The Gumbo Family Tree

An excerpt from "Gumbo" by Jonathan Olivier

Published: June 1, 2024

Last Updated: September 1, 2024

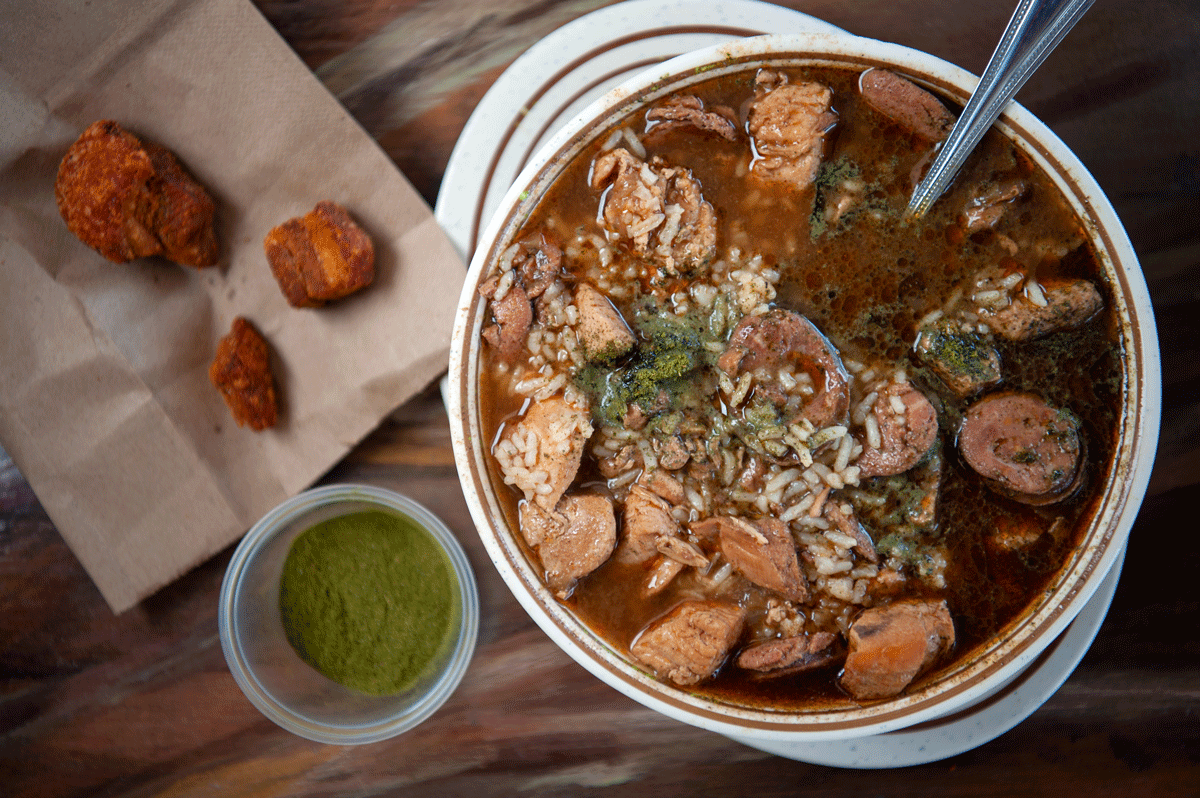

Photo by Rory Doyle

Known around the world as Louisiana’s flavorful soup, gumbo is a complex dish that originated after the convergence of Native Americans, Africans, and Europeans in the region.

Gumbo, by Jonathan Olivier, is part of the Louisiana True series of books from LSU Press, which tell the stories of the state’s iconic places, traditions, foods, and objects. Each book centers on one element of Louisiana’s culture, unpacking the myths, misconceptions, and historical realities behind everything that makes our state unique, from above-ground cemeteries to zydeco. Other titles available in the series include: Mardi Gras Beads, by Doug MacCash; Mardi Gras Indians, by Nikesha Elise Williams; Brown Pelican, by Rien Fertel; and Po’boy, by Burke Bischoff.

LSU Press

In the collective vernacular of Louisiana, cold fronts usher in gumbo weather. Just the slightest hint of a cool snap, which might send temperatures marginally below 70 degrees, functions as a sort of culinary call to arms. The weapons of choice? The biggest stew pot available, a long-handled stirring spoon, and a lot of time to kill. What results after those many hours of stirring, watching, and more stirring is a hearty dish that has, in many ways, come to represent Louisiana cuisine. What actually constitutes a gumbo, though, is much more complicated. While the dish is widely accepted as a sort of thick soup full of an assortment of ingredients, what those ingredients are and how they’re arranged is, for some folks, nothing short of sacrosanct. And Louisianans are just as willing to go to battle over what goes in the gumbo pot.

Often, gumbo opinions have been informed by regional or family traditions that are hardened into deeply held convictions. Put more simply: it comes down to how Mom or Mawmaw cook it. I was schooled in the ways of gumbo by my mom, who grew up in Arnaudville, a small, historically French-speaking community in south Louisiana. She always cooked with chicken on the bone, smoked sausage, and thin strips of smoked pork called tasso. She used roux that she cooked in the microwave, adding it only after the onions, bell peppers, and meat had browned and the broth was simmering. We never had okra, although the blame was on my brothers and me and our finicky tastes. Our rice was always white, steamed to perfection in a dated, olive Hitachi rice cooker that’s a staple in many Cajun and Creole homes. Sometimes we added a pinch of ground sassafras leaves, called filé, right in our bowls, but most times we didn’t. Ritz crackers were a must, used for scooping rice and morsels of meat. If we were lucky, we also got potato salad on the side.

For me, Mom’s gumbo is gumbo.

Yet, her version of the dish and our rituals surrounding it are much different compared to other folks across Louisiana—or even across the street. A friend of mine whom I grew up with starts his gumbo by cooking a roux together with onions, bell peppers, and celery. A New Orleans friend skips the roux entirely, using tomatoes, okra, and oysters. A few vegetarians I know, who can’t imagine going without gumbo, cook with greens and vegan sausage, but they still use a roux for that hearty taste. As New Orleans chef Isaac Toups told me, “Gumbo is different in New Orleans. Gumbo is different in Acadiana. Gumbo is different at my house. Gumbo is different in my restaurants when I do make it . . . Gumbo means something different to everybody else because everybody takes a different interpretation on it.”

Gumbo was born out of a similar spirit of experimentation and regional variation, anchored by a fusion of ethnicities that spanned the globe. It was only possible due to European colonization in North America, enslaved West Africans and Black Creoles, and contact with Native Americans. . . . These groups of people swapped foodways, language, and music to create a new culture thanks to this concentrated diversity in south Louisiana. In French, Cajun, Creole, Houma: A Primer on Francophone Louisiana, historian Carl A. Brasseaux described Louisiana’s cultural landscape as “one of the most complex, if not the most complex, in rural North America.” With so many differing voices from far-flung places in the world, something unique was bound to have been birthed. At the same time, this complex past means that gumbo’s history is as robust as its broth and often as messy as the kitchen after stewing a pot of it.

Since gumbo is a by-product of adaptation and experimentation, it has never really fit neatly into one single recipe, nor has it conformed to claims of authenticity—but that hasn’t stopped people from trying. It’s unclear what makes a gumbo authentic to begin with. Is it the roux, the hearty mixture of fat and flour cooked to almost-burnt perfection? Some might say it’s the okra, an ingredient found in gumbo ever since it was first cooked in New Orleans. Maybe it’s the smoked sausage that has been seared just right in a cast-iron pot. It might be all these things or none of them. There has always been a myriad of ways to make a gumbo that vary by region, cook, and personal preference. When the gumbo was prepared makes a difference, too. In the eighteenth century, some folks made gumbo with cabbage. An 1803 memoir by Frenchman Pierre Clément de Laussat mentioned a gumbo with sea turtles—not exactly a gumbo staple these days.

EXCERPT FROM:

Gumbo by Jonathan Olivier

$21.95; 112 pp.

Louisiana State University Press (February, 2024)