Magazine

The Glorious Eighth of January

January 2015 marked the 200-year anniversary of the Battle of New Orleans

Published: January 7, 2015

Last Updated: May 3, 2019

Following the Civil War, public enthusiasm for the battle’s anniversary diminished as the number of surviving veterans of 1815 declined and New Orleans coped with the struggles of Reconstruction. By the 20th century the Chalmette battlefield was emerging as the location where the memory of the battle was preserved and commemorated, which further eliminated the need for the civic rituals that had once served this same purpose and been carried out on the city’s streets. The first half of the 19th century was therefore truly the golden age for the battle’s anniversary, when people gathered and frolicked in the city as they would on any holiday, and the history of the annual celebrations during this time is arguably as compelling as the history of the battle itself.

The historical memory of the Battle of New Orleans has long suffered from the misperception that it was a pointless engagement because the Treaty of Ghent had already been signed. Informed scholars and aficionados of the War of 1812 recognize that while the Treaty had been signed, it had not been ratified, and so the war technically was not over when the battle was fought. Recent studies have also brought to light the greater social and cultural significance of the battle, especially how the glory of the victory helped heal the wounds of an unpopular war and propel a new sense of nationalism. For Louisianians, the timing of the battle had never detracted from its significance because what made the battle meaningful was what it symbolized in terms of Louisiana’s incorporation into the United States.

Following the Civil War, public enthusiasm for the Battle’s anniversary diminished as the number of surviving veterans of 1815 declined and New Orleans coped with the struggles of Reconstruction.

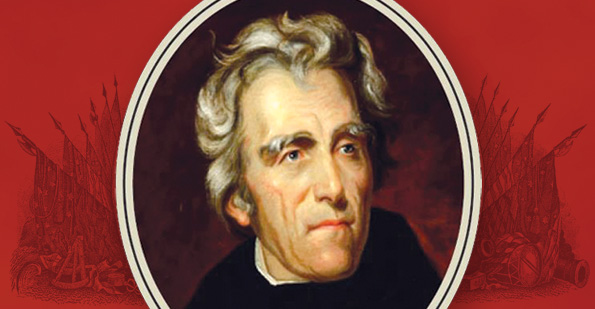

Prior to the battle few outside of Louisiana had anticipated that the state’s inhabitants had developed enough of an attachment to the United States to be willing to defend it against a British invasion. Negative depictions of the state of local defenses and of the disaffection of the local populace prior to Gen. Andrew Jackson’s arrival in December 1814, however, ultimately added to the battle’s dramatic outcome. Reports of the victory shocked the nation not only because of the disproportionate number of casualties on either side, but also because of who had accomplished this feat. The victory instantly eradicated skepticisms about Louisiana’s political bond with the rest of the nation and evoked an outpouring of public praise for the state’s inhabitants. The Niles Weekly Register, a nationally circulated newspaper, declared that the battle had dispelled “all those feelings of distrust and jealousy” towards Louisiana. Another letter to the Niles’ editor summed up the change that had occurred by simply referring to the once scorned state as “Sister Louisiana.”

Louisianians were well aware that there was widespread skepticism about their attachment to the U.S. before the battle, and so the victory and national praise that followed was a source of tremendous pride that signified the triumph of Louisiana’s political integration. Since the Creole and older populations of New Orleans could not claim any of the glory of the American Revolution, the defeat of the British compensated for this by proving the merits of citizens who had undeniably earned their membership within the republic. For decades after the victory and precisely for this reason, the inhabitants of New Orleans celebrated the battle’s anniversary with the kind of fervor shown elsewhere in the nation on the Fourth of July. The Battle of New Orleans had defined the city and so too would the local enthusiasm for the Battle’s anniversary.

It was Jackson who requested that a “ceremony of solemn thanksgiving” be held on January 23, 1815. This was not an unusual request. The practice of designating a day for the public expression of thanks in the aftermath of a military victory was common in cities throughout the U.S., especially in the northeast following the successful battles of the American Revolution. By requesting that the inhabitants of New Orleans conduct a similar ceremony, Jackson was not just following cultural protocol, he was also connecting the memorialization of the victory in New Orleans to a national historical consciousness of American military triumphs.

French painter Lami depicted the American Victory of over the British at the Battle of New Orleans, fought just outside the city in St. Bernard Parish on January 8, 1815. Courtesy of the Collections of the Louisiana State Museum, 1991.080

It was the elite white women of the city who undertook the responsibility of organizing the ceremony of solemn thanksgiving, which was by far the most dramatic public event that had ever been held in New Orleans. The general format of the ceremony featured all of the typical components of a civic military celebration—a triumphal arch, a martial procession, and a speech delivered by a well-respected religious authority—as well as a few unique artistic flourishes that reflected the local perspective on the battle.

The central staging of the ceremony’s pageantry took place in the Place d’Armes (later renamed Jackson Square). In the middle of the square stood a large arch covered in laurel wreaths, a traditional symbol of martial victory. Garlands of laurel wreaths linked this arch on either side to the entrance of the square and were supported by eighteen pillars, nine on each side. Each pillar had been decorated by more wreaths and on each a medallion had been placed bearing the name of the 18 states. A young lady dressed in a white gown stood by every pillar. On their heads the women wore veils tied by a white satin ribbon and adorned with a single golden star on the left side. The ladies all held white baskets trimmed in blue ribbon and filled with flowers. The four states that had played a prominent role in the battle had white silk banners attached to blue and white staffs positioned by each pillar. These banners all bore mottos in large gold letters that acknowledged what each of these four states had contributed to the victory: Louisiana—glory and safety, Mississippi territory—valor and generosity, Tennessee—Jackson and his heroes, Kentucky—bravery and patriotism. Beneath each side of the main arch there were two little girls that stood on pedestals in order to hold laurel wreaths over Jackson’s head as he passed under the arch. Two other young women also stood on each side of the main arch in costumes symbolizing Liberty and Justice.

The victory instantly eradicated skepticisms about Louisiana’s political bond with the rest of the nation and evoked an outpouring of public praise for the state’s inhabitants.

The entire square and streets leading to it were filled with spectators as were the balconies and windows of all the adjacent buildings. The white Creole uniformed militia companies under the command of Major Jean Baptiste Plauché, were stationed in lines along the levee to greet the general and his officers and staff as they passed through the city to the Place d’Armes. A military band saluted Jackson and his men as they approached the square. Upon his arrival, the young lady who represented Louisiana read a message of thanks to the general that had been composed by a woman in the city. As Jackson processed through the square the women by the pillars threw flowers in Jackson’s path and then came together in pairs from the pillars, joined hands, and followed Jackson up to the cathedral entrance. Once at the entrance the Abbé Dubourg gave an address extolling the general’s virtues as a military commander and exclaiming how Jackson’s presence was the blessing the Almighty had bestowed upon the city to save it from the enemy. Jackson gave a brief response thanking the Abbé for his kind words and expressing his appreciation for the men who fought. Once in the cathedral a traditional hymn of praise, the Te Deum, was sung and a concert given of music especially composed for the occasion.

The elaborate pageantry of the battle’s inaugural commemoration showcased all of the sentiments of pride and appreciation that were to be expected in the aftermath of a military victory. The purpose of the ceremony, however, went far beyond the public display of communal joy. In her study of how certain civic ceremonies in New Orleans served as venues for publicly negotiating political conflicts during the 19th century, historian Sandra Frink argues that the the ceremony was meant to “elevate the status of the white Creole soldiers over all others in the battle.” The American forces that fought under Jackson were infamously diverse: Baratarian privateers, Tennessee and Kentucky volunteers, Choctaw Indians, and two main battalions of free colored militiamen all had joined together with U.S. Army regulars and white Creole militiamen to defeat the British. Yet, as Jackson made his triumphant march through the city to the Place d’Armes it was only the white Creole militia that stood along the levee to greet the general. By focusing attention on the white Creole militia and Jackson, city leaders sought to direct public gratitude in ways that reaffirmed the existing social and political hierarchy. This was critical specifically because of the inclusion of free men of color in the city’s defense.

Although whites in New Orleans had relied on the services of a free colored militia since the city’s founding, they had long resented and worried about the existence of the free colored militia. After the Louisiana Purchase, the territorial legislature had tried to eliminate the free colored militia, but the War of 1812 and the British invasion in 1814 had necessitated the reinstitution and expansion of the free colored militia. One of the reasons that white leaders had opposed the free colored militia was that they feared that military service would inflate the self importance and communal stature of free men of color. During the battles the free colored militias had proven to be equally as valorous as the white militias and military so the immediate public distancing of the free colored battalions during the battle’s inaugural celebration sent a message about who those in power locally hoped to channel public appreciation towards. Over the course of the next 36 years the free colored veterans continued to be excluded from the commemorative rituals enacted on the battle’s anniversary, which ensured that the white veterans retained their position as the public face of Jackson’s valiant forces.

The lionization of the white Creole forces was further reinforced by the role that the city’s elite white women and girls played in the ceremony. As the engineers of the ceremony and its principal participants, women established themselves from this early moment as the conservators of the battle’s memory. The central place that women occupied in the ceremony, however, was intended to amplify the fact that the custodians of female virtue had done their jobs. As one historian, Mary Ryan, has shown in her comparative study of parading and civic celebrations in the 19th century U.S., women often served as “abstract emblem[s] of male power and authority” and were included in such ceremonies specifically for this reason. The prominence of young white women on New Orleans’ day of thanksgiving took on even greater meaning as a reflection of local white male honor and strength because of the fears that had circulated in the city following the British assaults in the Chesapeake in 1813. During this campaign reports that the British had engaged in ruthless physical and sexual violence prompted local anxieties about what would happen if the British managed to reach New Orleans. The need to prevent a similar turn of events was one of the sources of motivation that Jackson drew upon on the eve of battle to encourage the citizens of New Orleans to fight bravely. The British never made it to the city, and so the prominence of white women in the ceremony of thanksgiving, along with the racial exclusivity of the event, focused public attention and praise from the beginning on the men who, as white slave-owning patriarchs, supposedly bore the responsibility of maintaining security and stability in a slaveholding society.

After the ceremony of thanksgiving, the state legislature resolved that every year on January 8th the victory over the British was to be honored as a holiday and commemorated with a parade that involved the city and state’s most important civil, military, and religious representatives. In fulfillment of this resolution on the first anniversary in 1816 various civil and military authorities as well as officers of the U.S. Army and Navy joined in a procession from the Government House to St. Louis Cathedral for the chanting of the Te Deum. During the singing that year, the 1st regiment of U.S. Infantry fired several musket volleys that were answered by cannon shots fired from Fort St. Charles and ships in the river. Following the official ceremony of the day, the Louisiana Courier reported that “all the inhabitants of New Orleans gave themselves up entirely to pleasure—dances, banquets, nothing was spared.” The Courier then proclaimed how “it is to be wished that that day be thus celebrated every year.” This wish was granted as both the official and unofficial repertoire of activities continued to grow in subsequent anniversaries.

There are some indications that the merriment of the day could lead to overly rambunctious behavior among the populace as the local papers made a habit of noting whether an anniversary had passed without incident or not.

The Battle’s anniversary quickly became a full day of revelry for the city’s inhabitants that started early with crowds gathering on the streets in anticipation of the parade. Once the formal rituals of the civil and military procession, artillery salute, and singing of the Te Deum had ended there were always special events and functions held in honor of the day. Concerts featuring music composed for the occasion were common, and, of course, an array of balls were always thrown to help carry the celebration into the night. Some years there were more unusual attractions such as in 1817 when a circus in town offered a viewing of an “exact representation of the battle fought on the 8th of January.” “This presentation,” the advertisement announced, “will be seen in a large transparency comprehending twelve or fourteen hundred persons and the camp of General Jackson.” The circus performances that evening then commenced with a show of military maneuvers, grand feats of horsemanship, and a fireworks display.

There are some indications that the merriment of the day could lead to overly rambunctious behavior among the populace as the local papers made a habit of noting whether an anniversary had passed without incident or not. In 1823 the Louisiana Gazette reported that one of the concerts had been well attended and that “if many ladies did not grace the boxes [of the theater], it can only be attributed to their apprehension of witnessing some of the disorders which often occur after a day of public rejoicing.” If it wasn’t the demeanor of the crowds that caught the attention of the local press, at times a quirky or unexpected occurrence would distinguish a particular anniversary, such as in 1823 when a Tennessee horse named Jackson that was owned by a Mr. Jackson took the purse at the races that day.

While the assortment of performances and social events in the evenings varied from year to year, the main attraction of the day gradually transformed as well. By 1824 a committee had formed for the purpose of “arranging the mode of celebrating the festival of the 8th of January,” which helped the official commemorative ceremony take on a more organized and formalized quality. This year the Louisiana Gazette published the plans for the anniversary the day before, presumably to educate the public about some of the changes the committee had made. One new addition was the delivery of an oration by a local lawyer, Thomas F. McCaleb. In the years that followed other community, state, or military leaders would assume the honor of giving the oration, which sometimes was reprinted in the local papers to ensure that the public had the opportunity to savor the patriotic sentiments routinely expressed in such speeches.

Throughout the antebellum era public interest in the annual battle ceremonies was usually contingent upon such incidental issues as the weather. Cold, dreary, wet days usually contributed to a smaller public turnout, whereas mild, brilliantly sunny days brought the public out in droves. Public enthusiasm was also influenced by the coinciding visit of a military hero. Gen. Lafayette’s visit in 1825, Jackson’s visits in 1828 and again in 1840, and Gen. Winfield Scott’s visit in 1859 all helped make the anniversary celebrations those years especially popular. The involvement of a special guest gave the day’s activities fresh appeal, which went a long way toward invigorating public enthusiasm and distinguishing a particular anniversary.

Of all the changes that the battle’s anniversary rituals underwent in the antebellum period, none were as dramatic as the sudden inclusion of the free colored veterans in the 1851 parade. Although most of the men were quite elderly, 90 free colored veterans marched at the front of the procession that year with the white veterans, the governor, various state and military dignitaries, and city leaders. In comparison to the 25 white veterans who were present, the collection of free colored veterans presented quite a remarkable spectacle for the crowds of observers, and their presence in the parade marked a profound turning point in the free colored veterans’ struggle to keep the memory of their participation in the battle alive.

It was extremely rare for African Americans to participate in white organized public rituals in any part of the U.S. at that time, and the public honoring of black military veterans outside of black communities simply did not occur. Yet, after being excluded from the official anniversary ceremonies for 36 years and in the midst of a surging anxiety about the status and power of free people of color in New Orleans, civic leaders embraced the inclusion of the free colored veterans. The answer as to why this sudden reversal occurred is revealed when we look outside of Louisiana to the campaigns that were emerging during the antebellum era among anti-slavery activists, abolitionists, and intellectuals seeking full, equitable citizenship for all free African Americans. Examples of black military service were at the center of these campaigns because of the evidence they provided of free men of color’s patriotism and abilities.

Highlighting the sacrifices of black soldiers also exposed the hypocrisy of denying equal citizenship to individuals who had been expected to provide equal service in times of national need, and there had been no African American forces as well known for their valor than the free colored militia at the Battle of New Orleans.

As the memory of the free colored militia’s service and the remaining veterans emerged through these campaigns as national symbols of equality, white leaders in New Orleans responded by allowing them to participate in the anniversary ceremonies. This was a strategic effort to build alliances with the veterans while redirecting the public notoriety the veterans had gained in ways that reaffirmed the existing slave regime and three caste social order. In their reports on the battle anniversary celebrations in 1851 several local newspapers provided a justification for the veterans’ inclusion that would be palatable to nervous white onlookers and that would draw attention to the fact white slaveholders were—unlike northerners—willing to publicly honor free men of color. The papers made a concerted effort to emphasize that the veterans were men who displayed the most admirable—and non-threatening— character qualities. The Daily Picayune commented on the “respectability of [the free colored veteran’s] appearance” and the “modesty of their demeanor.” After taking note of their “aged forms,” the article declared how “beneath their dark bosoms were sheltered faithful hearts susceptible of the most noblest impulses.” The newspaper then expressed the hope that the presence of the free colored veterans in the parade would “produce an extremely salutary effect” on that portion of the population. In cultivating an identity for the veterans that would make their public presence and reverence acceptable to a white audience, the papers were also sending the message to other free people of color that if they wanted to preserve their liberties they should emulate the qualities literally embodied in the free colored veterans.

The free colored veterans continued to be a part of the anniversary ceremonies throughout the 1850s. By the end of the decade the city had even begun providing a carriage for the veterans to ride in during the parade—a gesture of respect that was rarely extended to free men of color. The new momentum behind the 18 veteran free men of color brought one particular individual into the spotlight more than any other: Jordan Noble. As a young teenage drummer Noble had come to New Orleans with the U.S. army and was known for leading Jackson’s forces into battle with his drum. Like many other free colored veterans, Noble volunteered for service in other wars after the Battle of New Orleans. By the 1850s he had acquired quite an impressive military record having served as a drummer in 1836 in the Florida War and in 1846 during the Mexican War. When the veteran free men of color began making more public appearances, Noble emerged as their most celebrated member. Throughout the 1850s and well into the late 19th century Noble played his drum—the same drum he played on the Chalmette battlefield—at countless events and public ceremonies. Crowds loved to gather to hear “Old Noble,” as he became known, play the reveille he played for the troops on the morning of the January 8th battle.

Noble’s musical abilities made him a familiar, endeared public figure who, like the other free colored veterans, could be depicted as representing no political threat to white authority. There is evidence, however, that Noble was not devoid of political aspirations. In August 1854 Noble attended the National Emigration of Colored Men meeting in Cleveland, Ohio. This particular conference brought together men of color who supported emigration out of the United States, but who rejected the idea of leaving the Western Hemisphere. Enthusiasts of emigration within the Western Hemisphere posited that by remaining in closer proximity to the U.S. they could be more effective in their campaign to bring an end to slavery in North America. Noble and three other free men of color from New Orleans acted as the delegation from Louisiana at the conference. and he was elected to serve as a commissioner for the state. It is unclear whether Noble fulfilled his obligations as a commissioner or if he ever attended any of the successive conventions of the National Emigration of Colored People’s organization. Nonetheless, through his involvement with this group Noble had interacted with some of the most radical political thinkers of his time who were staunchly committed to the attainment of full political, social, and economic equality for all African Americans. Old Noble, it seems, was not content with the subservient place of African Americans in the U.S. after all. For most African Americans in the South the opportunity to occupy a public role as a soldier was nonexistent until after the Civil War, but because of national notoriety of the Battle of New Orleans and the established record of their service in the battle, Noble and the other free colored veterans were able to seize the opening provided by the anniversary ceremonies to flaunt this image of black male equality long before it was a viable option in other parts of the region and nation. From the first ceremony of solemn thanksgiving whites had endeavored to minimize the role the veterans had played in securing the victory, but the memory of the free colored veterans service proved to be impossible to eradicate.

The free colored veterans exclusion and subsequent inclusion in the anniversary celebrations illustrates the extent to which the commemoration of the battle’s anniversary was as much a political tool as it was a window onto the ever evolving challenges and changes that the inhabitants of New Orleans and elsewhere in the nation confronted in the antebellum decades.

The Civil War brought new struggles to the New Orleans and the South that would ultimately be reflected in the waning significance of the battle’s annual commemoration. Regardless of the changes that would come to alter how and where the city’s inhabitants acknowledged the anniversary of the victory, the need to preserve a memory of the battle survived. However dimly that flame of remembrance may have flickered in the ensuing decades, today we can as a city be proud of the fact that 200 years after the stunning victory on the plains of Chalmette, the Glorious Eighth still has a place in our civic culture. We can only hope that this flame can be revived again for those who have never known how much the battle meant to those who came before us.

———

Shelene C. Roumillat, Ph.D., is a historian who specializes in the history of the American. South with a focus on African American, urban, and Louisiana history. For more information on events related to the bicentennial of the Battle of New Orleans, visit www.battleofneworleans2015.com.