Glitter and Be Gay

A gay Mardi Gras krewe shines in Acadiana’s capital

Published: December 1, 2019

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Jonathon Silver Ahhee

Krewe member Jacque Rowe at Apollo’s Bal Masque XLIII in 2019.

Grow up and move to the city.” This is the advice most queer people get at some point in adolescence, from a trusted adult, the internet, or their own instincts. Even in recent years, with greater public acceptance, openly gay life is still often thought of as a metropolitan phenomenon. Take a bus to San Francisco, hitchhike to New York, go to college in New Orleans: the city’s where your real life can begin. But a far-from-trivial number of queer people bloom right where they’re planted: they grow up, come out, and stay put, building complete and happy lives in the smaller cities, towns, and rural stretches of the country.

Lafayette has 125,000 residents in the city proper and 450,000 in the metro area, but Louisiana’s fourth-largest city has maintained, and even nurtured, a small-town vibe as it’s grown, developing trendy pockets that rival the hipster redoubts of New Orleans. (Of course, not everyone in Lafayette agrees that it still feels like a small town; more than one person has told me that “you can’t ride your horse downtown anymore.”) It may seem counterintuitive that this Catholic city with its everybody-knows-everybody tight-knittedness would be host to the longest-running gay Mardi Gras krewe outside New Orleans, but it shouldn’t come as that much of a surprise: Acadiana loves Mardi Gras, gay culture has embraced pageantry, and the two tendencies, joined in the Mystic Krewe of Apollo de Lafayette, put on a rhinestone-studded annual ball that’s a highlight of the Lafayette calendar.

Mardi Gras has always featured aspects especially appealing to queer people: the overturning of norms, the opportunity to present oneself however one wishes, the de rigueur application of glitter. For decades, in an effort to combat “vice,” New Orleans outlawed cross-dressing—a decision one can imagine annoying the city’s pantalooned patroness, Joan of Arc. The city excepted only Mardi Gras day (and, later, Halloween); enforcement of the ban petered out in the early ’70s. Mardi Gras was a day, often the day, when queer or gender-nonconforming people weren’t “odd”—and weren’t subject to potential persecution. The idea of publicly sanctioned subversion attracted, and continues to attract, people who usually have to pretend to be “normal”—once a year, “normal” goes out the window, and what is ordinarily condemned is celebrated.

Private gay krewes emerged in the late ’50s and early ’60s, providing gay men the opportunity to socialize as couples, some in drag if they wished, and to participate in some of the Mardi Gras traditions celebrated by straight krewes without having to remain in the closet. (Lesbian and mixed-gender queer krewes arose later.) New Orleans’ relaxation of its anti-transvestism law came too late to save the Krewe of Yuga (pronounced “you gay” by those in the know), the first recorded gay Mardi Gras krewe, whose private party was raided by police in 1962. (At the police’s arrival, the queen ran into the nearby woods to hide in a tree; alas, the cops’ flashlights caught the beads on his gown, and he was dragged to the hoosegow.) Other gay Mardi Gras groups formed, some flashes in the pan and some building long traditions, before the arrival of Roland Dobson. Dobson, who is never referenced without a comment on how very handsome he was, had made the gay migration from Bogalusa to New Orleans, and as he made his mark on New Orleans society brought a very American concept to the world of Mardi Gras krewes: franchising. Apollo, the gay krewe he founded in New Orleans in 1969, developed branches in Baton Rouge, Shreveport, Birmingham, Dallas, Memphis, and, in 1976, Lafayette. Some of these branches, including the New Orleans one, were unable to sustain themselves, left behind by changes in gay culture and hollowed out by the ravages of AIDS; those who didn’t succumb to the epidemic themselves often reallocated their resources and attention toward care for ailing friends and partners. The Lafayette chapter, along with those in Birmingham and Baton Rouge, is still going strong after more than forty years and, delightfully, will bring the torch back to New Orleans: John Bertrand, the Krewe of Apollo de Lafayette queen in 2017, is restarting the New Orleans chapter, with the first ball planned for the 2020 Carnival season.

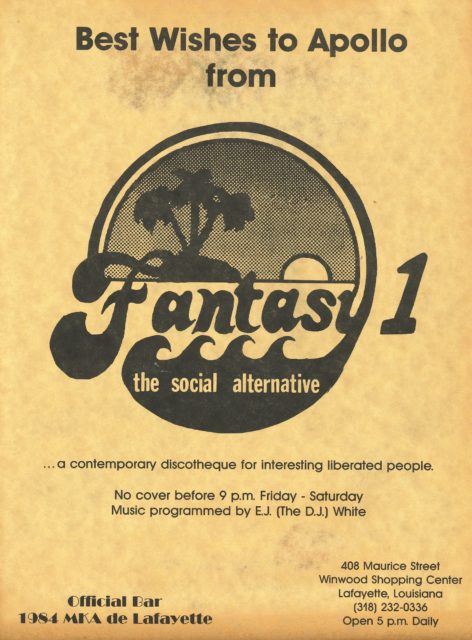

Apollo’s programs have often run ads from local businesses, not all of them as intriguing as this 1984 discotheque ad. Courtesy Ted Viator

I met three krewe members at the krewe’s warehouse and workshop on the south side of Lafayette. The workspace is colossal, with an enviable amount of storage space holding boxes labeled “feathers” and “lamé (misc.).” Ted Viator and Billy Evans have been in the krewe since its early years (Evans was one of the six founding members); Darrell Frugé, the current captain, joined about twenty years ago. “Miss” Jimmy Pool, a member since the first year, was unable to join us, but he continues to play a featured role in the annual ball: he greets guests at the entrance, adorned in a glittery phallic headdress or in drag complete with improbable bosom. This greeting sets the tone for the evening, loosening up attendees who might be nervous in a gay space and warming the audience up for the bawdy, besequinned show to come.

All the men are from Lafayette or the broader area, and all described welcoming attitudes in the region, with Viator gently ribbing Evans about having been “born out of the closet”—meaning his sexuality had not surprised those who knew him—and referencing his own experience as an open member of the krewe in the ’70s, just after he finished high school: “[A story on the ball] was in the paper the next day, and no one said anything.” In early years, some members were reluctant to be photographed at krewe events and identified openly with a gay organization; today, not only are most members proudly open about their gayness and their participation in the krewe, but some members also consider the ball a business networking opportunity. Viator, a landscape architect, and Frugé, who works in oil and gas, both mentioned inviting clients and other business contacts. These guests enjoyed themselves and were pleased to be invited, as well they might be: tickets can sell out quickly.

Apollo has held their ball at the Cajundome, Blackham Coliseum, and even the Yambilee Fairgrounds in nearby Opelousas; they also contribute floats to Lafayette Mardi Gras parades and volunteer as concession workers at Lafayette’s Festival International. This access to public spaces showcases the community’s willingness to open venues and events to a gay group and also testifies to the cultural heft of the krewe: Apollo de Lafayette can pack a stadium and line a parade route with attendees. Frugé pointed out that this public acceptance doesn’t mean no one in town disapproves—but it does mean that the disapproval lacks any apparent mechanism to hamper the krewe’s successes. One striking measure of the krewe’s acceptance in the wider community is their habit of “borrowing” bodybuilders from local gyms to serve as eye-candy ushers and the muscle to push the ball’s floats on their tour around the venue. These men, predominantly straight, enjoy the experience (and the attention)—after all, they get a free entry to one of the best parties in town.

The members I spoke to felt that the quality of their work was an important part of the group’s having been broadly accepted. The costumes are grander (“we have big accessories, not little ones like in New Orleans”) and the show longer and livelier than most other krewes provide. Krewe of Apollo doesn’t just put on a good show, it puts on a good Mardi Gras show, and that helps anchor the organization and its members in the local community and culture.

Frugé also noted that Apollo had given local people the opportunity to see that gay men were just like everybody else—though only in South Louisiana would putting on a lavish, shimmering ball complete with ten-foot-high costumes make a group of people seem normal. The visibility—not just of gay men, but of happy, fulfilled gay men active in a civic organization and eagerly building on cherished local traditions—may have a particularly strong effect in a smaller community, Viator noted. He spoke of an acquaintance who had suspected her son was gay; among other clues, he would stash the fancy Christmas decorations she made in his bedroom (“Gold lamé is always a giveaway,” said Evans). Viator’s visible status as a content and successful gay man, exemplified by his participation in the krewe, made his acquaintance feel safe in approaching him for advice about whether and how to address the issue with her son. The lamé-loving boy is now an out adult in Atlanta.

By participating in Mardi Gras—and by doing so unapologetically and excellently—the Krewe of Apollo de Lafayette affirms a right for gay people not only to assemble privately and enjoy their own traditions but also to participate in the celebrations and rituals of the wider community. Young gay men in Acadiana can look forward to joining the Krewe of Apollo when they get old enough, and older members can look back on decades of work for gay acceptance that they accomplished while they were also having fun. The MC of the Krewe of Apollo’s ball always ends the kickoff of the festivities with “sit back, relax, and be gay.” Apollo shows the best sides of community—both community based on shared values and community based on shared geography and culture—and the krewe has made Lafayette a little more relaxed, a little more gay, and a little more complex than you might think.

Chris Turner-Neal is the managing editor of 64 Parishes.