Folkloric Field Research

Documenting Louisiana’s musical heritage

Published: March 1, 2020

Last Updated: August 16, 2020

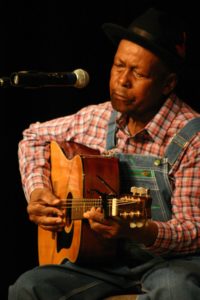

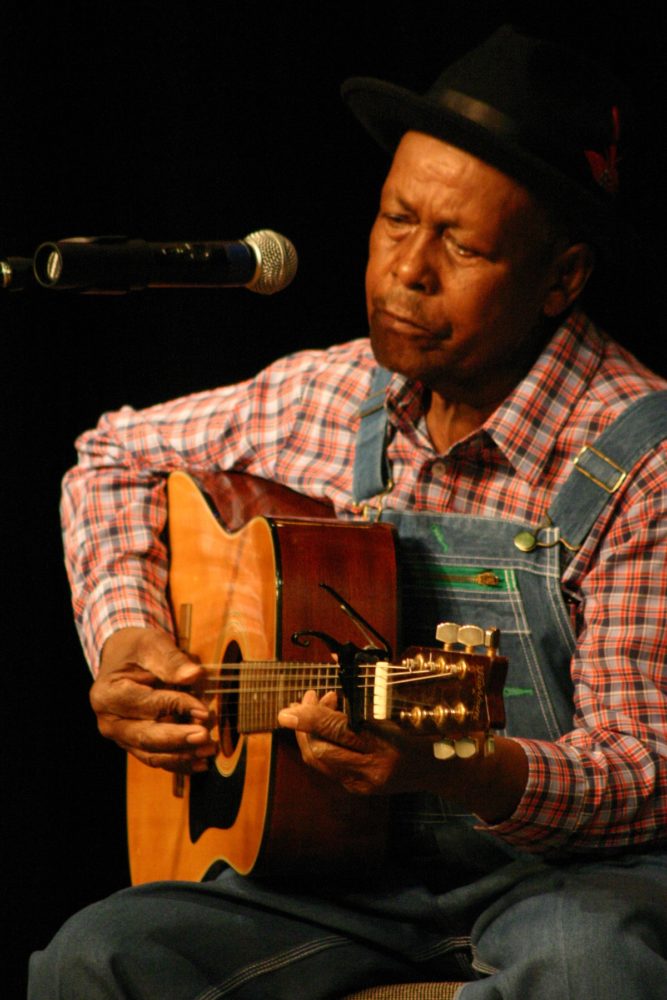

Photo by Susan Roach

Henry Dorsey performing at the Delta Music Museum in 2008.

Meanwhile the archaic a cappella ballads got on my radar via an LP released by the Library of Congress in the series Folk Music of the United States. Inspired by these initial revelations, I increasingly immersed myself in indigenous American music, the more esoteric the better. While listening I would pore over the liner notes to glean information.

From the Library of Congress album notes I learned that every song had been recorded in a far-flung location, on portable equipment, during folkloric fieldwork trips funded by the federal government. This struck me as the ultimate dream job, and likely unattainable. Perhaps subconsciously preparing for that remote possibility, however, I majored in folklore in college. Then, in 1984, Nick Spitzer—director of the Louisiana Folklife Program, now the radio host of American Routes and a professor at Tulane University—hired me to do extended fieldwork in blues and gospel. I was elated. (Subsequently I’ve also conducted field research on country music, Jewish folklore in northeast Louisiana, and the occupational lore of riverboats and oil rigs.)

My designated target area was the former Spanish colony of West Florida, now known as “the Florida parishes”: East and West Feliciana, East Baton Rouge, Livingston, St. Helena, Tangipahoa, Washington, and St. Tammany. The state-funded Folklife Program furnished me with a high-quality cassette recorder and instructed me to comb this 4,600–square-mile region over the course of six months. I had few leads beyond speculation that Hammond and Bogalusa and their environs might be fertile ground. On my first day of work I drove up US 51 to Hammond, stopping at every little store and restaurant. I would buy a Coke, start a conversation, and introduce myself as a “talent scout” rather than a “folklorist,” since that term seemed too obscure for the general public. I’d ask if there were any blues or gospel musicians in the area who played in old-fashioned styles. My fantasy was to “discover” someone who’d maintained a 1920s or ’30s sound and repertoire, as if magically frozen in time. What I found instead was just as culturally significant—interpreters of ’50s blues hits popularized by such artists as Jimmy Reed and B. B. King. In addition many interviews presented compelling oral histories and strikingly creative usages of language.

Rich interviews like those with Bridges and Cavalier made up for the tedious aspects of fieldwork, including long drives to meet musicians who no-showed, or, in one instance, had pawned his guitar.

Most of my inquiries along Highway 51 elicited blank looks, so I’d drive on with empty Coke cans clattering in my car. But one store cashier suggested that I go find a guitarist in Hammond named Otheneil Bridges Sr., better known as Hideaway Slim. (This nickname referred to the popular blues instrumental “Hide Away,” recorded in 1961 by guitarist Freddy King.) Bridges proved to be an excellent blues musician, albeit within his home only, because he had retired from performing blues in public since embracing religion. Bridges had considered a blues career but didn’t pursue it due to his spiritual ambivalence: “You got to be out there all the way,” he reflected. “[If not] you’re just climbing a slimy pole.” This was my first of many encounters with the concept of blues as “the devil’s music.”

Definitions of the blues in other interviews likewise deemed it to be a powerful force, although not always in religious terms. In a rural roadhouse near Angola, guitarist Gus “Gatemouth” Cavalier explained, “What the blues means is . . . when you get out of bed, the floor don’t feel right. You put your left slipper on your right foot, and your right one on the left, and then you might stick both your feet in ’em backwards! Oh shit! That’s the blues!”

Rich interviews like those with Bridges and Cavalier made up for the tedious aspects of fieldwork, including long drives to meet musicians who no-showed, or, in one instance, had pawned his guitar. In total I drove 2,300 miles around the Florida parishes. Following that experience I made several fieldwork trips to northeast Louisiana for the Delta Folklife Project. In Rayville, in Richland Parish, I bought a Coke and asked my usual question. Twenty minutes later I was interviewing an accomplished acoustic rural-blues guitarist named Henry Dorsey. Somewhat surprisingly, Dorsey, a farm laborer, had never performed in public. The interview resulted in Dorsey and his harmonica-playing partner, Wayne “Tookie” Collom, appearing at the Louisiana Folklife Festival and other events around the state. This underscores the point that field research can result in direct economic benefit to local communities.

In Vidalia, in Concordia Parish, I met guitarist Gray Montgomery, who folklorists would describe as a “songster” due to his extremely eclectic repertoire. Montgomery was equally adept at blues, classic country, cowboy songs, pop hits, surf music, rockabilly, and more—whatever his nightclub audiences preferred for dancing. He was quite a raconteur, too: “Jerry Lee Lewis used to be my drummer [circa 1950]. We had a Friday–night gig across the river in Natchez, Mississippi, and every time Jerry Lee’d be late. The owner [would say] ‘Jerry, where the hell you been?’ and Jerry would answer, ‘Well you know I live way over yonder in Ferriday.’ Somehow that excuse always worked.”

My most recent interviews focused on Cajun music, zydeco, traditional jazz, and country, for the Baton Rouge Folklife Survey in 2015. I still find it a thrill to do fieldwork. And I strongly believe that many more fine traditional musicians can still be found and documented throughout Louisiana.

The Florida Parishes Project and Baton Rouge Folklife Survey interviews are in the Louisiana Folklife Collection at the LSU Libraries in Baton Rouge. The Delta Folklife Project interviews are in the Louisiana Tech Folklife Collection in Ruston. Special thanks to folklorists Maida Owens and Susan Roach.

Ben Sandmel is a New Orleans–based writer, folklorist, producer, and the former drummer for the Grammy-nominated Cajun/Western swing band The Hackberry Ramblers. In May 2018, the LEH honored Sandmel with an award for his Lifetime Contributions to the Humanities. In January 2020 the Folk Alliance International honored Sandmel with a Spirit of Folk Award.

Sound Advice is funded in part by a grant from the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation.