William Haney and Haney’s Big House

William Haney operated Haney’s Big House, a café, bar, and nightclub that showcased Black artists from across the South.

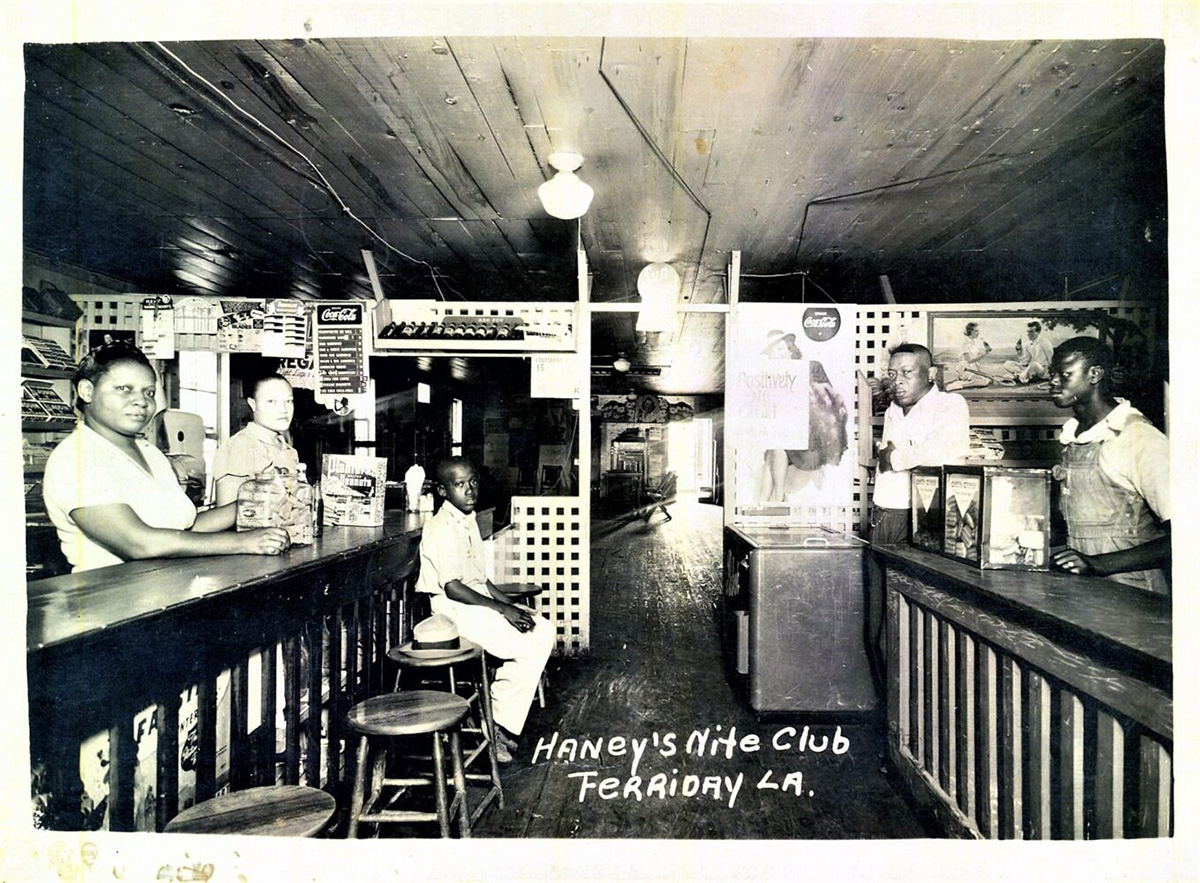

Concordia Sentinel/Gerald Williams

Interior of Haney's Big House, undated.

William Haney was a twentieth-century African American businessman in Ferriday, who operated Haney’s Big House, a café, bar, and nightclub that showcased Black artists from across the South, including performers like Ray Charles, Redd Foxx, and B. B. King.

Early Life

Born on July 2, 1895, in nearby Vidalia to Jim and Emmaline Haney, Haney worked as a truck driver before entering the Army when he was twenty-one years old. He rose to the rank of First Sergeant and was part of Company E in the 805th Pioneer Infantry. He served in France during World War I and returned to the United States in 1919 on the transport vessel the USS Zeppelin.

After the war Haney and his wife Lillie had one daughter. They settled in Ferriday, where he sold life and accident insurance for People’s Life of New Orleans. His Black customer base was so large that he dealt exclusively with the company’s top officials. During periods of flooding in the 1930s and 1940s, many of Haney’s policyholders were unable to work and could not pay their premiums. Haney traveled to New Orleans and demanded that company officials keep the policies in force until his customers regained their financial footing. The company obliged.

Haney’s Big House

Haney also owned rental property and town lots, operated a laundromat, and, in the 1930s, opened a popular barbecue joint in Ferriday along Highway 84, the main thoroughfare through town. The business was housed in a simple structure with a dirt floor. Later, with the construction of a wood floor, barroom, and a nightclub with a dance floor, his operation became known as “Haney’s Big House.” Haney’s also became a popular gambling place with slot machines and high-stakes poker games. Players from as far away as Texas and West Memphis bet thousands of dollars at the poker tables at Haney’s. Sometimes he joined the games.

Haney hired bouncers at times but was able to handle any trouble himself. At five foot eleven, he was not an imposing figure, but he commanded respect and was almost always in a serious frame of mind.

During the early years of operation, Haney’s Big House became part of the so-called “Chitlin’ Circuit,” which provided touring Black artists with venues in which to perform. However, this presented a problem unique to Black performers in the segregated South. Because white motel owners would not house Black people, Haney built his own motel behind his venue in the 1940s.

Over the years performers like Little Milton, Solomon Burke, Roy Brown, Big Joe Turner, Irma Thomas, and Johnnie Taylor performed in Ferriday. Their live boogie, blues, and R&B performances drew so many fans that they spilled out onto the street. Some patrons rode a bus to Haney’s, which also housed its own bus station, with a ticket counter just inside the front door.

Ferriday rock-and-roll legend Jerry Lee Lewis kept up with the artists playing at Haney’s in the “Among the Colored” column in the Ferriday newspaper, the Concordia Sentinel. Lewis told Billboard magazine in 1958 that as a teen he and his first cousin, future evangelist Jimmy Swaggart, would stand on the sidewalk outside Haney’s listening to the performers before returning home to recreate the music on the piano.

Arson and Death

From the 1940s to the 1960s, Haney and Frank Morris were the two most successful Black businessmen in Ferriday. Morris’s shoe shop was a block and a half from Haney’s Big House. Both men placed advertisements in the Sentinel for two decades, with Haney promoting his barbecue business and Morris his shoe repair and other services.

In 1964 Ku Klux Klan arsonists torched the shoe shop. Morris, who was inside the building at the time of the arson, died four days later. No one was ever arrested in the case.

Two years later Haney’s Big House was destroyed by fire, an incident firemen attributed to a faulty ice machine. But the Black community in Ferriday felt Haney was targeted by Klansmen who believed Haney was housing civil rights workers in his motel. Haney chose not to rebuild.

Haney is memorialized with an interpretative marker in Ferriday that reads “Blues Trail: Mississippi to Louisiana” and describes his contribution to the blues.

Haney died in 1972 and is buried in Natchez National Cemetery in Mississippi.