Magazine

Evangeline Downs

From bush tracks to bright lights in Acadiana

Published: June 1, 2016

Last Updated: May 6, 2019

The idea of a new track began in 1964 with small talk and was sealed with a handshake.

“I was running the stockyard at the time,” former track manager and president of Evangeline Downs Charles Ashy recalls. “On Tuesday afternoons, I’d come to the sale barn when the cattle were coming in. This fellow with the Louisiana Quarter Horse Association says, ‘We need some help with these running quarter horses to get points on ‘em.’”

In the language of horse racing, “getting points” meant accumulating the necessary stats for a horse to earn the credentials needed to qualify for major, high stakes races. A local racetrack would provide a venue for local horse owners, trainers and jockeys to test their mettle outside the region’s storied “bush tracks” and attract competition from around the nation.

Through Ashy’s gift of persuasion, quarter horse enthusiasts and thoroughbred connoisseurs came together with civic leaders and businessmen who recognized the economic opportunity a local racetrack represented. They dreamt of a venue where the centuries-long horseracing traditions of Acadiana would attract thousands of racing fans to Lafayette Parish, just as people flocked to Hialeah Race Track in Florida or Churchill Downs in Louisville, Kentucky. Why not here?

Their dream would not come cheap. With lending banks particularly conservative in the mid-1960s, the organizers turned to the community to raise the $2 million start-up cost. In the time before crowdfunding, ”social media” meant sitting down with your neighbor for a face-to-face discussion of risks and rewards. Little by little, Ashy and the other businessmen sold their vision to those willing to make the gamble. Stakes in the newly formed corporation were limited to $10,000, and the company issued debenture bonds for the balance.

On the best race days, the track at Evangeline Downs was rated “fast,” offering an opportunity for record-setting performances. Courtesy of the Bob Henderson Collection, Dupre Library, University of Louisiana, Lafayette

The Carencro site was selected and construction began on the track and the grandstand soon after. When the stalls were finished and ready to receive horses, Breaux Bridge Crawfish Festival Queen Lydia Gonzales and General Track Manager Richard Thompson marked the occasion by presenting a sack of carrots and a bale of hay to the first horse off the trailer, remembered to this day by many as Rain Flower, the four-year-old colt of trainer Pola Benoit. The track opened April 28, 1966.

“From day one, they couldn’t get all the people in there,” says Ashy.

Weekend parking lot surveys from 1970 indicated that some 60 percent of attendees came from outside Acadiana. “Texas had no tracks,” Ashy explains. “None in Mississippi. None in Alabama.” Chartered busloads arrived from Houston on race days and Greyhound Bus Lines regularly offered weekend service direct from Houston to Evangeline Downs.

Ashy recalls an afternoon when two managers noticed a furniture delivery truck pull up to the gate just before post time for the first race. The managers watched, puzzled, as the driver walked to the back of the truck, rolled open the freight door and installed the ramp. Nobody had ordered any deliveries that day. Instead of furniture, 30 or so racing fans hurried out of the back of the truck.

“They’d been on a chartered bus from Houston that broke down in Beaumont, and if they had waited on a replacement bus to arrive, they would’ve missed several of the races,” Ashy says, laughing. “They somehow convinced this delivery man to take them into Lafayette to arrive in time to bet the Daily Double.”

Visitors soon discovered the appeal of Cajun and Creole hospitality—and cuisine. Evangeline Downs’ public address announcer Gene Griffin kicked off races with “Ils Sont Partis!” (And they’re off!) Though the wait for reservations could stretch to four weeks, the clubhouse kitchen became famous for its Louisiana-French fare, including “thick steaks or delicious seafood specialties such as crawfish etouffee, fried butterfly shrimp, stuffed flounder and gumbo,” as described in Evangeline Downs’ 1979 brochure.

Cuisine and hospitality weren’t the most important factors in the success of Evangeline Downs. Horsemanship was woven through the Cajun and Creole culture of the region, and the track became the nexus for those traditions.

For more than a century, long before the lights blazed above Evangeline Downs, South Louisiana’s landscape was scattered with unsanctioned, rural dirt tracks, often adjacent to a barroom with a dance floor. When young Cajun boys weren’t working their horses on the headlands of sugarcane fields, they were racing them, barefoot and bare-chested, at those bush tracks.

Handling horses had been a part of Cajun life, a skill perfected through the cattle ranching that Acadians practiced in Canada and brought with them when they migrated to Louisiana in 1765. For the Creoles, the business of herding cattle and riding horses on the open prairies dates back even earlier. Cattle could roam the Louisiana grasslands au large, with no fences confining them, necessitating the kind of expert horsemanship that became a way of life for many. The hard work demanded new outlets for play and performance, giving rise to the legendary bush tracks of Acadiana.

“They opened it,” says Ashy, “and from day one, they couldn’t get all the people in there.”

By the mid-1950s, nearly every community—Maurice, Henderson, Coteau Holmes, Abbeville, Churchpoint, Ville Platte, Eunice, Breaux Bridge—had at least one bush track. On weekends, neighbors gathered and horse owners trailered in their stock to compete in regular races, some responding to a specific challenge from another horseman. Although the competition was usually friendly, bush track betting could get a bit raucous.

“After Cajuns have a few beers, their horses are faster and the women are prettier,” says Don Stemmans with a laugh. Stemmans owned and operated a bush track known as Carencro Raceways from 1968-1973.

The bush tracks became the training grounds of a number of notable jockeys hailing from Acadiana.

“The bush tracks—it made me,” says three-time Kentucky Derby winner Calvin Borel from Catahoula, LA. “If you can ride in the bush tracks, you can ride anywhere.”

At bush tracks, Cajun boys as young as five or six mounted horses and rode until they could apprentice at sanctioned tracks like Evangeline Downs, where the opportunity of a professional racing career loomed. For many young bush track jockeys, Evangeline Downs became a rite of passage and provided them a chance through close family and community ties.

“They got experience instantly here at Evangeline Downs because their daddies had 10 horses, their uncles had 10 horses, their cousins had 10 horses, and they put those kids on their horses,” explains Ashy.

Among the world class jockeys to emerge from Evangeline Downs were Eddie Delahoussaye (New Iberia), Kent Desormeaux (Maurice), Randy Romero (Erath), and the Borel brothers.

“Most of the Cajun kids grew up around match races. When Evangeline Downs came around, it gave them a chance to race a big-time track,” says Delahoussaye. “That track helped us to get a foundation and then go on and do a lot of great things.”

Not all the great riders wanted to be career jockeys. Some opted to remain in their hometowns, while others wanted to earn money for college. Dennis Herpin, a jockey from Morse, began riding bush tracks in Carencro at 11, sometimes competing against a horse with nothing in the saddle but a clanging cowbell or a live chicken for a jockey. Herpin holds hundreds of Louisiana track wins, including victories at Evangeline, Delta and Jefferson Downs. Beginning in 1971, during the nine seasons when Herpin was competing at Evangeline Downs, he was also attending the University of Southwestern Louisiana (now University of Louisiana at Lafayette), where he earned multiple degrees that carried him onward to pharmaceutical school. Evangeline Downs made it possible.

Evangeline Downs created economic opportunities for more than just the famous jockeys and the original investors who received 100 percent return on their $10,000 within two years. The track generated income for trainers, veterinarians, farriers, tack suppliers, clubhouse waiters and the managers greeting people at the gate. In 1979, Evangeline Downs’ brochures listed 17 hotels and motels within a few miles of the track. Vacancies were rare.

Evangeline Downs Director of Racing Charles Ashy (2nd from left) and Norman Faulk introduce retired jockey Eddie Acaro, one of the greatest jockeys in the history of American thoroughbred racing. Courtesy of the Collection of Charles Ashy

“The business people in the oil field were there Monday through Friday,” says Ashy. “And when they were walking out of that hotel room, the racing people were coming in.”

Not everyone ate at the clubhouse. Along with hotels, many fine restaurants opened up on the Evangeline Thruway, clustering near the track. Visitors and locals alike came to appreciate that the fine dining in Acadiana could also mean linen tablecloths and nice china at establishments like Angelle’s, Carol’s, Preajean’s and Enola Prudhomme’s Cajun Café.

Texas folk music singer Lyle Lovett remembers the vibrant restaurant scene in the region during the days when, as a kid, he’d come to Evangeline Downs on race nights with his uncle, a horse trainer. “If my uncle’s horse won, we ate at Don’s,” Lovett told audiences during one performance in Lafayette. “If he lost, it was the Pitt Grill.”

The promise of economic benefits had persuaded the Lafayette Police Jury to endorse the track proposal in 1964. “This jury, being for progress,” they declared, “should encourage any legal venture to aid the economic growth, to promote conventions, tourism and opportunity for this parish.”

The founders of Evangeline Downs went further to ensure economic advantages for the community by writing and promoting the passage of new legislation regulating profits. Dated June 6, 1967, LA Act 124 mandated that annual surplus revenues of $360,000 must be directed to the State Board of Education for capital improvements at three universities in the region: $260,000 to the University of Southwestern Louisiana (UL Lafayette), $50,000 to McNeese State University and $50,000 to Nicholls State University. The legislation also directed $200,000 annually toward local government, with two-thirds of that going to the parish and one-third going to the municipality of Carencro.

At the start of its 14th season in April 1979, newspapers reported that the track employed 500 local residents with an annual payroll of more than a million dollars. Four million spectators had attended races and nearly $18 million had been paid out in purses to horse owners and trainers. Since 1967, the University of Southwestern Louisiana had received $3.5 million, with $300,000 distributed to both Nicholls and McNeese. According to findings by LSU’s Department of Agricultural Economics and Agribusiness, Louisiana’s horse racing industry as a whole had a $460 million impact on the state in 1979.

Despite the boom, Evangeline Downs was not immune to the new forms of gambling roiling through the racing industry nationwide. The challenge for any track is to keep purses high enough to attract—and retain—horses, riders and fans. Televised via satellite, Off Track Betting (OTB) allowed each track within a state to offer their races to other tracks in that state. People no longer had to be physically present at the race where they were wagering—attendees at Evangeline Downs could bet on races at the Fairgrounds in New Orleans and monitor the results on clubhouse televisions.

At the request of Fairgrounds owner Louis Roussell, III, Ashy worked successfully to gather industry support for passing OTB legislation in 1988. To dispel skepticism among the operators of other Louisiana tracks, Roussell and Ashy took the plunge. Though the new business model provided the higher purses that attract good races and enable horsemen to continue doing what they love, OTB came with a risk: betting on televised races could diminish the number of customers gathering in the grandstands to watch the races, dining in the clubhouse, lining up for concessions or crossing state lines to spend money in Louisiana. The legalization of Intrastate Racing, whereby tracks could accept bets on races at out of state tracks, and the rise of OTB betting parlors continued to thin out the race day crowds around the country, which included Evangeline Downs’. The changes in the industry disrupted the livelihoods of the people whose lives revolved around horse racing. For Ashy, what mattered most was finding the means to ensure the survival of the horse culture that had created Evangeline Downs. One possibility would play a pivotal role in the fate of the track.

“I was reading an article about a Delaware track that was going broke,” Ashy says. “After trying out the slot machines for 30 days, its purses went from $30,000 a day to $300,000 a day.”

Video poker and slot machines were new strategies for attracting audiences to the track, merging horse racing with casino gambling to create a new breed—the “racino.” Again, Ashy saw a means for survival that would require cooperation and new legislation.

He called together track owners, breeders and industry officials to plead for a consensus.

“I started the meeting, told them what it was about,” Ashy says, recounting the gathering of stakeholders in 1987. Ashy handed each attendee a fact sheet then addressed everyone as plainly as he could. “Now look,” he said, “you can’t say you gonna come and then get pissed off about something and say, ‘I’m done.’ You gonna have to stay the course, and you gonna have to argue your point. And we all gonna try to get along and save [the industry].

“Because let me tell you something,” Ashy continued. “I can tell you Evangeline Downs will be closed next year. I can tell you that for a fact. They already made me do projections on how to close that racetrack. We doing this to help ourselves by helping ya’ll. We want money too. If we do this, we got it made.”

With the support of Governor Edwin Edwards, riverboat casinos were legalized in 1991, followed by video poker in 1992. (Edwards later served 10 years in prison for illegal activities associated with the riverboat gambling he’d championed.) The legislation allowed for local communities to opt out and fold if they decided they no longer wanted to play by way of a simple referendum. Though video poker bolstered revenues during its first four years at Evangeline Downs, the debate among Lafayette Parish residents grew especially fierce in the mid-1990s. For centuries, the residents of Acadiana demonstrated a passion for wagering on bouree, bingo, cockfighting or horse racing, but Louisiana’s nationally reported gambling scandals left a bitter taste for some voters no longer eager to welcome people drawn to the parish by the glow of more video poker machines.

“Lafayette is an oasis in a kind of desert of gambling,” said Lafayette Mayor Dud Lastrapes, speaking out against video poker at one town meeting.

For the people of Carencro, the more troubling question was whether their venerable old racetrack could remain in business without video poker.

“A closure could cost Carencro $60,000 annually in racetrack revenue and the city’s share of video poker receipts,” warned Carencro Mayor Tommy Angelle in 1997. Money wasn’t the only thing at stake, however. Many wondered if the region’s rich heritage of horsemanship would survive without Evangeline Downs. Mayor Angelle hinted that the track had other options.

“But I understand, from a business standpoint,” he said, “that it might be in their best interest, in order to stay alive, to move to another parish where there is video poker.”

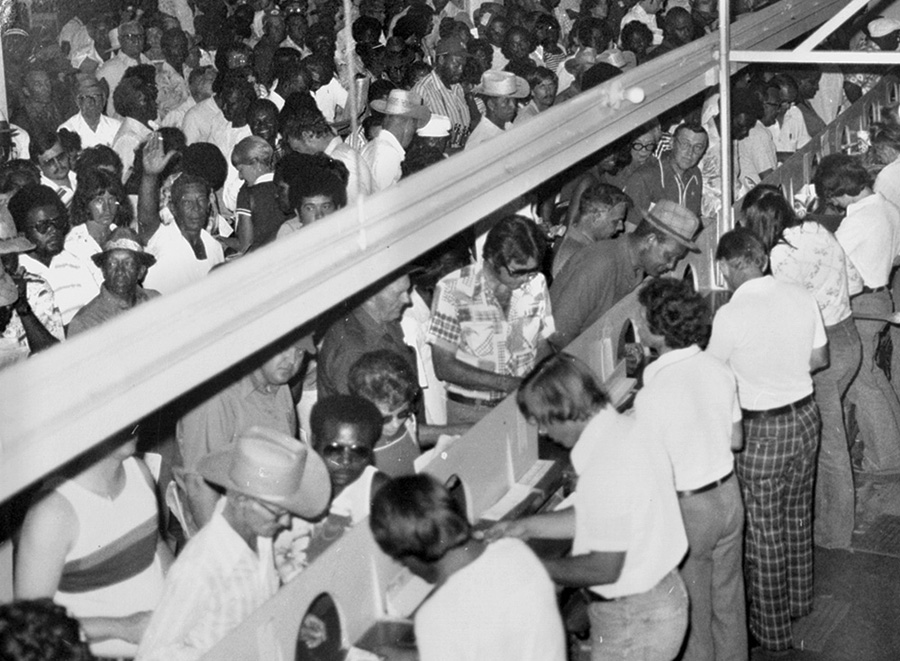

Racing fans visit the para-mutual windows on race day. The track drew gamblers from Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas who placed bets, dined in the clubhouse, and stayed in area hotels. Courtesy of the Bob Henderson Collection, Dupre Library, University of Louisiana, Lafayette

In nearby St. Landry Parish, attitudes toward video poker were a little friendlier. Sen. Donald Cravins, D-Arnaudville, was chomping at the bit to get the track moved to his parish by proposing a 200-acre facility. Costs were estimated at $30 million, and the number of jobs generated in St. Landry Parish was reckoned at roughly 1,200. The 14-mile move north up I-49 would keep the track close enough for horse racing to remain alive in Acadiana. The relocation was set in motion when Lafayette Parish voters rejected video poker in a 1996 referendum.

Immediately, Ashy started searching for a buyer and working to get the track moved.

“I went to Vegas five or six times. I knew it wasn’t going to be no problem selling it,” says Ashy. “We got a hell of a deal for the horsemen.”

In 2002, with the projected move to St. Landry Parish and the option of adding a casino that would include slot machines in place, Evangeline Downs owners B.I. Moody III and William Trotter sold the track to Peninsula Gaming and the new Evangeline Downs Casino opened on the Opelousas site in 2003. In the meantime, horse racing remained on the Carencro track through the 2004 meet while the new racetrack, grandstand, and clubhouse were under construction in Opelousas. Economic benefits in the form of increased horse racing purses and tax revenues to St Landry Parish came immediately after the Evangeline Downs Casino opened. Since 2005, all operations have been conducted at the Opelousas facility. Boyd Gaming purchased the track in 2012.

St. Landry Parish got a hell of a deal, too. According to the 2014 LSU Agricultural Summary, economic expenditures at Louisiana’s four major horse tracks topped $1.1 billion, with employment at 3,000. The news was also good for folks in the business of breeding, training and caring for horses in Acadiana. In those parishes closest to Evangeline Downs’ new location (Acadia, Evangeline, Iberia, Jeff Davis, Lafayette, St. Landry, St. Martin and Vermilion), the gross farm value of the supporting horse enterprises came to $111 million.

The community planners who dreamed of a qualifying racetrack in 1964 had set out to preserve and promote the local horse industry and its rich legacy in Acadiana. They accomplished that goal in building Evangeline Downs, and they accomplished it again in saving it. Like it or not, slots, off track betting, and video poker saved Evangeline Downs and its culture, just as they have sustained racetracks around the country.

The dark dome of the night sky over Carencro no longer flares to life at the start of the springtime racing season. And if, on an April evening, you find yourself motoring north out of Lafayette on Interstate 49, just past Prejean’s Restaurant, you might easily miss the vast, empty expanse to the east—a site currently used for equipment auctions. Nevertheless, the stadium lights of Evangeline Downs burned like a beacon for more than 50 years, drawing to it wiry Cajun bush track riders from across Acadiana and sportsmen from places much further away. You’d be forgiven if you thought you heard the melodious “call to post” of bugler John Domingue, or the echo of announcer Gene Griffin’s Il Sont Partis!

But continue driving north, toward Opelousas, and the sky gradually brightens. At the Cresswell Lane exit, the big lights again illuminate the smooth, dusty oval of the track, and fans still fill the grandstand of a new Evangeline Downs, sharing in another chapter in the long history of horsemanship in Acadiana.

—–

Alan Broussard worked at Evangeline Downs as a State Racing Commission outrider from 1973-1975 while attending the University of Southwestern Louisiana. Conni Castille is a folklorist and documentary filmmaker at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette, where she teaches film. Her award-winning films include T-Galop: A Louisiana Horse Story, the 2013 LEH Documentary Film of the Year. The authors would like to thank University of Louisiana at Lafayette’s Dupre Library Louisiana Room’s vertical files, Librarian Jean Schmidt Kiesel; editor C.E. Richard; and special thanks to Charles Ashy, B.I. Moody, III, and Dennis Herpin for their stories.