Yellow Fever in Louisiana

The last known epidemic of yellow fever in the United States occurred in Louisiana in 1905. Due to the intensity and frequency of these epidemics, it was often referred to as the "saffron scourge."

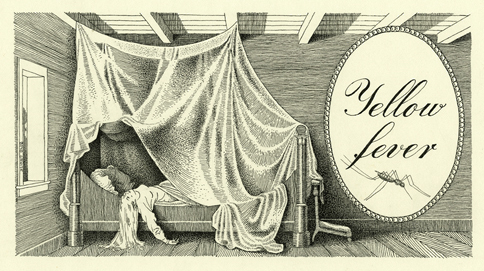

Courtesy of The Historic New Orleans Collection.

Reproduction of a printing plate showing a woman dead from yellow fever. She is lying half in, and half out of her death bed. The plate is from the series "Louisiana Alphabet".

The last known epidemic of yellow fever in the United States occurred in Louisiana in 1905. Due to the intensity and frequency of these epidemics, it was often referred to as the “saffron scourge.” The first case of yellow fever to strike Louisiana occurred in 1769, but the first epidemic transpired in 1796 when 638 people (out of a population of 8,756) died from the disease, translating into a mortality rate of 72.86 per thousand. In the 100-year period between 1800 and 1900, yellow fever assaulted New Orleans for sixty-seven summers. Its main victims were immigrants and newcomers to the city, and for this reason it was also referred to as the “stranger’s disease.” The worst epidemic years coincided with some of the highest levels of Irish and German immigration into the city: 1847, 1853, 1854, 1855, and 1858.

The Disease

Yellow fever is a viral infection transmitted by the common mosquito, Aedes aegypti. It is spread when a mosquito bites a person infected with the virus and then transmits the disease by biting a new person. Its name comes from the fact that a patient’s skin often, but not always, turns jaundiced. This symptom results when the virus attacks the liver. Yellow fever still occurs in South America and Sub-Saharan Africa. There is no known cure for the disease.

Yellow fever occurs in three stages. In the first stage, headaches, muscle soreness, fever, loss of appetite, vomiting, dizziness, and jaundice are common symptoms. Sometimes a brief period of remission occurs, during which many patients recover from the infection. However, the disease sometimes returns, and when it does, it is often fatal. During this last stage, symptoms include multiorgan failure (liver and kidneys), internal hemorrhaging, delirium, and seizures, followed by death. Victims may die as soon as four to eight days after being infected. Patients who recover from the disease are immune for life and cannot transfer the virus to mosquitoes. Consequently, a large population of nonimmunized persons is a condition for an epidemic.Yellow fever was also called the “black vomit” because one of the common symptoms is hemorrhagic bleeding in the stomach. Patients vomit this blood, which has the consistency and color of coffee grounds. It was also called “yellow jack” since areas under quarantine traditionally displayed a yellow flag. “Jack” was sailors’ slang term for “flag.”

Yellow Fever in Louisiana

Yellow fever outbreaks in Louisiana occurred sporadically in the decade following the first epidemic in 1796. Territorial Governor William C.C. Claiborne contracted the disease in 1804, as did his wife and daughter, both of whom died from it. Five years later, Claiborne lost his second wife to the disease. While small numbers of residents continued to suffer from yellow fever every year, the next major epidemics did not occur until 1811 and again in 1817. The latter epidemic spread from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, Saint Francisville, and then to Natchez.

In the summer of 1853, generally considered the worst year of the epidemic, 29,120 people contracted the disease and 8,647 died from it. On a single day in August, 230 deaths were reported. Newspapers and citizens referred to it as the “Black Day.” In August of that year, an average of 1,300 people died each week. By the end of the epidemic, approximately one out of every twelve people had died from yellow fever in New Orleans alone. This figure was much higher among Irish immigrants: one out of every five died from the disease that summer.

It was not until 1900 that researchers discovered the cause of yellow fever. Before this discovery, many different “cures” were tried. Physicians most often relied upon bloodletting, blistering, purging, leeching, vomiting, and mercury. Mercury was especially popular among some physicians, and one doctor, complaining about his colleagues’ overuse of the substance, described a harrowing situation in 1812 New Orleans. Most of the soldiers in three military units stationed in the city had contracted yellow fever. The attending physicians gave each soldier a cup full of mercury with the order to “eat it by the spoonful.” The soldiers died, most likely from a combination of mercury poisoning and yellow fever. It was also common in the antebellum era to shoot cannons and burn barrels of tar during epidemics in the hope of disrupting the dangerous “miasma” in the air, which was believed to be a source of or contributor to the disease.

Yellow fever attacks in Louisiana occurred with less frequency after the Civil War. The populace suffered only three major epidemics in 1867, 1870, and 1878 before the final one in 1905. During the Spanish American War, the US military sent Dr. Walter Reed and his associates to Cuba to study the cause and effects of yellow fever on American troops. At this time physicians believed that the disease was bacterial and transmitted through contact with human waste, similar to the spread of cholera. However, in 1900 the Walter Reed Commission verified that the disease was transmitted by the common mosquito, which bred in any open water container. A Cuban physician, Dr. Charles Finlay, had developed this theory twenty years earlier in 1881, but skeptical colleagues dismissed his published findings.

Once Walter Reed tested and proved this theory, port cities in America, including New Orleans, finally had the knowledge to combat yellow fever. However, many New Orleans residents dismissed the threat posed by mosquitoes. Open wooden cisterns were the norm for collecting drinking water and, unfortunately, perfect breeding grounds for mosquitoes. In 1905, Italian immigrants unloading a cargo ship of bananas in New Orleans contracted yellow fever. Soon the fever spread, and the city asked the federal government for assistance. Orders were issued to fumigate New Orleans as well as to close all open sources of water and screen in cisterns. Residents were fined if they failed to comply. This dictate even included the holy water receptacles located at the entrances of Catholic churches after Archbishop Placide Louis Chapelle died from yellow fever. This final yellow fever epidemic in the United States ended in New Orleans in October 1905 with a total of 452 deaths.