Finding Economy Hall

Remembering the politics and philanthropy that preceded the jazz

Published: February 27, 2021

Last Updated: June 9, 2023

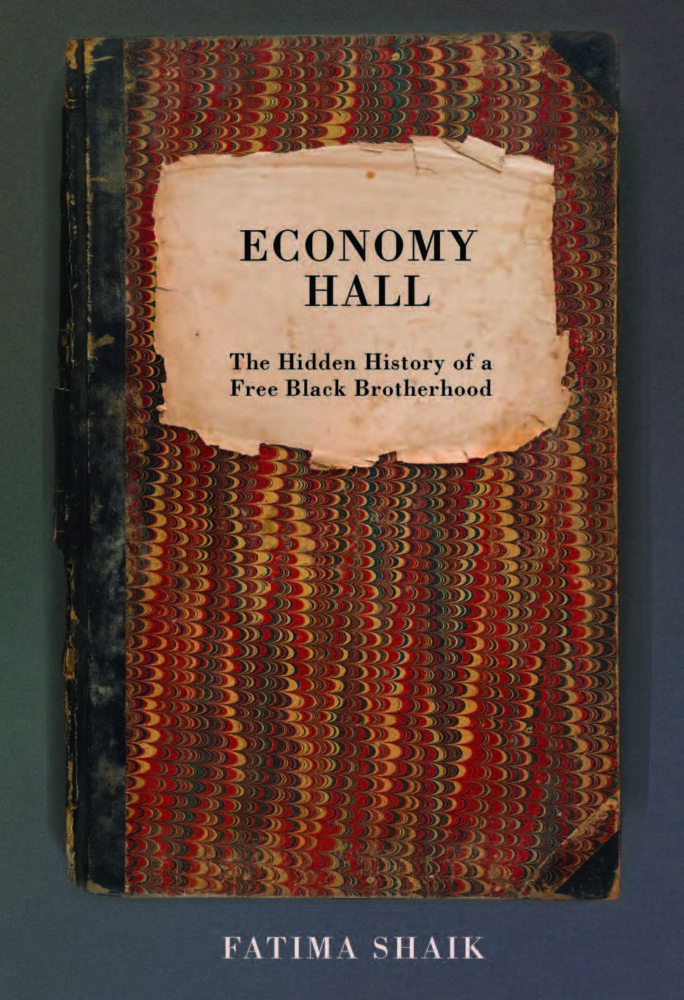

The Historic New Orleans Collection

Cover of Economy Hall, designed by Leigh Ayers from a Société d’Economie notebook in Shaik’s collection.

In February 2021, The Historic New Orleans Collection published Fatima Shaik’s Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood. Shaik grew up in New Orleans’s historic Seventh Ward, where she was nurtured and inspired by the oral histories told by her Creole family and neighbors. A trustee of PEN America, Shaik began her career as a daily journalist for the New Orleans Times-Picayune and taught for three decades at Saint Peter’s University in New Jersey. Economy Hall is her seventh book and her first work of nonfiction.

Economy Hall has a big reputation for jazz. Kid Ory’s band played there with Louis Armstrong filling for Joe Oliver one night, and Satch was hired away to the first gig that took him out of New Orleans. George “Pops” Foster compared playing the Economy to being in Carnegie Hall. One hundred oral histories in the Hogan Jazz Archives mention the hall as a location where music flowed, and everyone had a good time. But less known is a remarkable history that preceded jazz by almost a century. The radical politics and philanthropic efforts of the society that built Economy Hall touched most corners of New Orleans and some parts of the globe.

From a modest house purchased secretly by the members of the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle in 1836 to the famous Economy Hall that stood until 1965, a diverse cross-section of people came to Ursuline Street to socialize, debate, advocate, dance, memorialize the dead, and bring back some of their dearly departed in seances. Communal, political, and soulful—in sum, Economy Hall was New Orleans under a roof.

The fifteen free men of color who began the organization and the others who joined during the society’s early years reads like a roster of well-established Creoles of the 19th century: Pierre Crocker, builder and lover of Marie Laveau; Etienne Cordeviolle and François Lacroix, international tailors whose designs and real estate holdings made them wealthy; Pierre Casanave, a well-known mortician; Charles Martinez, musician, grocer, and later notary; and, my favorite, Ludger Boguille, a teacher beginning in the 1840s and important secretary of the organization.

“Creole” is the cultural term to describe these early members, although not all of their families arrived in New Orleans during its colonial period. Still, the Economistes wrote in French, styled their homes with the hybrid sensibilities of the Caribbean, shared Western European philosophies, and imbibed with New World appetites in cuisine and the arts. Their experience, however, was Black. In 1836, when the society was founded, the Economistes were segregated from banking, corporate enterprises, legal endeavors, and many other occupations that would have provided these men with a level playing field and launched them like their white counterparts into the American mainstream. They were Black, as well, because they were admirers of Alexandre Pétion, the first president of the Republic of Haiti. He eliminated the fractional designations of race—mulatto, quadroon, octoroon, and more—and embraced the word Black to describe his citizens.

In December 1857, the society built itself a new home, at 1422–26 Ursulines Street. The famous Economy Hall opened its doors nine months after the US Supreme Court declared, in its Dred Scott decision, that “Negroes, whether slaves or free . . . are not citizens of the United States by the Constitution.” Casanave, then president of the society, told the members five days before the hall’s inauguration, “May our behaviors always strike down our oppressors, so that, in each of us, our miserable enemies may discover the proof that we understand that man was born to live with his equals.”

Almost from its inception, Economy Hall became the bastion of progressive ideals in New Orleans. Economistes were members of the Equal Rights League, the Friends of Universal Suffrage, and the Radical Republicans, a party that was born in the Economy building and committed to the Black vote. The New Orleans Tribune said the Economy was “the hall where the oppressed and the friends of liberty first met in council” and continued, “Economy Hall, in New Orleans, like Faneuil Hall in Boston, like Carpenters’ Hall in Philadelphia, will belong to history.”

While some members were politically active, others worked in the community. Economistes donated to flood victims in Louisiana and émigrés to Haiti—not to mention the local nuns, poor, and infirm that they knew personally.

Working men and professional men who could be relied upon to pay dues to support the health and burial of members were admitted. Cuban cigar rollers and Mexican expats became members along with Anglo-Africans. German workers met in Economy Hall, and one of the venue’s most popular dances happened on the evening of the Italians’ St. Joseph’s Day.

For more than two decades, I have lived metaphorically inside Economy Hall—translating, contemplating, and contextualizing a century’s worth of society minutes. For even longer, though, I have belonged to the Economy Hall community. Childhood neighbors, classmates in grammar school, and longtime friends all bear names that can be traced to the society’s 19th-century membership lists. Saint Domingue refugees, Battle of New Orleans veterans, Civil War volunteers, Reconstruction officials, and political martyrs shared a common desire to teach one another and support one another’s families. In my lifetime, their descendants spent Saturdays at friends’ houses framing a new room, paid with a plate of red beans and a few beers. Or they played music at parties to raise money for the poor and for the still-segregated schools that educated their children. They politicked passionately and freely shared their honest opinions. I saw these traits forming as I read the journals of Economy Hall. For too long, the history of the Economistes was hidden, erased and forgotten by the mainstream. But for some of us, history has been repeating all of our lives. See, Economy Hall’s legacy—a legacy far beyond music—has been in plain view for those who have known where to look.