Magazine

Friends of the Farmers

A statewide coalition bolsters access to fresh, healthy food by training and funding farmers

Published: May 30, 2025

Last Updated: August 29, 2025

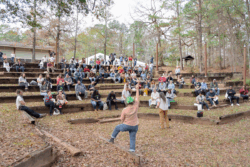

The Louisiana Small Scale Agricultural Coalition’s 2025 Climate Convening at Chicot State Park in Evangeline Parish.

Photo by Jen L. Rogers, courtesy of Shreveport Green

Severe weather moved over Chicot State Park one evening last January, prompting the Louisiana Small-Scale Agricultural Coalition (LSSAC) to cancel the second day of their new signature event. The LSSAC is a statewide network supporting farmers of specialty crops who operate on a hundred acres or fewer. The event organizers were heartbroken, but validated too. “The winds started getting high and power went out and things started happening really fast,” said Lauren Jones, executive director of coalition member Shreveport Green. “It was a prime moment to see our ability to work together. I got to see the way a bunch of farmers function, and in a weird way, that was the coolest part.”

LSSAC initiated its annual gathering, called the Climate Convening, out of a realist’s understanding that rough weather will continue to thrash Louisiana. The long drought in summer 2022 brought to fore the needs many farmers had in the face of intensifying weather events. “We saw how many farmers were losing crops because they didn’t have irrigation. They were not prepped for a scenario like this, and the capital that was required for them to purchase a pump, dig a well, and put in drip irrigation, even by extensive systems of hoses or cisterns, was not something that they had planned for,” said Marguerite Green, then co-director of SPROUT NOLA and current director of producers for Louisiana Food Policy Action Council. “It was impacting the entire food system. It was impacting each of the markets that’s part of LSSAC, which then impacted so many eaters in our community.”

LSSAC first came together through a federal program that required technical-assistance partners in each region of the state. These organizations include SPROUT NOLA, BREADA, Shreveport Green, Acadiana Food Alliance, Louisiana Central, Market Umbrella, and New Orleans Food Policy Action Council. Their adjacent, often overlapping, missions seek to improve Louisiana’s food systems, focusing primarily on the farmers who produce the food.

“I think a lot of what’s brought LSSAC together is focusing on how climate is a crisis”

SPROUT NOLA provides technical assistance to farmers and lobbies for agricultural policies in state and local government. BREADA (Big River Economic Development Authority) organizes farmers’ markets in the Capital Region. Shreveport Green promotes a deeper connection with nature and is responsible for multiple urban farms in the city. Each group has seen its efforts evolve over the years. Their increasing similarities have resulted, to some leaders’ eyes, in competition for the same pot of money. “But we’re starting to see a change happen across the nonprofit sector,” said Jones. “There’s a generational movement to better communicate and share our experiences. Instead of working in silos, we’re trying to create an efficient system. We don’t have as much need for a major amount of money into one organization. We can make the impacts deeper, and I find we all have extra piece to give.”

“There was already a lot of crossover with our constituency, so it just made sense that we could connect in a formal level as organizations so that we were providing coordinated technical assistance and resources,” said Darlene Rowland, executive director of BREADA. “It makes a more unified approach to the farmer that we’re working together as one statewide organization to roll out these resources, and they know they can get the same answer from whoever they’re talking to in the local food system as on a statewide level.”

“We started to realize that by working together across sectors, but all still within agriculture, we were just able to provide better services to farmers,” said Green. “It mirrors patterns in nature. We’re building a more robust food system in Louisiana as we acknowledge how multidimensional that system is.”

Beyond providing resources, LSSAC also works to educate farmers on their responses and responsibilities in the changing climate. This year, the coalition sponsored a six-week disaster preparedness program called Don’t Get Caught With Your Plants Down, with webinar topics ranging from how to get a farm number from the federal Farm Service Agency—essential for accessing recovery resources and loans—to documenting crops and securing a farm site. “We’re making those linkages for farmers between climate and industry . . . [showing how] growing practices are changing and the environment and climate are impacting their farms. I think a lot of what’s brought LSSAC together is focusing on how climate is a crisis, [one which] farmers have a lot of power to slow and mitigate through their actions,” said Green.

The inaugural Climate Convening in 2024 brought together farmers from across the state for panels on subjects including disaster preparedness and crop costing; it also featured locally grown food (of course), music and bonfires, and opportunities for networking. It’s the last item that first-generation farmer Sarah Roland appreciated the most. “People don’t realize how isolating it can feel to be a farmer,” said Roland.

She began her Bayou Sarah Farms in 2019, raising chickens for slaughter. In 2020, she pivoted to water buffalo, from whose output she makes cheese and ice cream for direct sale to consumers. Her popular community-supported agriculture (CSA) box also includes organic blueberries, honey from her beehives, and eggs. The early days of starting her farm “felt like I was reinventing the wheel,” said Roland, who appreciates the training resources she sees LSSAC now providing to novice farmers, as well as the state and federal grant opportunities to which the coalition alerts her. “I’d love to have those grant opportunities in one place,” said Roland, “in case I miss an email.” (The LSSAC website indicates such a directory is on the way.)

The uncertainty with federal funds under the Trump administration has only galvanized the LSSAC leaders, who can’t lose time to political whims when the climate is changing for the worse and aging farmers are not being replaced by a younger generation. According to the Louisiana Food Bank, one in seven Louisiana residents can’t provide healthy food for themselves or their household. “We’re trying to create stability through collaboration,” said Green.

LSSAC has diversified their funding network, drawing in private dollars from the likes of Danish pharmaceutical company Novo Nordisk, and hopes to entice more residents to join the fight for Louisiana’s food sovereignty. “I think we consider ourselves an agricultural economy because historically we have been, and because there are so many other kinds of agriculture that are so important to our state’s economy,” said Green. “But in terms of the actual food that’s on our table, so little of it is grown in Louisiana. It is a deep belief of everyone in LSSAC that we care a lot about food security, hunger, and nutrition, and we’ve identified that the best way to show our support is by making sure there’s abundant fresh food in Louisiana, and that it’s accessible to people.”

“It’s reassuring to know that when we’re all in this same place together, we can act accordingly,” said Jones, recalling the cancellation of the Climate Convening. “There was no panic, no freak out. We were able to roll up the tents together. We were able to say, ‘okay, I’m going to do this. You’re going to do that. We’re going to go in here and take care of the food.’”

Lucie Monk Carter is a writer and photographer in Baton Rouge.