“Equal Rights to All Men”

Divergent coverage of Jim Crow– and Civil Rights–era violence in Louisiana

Published: November 30, 2020

Last Updated: February 28, 2021

Illustration by Nik Richard

Officer Oneal Moore.

Young had fled slavery in Kentucky but was later reclaimed by his owner and sold to a Natchez planter who banished him to the cotton fields of Concordia Parish. After the Civil War, Young was elected to several offices and positions, including the school board and the Louisiana legislature, serving in both the House and the Senate. He also became a merchant in Vidalia, the parish seat.

Young’s name appeared in the top left corner of the front page of the Eagle, the official journal of the parish. This distinction meant that public bodies were required by the state legislature to publish their minutes and other business in the Eagle. The designation of “official journal” also provided the publication credibility as well as a modest income in advertising revenue from governmental bodies.

In the pages of the Eagle, Black people received positive newspaper coverage for the first time in the parish. Prior to the Civil War, coverage of African Americans typically included articles defending slavery or advertisements seeking runaway slaves. In the Eagle, in 1875, Young published an article praising the work of W. G. Brown, Louisiana’s first Black Superintendent of Education. Meetings of the school board were held in Young’s home, where applicants for teaching positions were interviewed. Information on the meetings was published primarily in legal notices, but this was significant for members of the Black community because now they were positively portrayed as educators and leaders.

But before the decade of the 1870s ended, Young was no longer publisher of the Eagle, and gains made for Black people were quickly erased when various white supremacy groups took over the political arena. During the 1878 election, armed white men tampered with ballot boxes in Concordia Parish and threatened Black community members to prevent them from voting, resulting in the old regime of white planters, or their handpicked choices, regaining control of local government.

This disenfranchisement of Black voters was revealed in January 1879, when a US Senate committee investigating the election of 1878 held a hearing in New Orleans. The committee found that in Concordia and Tensas Parishes, an orchestrated move by former Confederate officers and Klansmen resulted in a violent purge of Black officeholders and Black voters. The hearings made public that at least twenty-five Black men, maybe as many as hundred, were slaughtered by the Klan in the two parishes.

As the Jim Crow era was born, David Young relocated to New Orleans. Not long afterward, the Eagle folded. The Concordia Sentinel took over the title of official journal. For the next eighty-nine years, until 1965, one white family owned the Sentinel, the parish’s only weekly. The last family publisher, Percy Rountree, grandson of the first owner, died in 2015 at the age of ninety-four.

In the Sentinel, as in most Louisiana weeklies and dailies, news about sports, church, or schools in Black communities was basically nonexistent prior to 1950. If African Americans were mentioned at all, it was usually to report fears of a Black uprising or the murder of a white person allegedly at the hands of a Black man. During the 1950s to the mid-1960s, the Sentinel criticized the Civil Rights Movement and the politicians who supported it, instead promoting continued segregation.

There was periodic coverage of the Black community but always under the headline of “Colored.” These articles in almost every case were submitted by Black citizens. In 1950, an article in the Sentinel headlined “Among the Colored” listed community, school, and church events. In 1963, another story under the headline “Colored School News” discussed the local Black school’s recent programs involving history, social studies, and 4-H. That same year, a Black family thanked the community for support following the loss of a loved one. It was published under the category “Colored Card of Thanks.”

By the mid-1960s, when the Rountree family’s nine decades of ownership of the Sentinel came to an end, the state, like much of the South, was in turmoil. The Ku Klux Klan had become a feared terrorist organization, and in Ferriday, Louisiana, in 1964, the Klan murdered African American Frank Morris, who for three decades had operated a shoe shop with a loyal Black and white clientele.

On December 10, 1964, a front-page headline in the Sentinel announced: “Fire Destroys Frank’s Shoe Shop in Ferriday Thursday.” The article noted, “[O]wner Frank Morris (colored) is reported to be in critical condition from burns. The building was completely demolished.”

There would be no follow-up on the Morris murder case in the Sentinel until 2007.

Four days after the fire, Morris died at the hospital in Ferriday. After his second day as a mortally wounded patient, he had gone into a coma, but not before talking to FBI agents. In a morphine daze, he gave a somewhat confusing physical description of the two Klansmen who torched his shop. That was historic. It was the only time during the era that a victim of Klan violence lived long enough to describe his attackers.

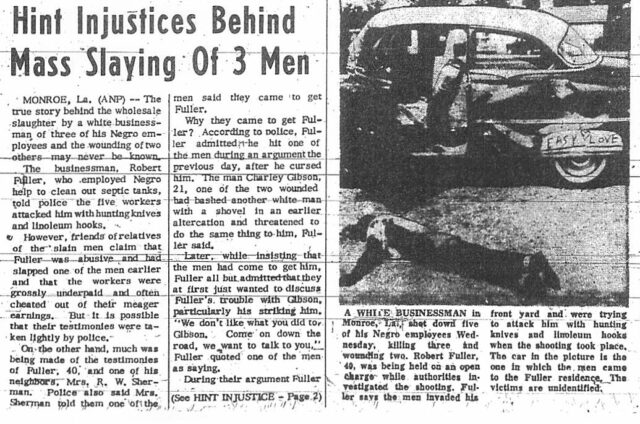

The headline from the July 23, 1960, edition of the Louisiana Weekly stands in contrast to that of the Monroe News Star, which led with “Five Armed Negro Men Shot by Employer.” Louisiana Weekly Archive, Amistad Research Center

Though the Sentinel abandoned this local story, the NAACP publication the Crisis, other Black newspapers and periodicals, and major national newspapers continued to report on the Morris murder. The Crisis found an informant who said “there was a burst of flames, a loud pop and Mr. Morris came running out of the building, his clothes on fire. The flames were beaten out, but he later died at the hospital.” In Memphis, the Black-owned Tri-State Defender picked up some of its coverage from the New York Times but added its own conclusion concerning the probability of resolution: “Frank Morris is dead and there seems every likelihood that his death will come no nearer solution than any of the atrocious racial crimes, which are plaguing the Deep South.”

When another white journalist, Sam Hanna, a longtime political reporter in Louisiana, bought the Sentinel from Percy Rountree in 1965, there had been, inclusive of Morris, at least two Klan murders of Black men in Concordia Parish. The other was Joseph Edwards, whose body has never been found. Since there were no investigations by local law enforcement, the FBI moved in, but agents would not comment on the cases to the press. The Justice Department would not comment either.

Instead, Hanna aimed his press coverage at the sheriff, Noah Cross, and his violence-prone chief deputy, Frank DeLaughter. Both lawmen were Klansmen, the FBI learned through its investigation into the murder; they considered DeLaughter a leading suspect in the murder of Frank Morris. Although Hanna was not privy to that information, he knew that the sheriff and deputy were otherwise involved in criminal activities.

Hanna’s long-term coverage of the corruption in the sheriff’s office helped lead to the federal conviction of the sheriff and the deputy in the early 1970s—the sheriff for racketeering in connection with the operation of a brothel and casino in the parish, and the deputy for police brutality. Both went to federal prison, and perhaps more importantly, they were forced to turn in their badges forever. (In 2007, two of Hanna’s children, now operating three Louisiana weeklies, supported a multi-year investigation by the Sentinel into the Frank Morris murder as well as other murders linked to a Klan cell known as the Silver Dollar Group. The Sentinel published approximately two hundred stories in the series.)

In 1960, four years before the murder of Frank Morris, the horrendous shotgun murder of four Black men (Marshall Alfred Johnson, Ernest McFarland, and brothers Albert Pitts and David Lee Pitts) and the wounding of a fifth made news in Monroe. The men’s employer, Robert Fuller, a future state Klan leader and the owner of a septic tank pumping service, was arrested for the killings, but a grand jury refused to indict him. The case drew both statewide and national coverage, most of it concentrated on Fuller’s claim of self-defense and police accounts of Fuller’s story.

But the African American publication the Louisiana Weekly, based in New Orleans and founded in 1925 by Orlando Capitola Ward Taylor and Constant C. Dejoie Sr., reached out to the Black community and the dead men’s families. The paper’s story on the killings revealed a major contrast in coverage.

The paper reported that the true story of the “wholesale slaughter” by a white businessman “may never be known.” A reporter for the paper talked with friends and relatives of the victims, who were aged nineteen to twenty-four. Those interviews alleged that Fuller was abusive and violent toward his Black employees, who were underpaid and sometimes cheated out of their earnings. When the men attempted to peaceably confront Fuller about their pay and the fact that Fuller had hit another Black employee the day before, Fuller pulled a shotgun from his truck and opened fire. In less than a minute, all five Black men were lying on the ground bleeding, three apparently killed instantly. The murder scene was reported to be horrific.

Fuller was one of only two Klansmen arrested by police for a racial murder in Louisiana in the 1960s. Both men walked free; the grand jury hearing Fuller’s case refused to indict, and in the other case, the grand jury was never asked to indict. The murder in this second case happened six miles north of Bogalusa in 1965. The first two Black deputies in Washington Parish were patrolling in their police car through the village of Varnado when they were shot up by a group of Klan assassins passing by in a pickup. The driver, Oneal Moore, a father of four daughters, died instantly. His partner, Creed Rogers, severely wounded, broadcast news of the attack over the police car radio, providing a detailed description of the pickup. Less than an hour later, Ernest Ray McElveen, a forty-one-year-old Klansman and decorated World War II veteran, was apprehended driving through Tylertown, Mississippi, just north of the Louisiana line, in the pickup Rogers had vividly described.

The white sheriff who hired the Black deputies, Dorman Crowe, traveled to Mississippi and escorted McElveen to Franklinton, the seat of Washington Parish, where he charged him with murder. Without enough evidence to hold him, however, the district attorney released the suspect eleven days after his arrest on $25,000 bond paid primarily by Klansmen. Although a grand jury looked into the matter, no action was taken. After a half century of intensive investigation, the FBI and Justice Department could do no better.

In Bogalusa, which combined with the rest of Washington Parish had the largest Klan membership in the state, the white publisher of the Daily News wrote multiple stories on the murder of Oneal Moore during the 1960s. Critical of the Klan, the publisher, Lou Major, was himself the victim of cross burnings, threats, and harassment. A white television reporter from Baton Rouge, beaten by the Klan in 1964, told FBI agents that Klansmen planned to beat Major as well. The Klan boycotted the Daily News, threatened advertisers who did business with the paper and sometimes followed Major about town.

The Daily News also covered the Civil Rights Movement in Bogalusa—the marches and demonstrations and the federal court cases testing the newly passed civil rights laws. If Major did not write the story himself, he printed articles provided by United Press International.

Overall, Major’s coverage of the murder and the racial turmoil in Bogalusa may have been the most courageous and comprehensive by a white publisher in the state during that era. But, like most white editors in Louisiana and the South, Major occasionally editorialized against civil rights groups, particularly the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE), which assisted in community activism. And even the Bogalusa Daily News, whose coverage was exceptional, failed to reach out to Black residents for comments on the attack on the two Black police officers or gauge their feelings on the progress of civil rights legislation, not to mention their economic and educational needs.

Fourteen decades have passed since David Young was robbed of his vote and his office. But during his time as editor and publisher, the Concordia Eagle reflected the astounding changes and hopes for Black people that came immediately after the Civil War. Although Young was forced to leave the parish during the Klan takeover in the late 1870s, African Americans continued in the following decades to publish newspapers that provided comprehensive coverage of the Black community. Notably, the Louisiana Weekly’s coverage of the Klan murders during the 1960s are relied upon today by journalists who are still working to unravel the many unsolved cases.

Stanley Nelson is editor of the Concordia Sentinel in Ferriday and author of the book Devils Walking: Klan Murders Along the Mississippi in the 1960s (Louisiana State University Press, 2016). A finalist for thethe Pulitzer Prize for Local Reporting in 2011 for his coverage of the Frank Morris and other civil rights–era murders, he is an adjunct professor at the LSU School of Mass Communication. In that role, he is co-leader of a team of students that actively investigate and report on Klan murders and on African American organizations from the civil rights era.

This article is part of Split Press: Democracy, Race, and Media in Black and White, a four-part multimedia series exploring the relationship between the media and African American and Afro-Creole experiences of citizenship and civil rights in Louisiana. Part of the Democracy and the Informed Citizen initiative, Split Press is a project of the Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities made possible by a grant from the Federation of State Humanities Councils with the support of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. For additional Split Press coverage, stay tuned to 89.9 WWNO New Orleans and 89.3 WRKF Baton Rouge.