate tunes called the “The C. S. A. Grand Medley” and a “mystery dance” called Heliobas. His rendition of “Te Deum” was first performed in St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in Shreveport, and his “We Bend” premiered next door at the B’nai Zion Temple. “We Bend” was a popular piece for Jewish High Holy Days services at the turn of the century, and other sacred music by O’Hare was performed in the Reform synagogue and area churches.

Shreveport’s Grand Opera House saw the first performances of several of O’Hare’s major secular works, many of which went on to success in New York City, though these successes were often short-lived. In September 1898, Sousa introduced O’Hare’s jazz-inspired “Levee Revels: An Afro-American Cane-Hop” (1898) at the St. Louis Exposition. “Levee Revels” was a cakewalk piece inspired by plantation dances and by melodies that could often be heard on Shreveport’s Texas Avenue and in New Orleans’s famous Storyville district. Another such piece was “Cotton Pickers,” which was a hit in New York at the turn of the century.

By 1898 O’Hare frequently traveled between Shreveport and New York as his musical career advanced. Finally, he moved to New York altogether, taking a position with the M. Witmark and Sons Music Company, a major sheet music publisher and, later, a recording company.

As an employee of the Witmark Music Company, O’Hare would arrange music by black composers for band and orchestra, which often involved taking a sung, hummed, or whistled tune and creating a publishable work from it, writing it in formal music notation before arranging it for a band or group of singers. A link between Black and white musical cultures whose career overlapped with a period of enormous creativity in American music, O’Hare died in New York in 1946.