NOLA 300 Music

Ha

The video for Juvenile's hit shows a community that was often ignored, despite the enormous contributions it was destined to make to popular music and culture in the United States

Published: September 3, 2018

Last Updated: March 22, 2023

Aubrey Edwards

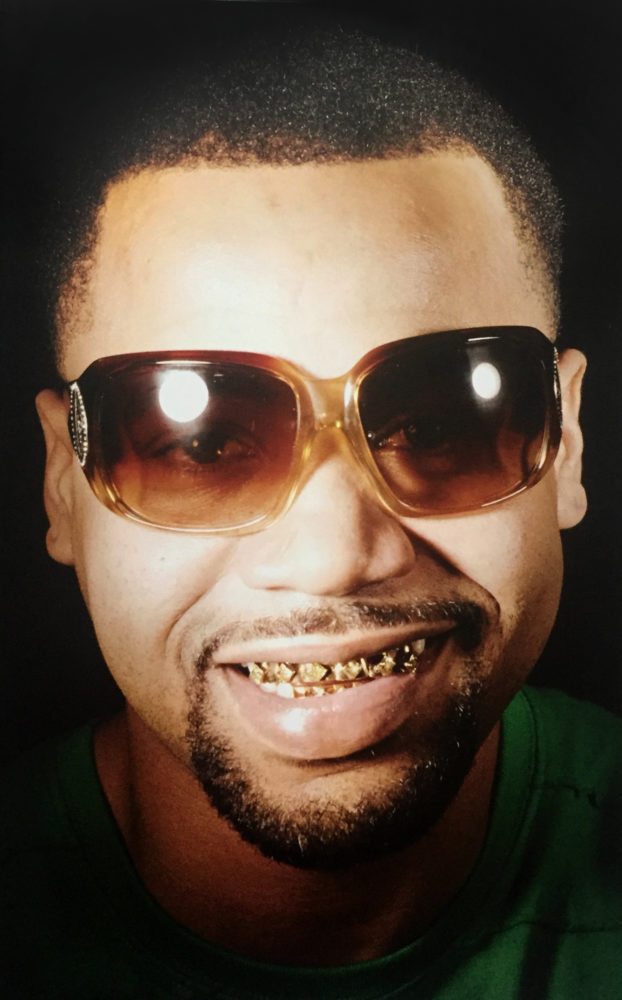

Juvenile's "Ha," from the smash 1998 album 400 Degreez, remains a New Orleans classic.

The accompanying video, which immortalizes the pre-Katrina Magnolia Projects, features numerous images of Juvenile on the street or standing in front of abandoned buildings, interspersed with views of the neighborhood that appear to have been shot from a moving car. The video shows men led away in handcuffs, a group of boys patted down by police, a body loaded into an ambulance and, repeatedly, people chased down alleys by police. There are also images of crowds cheering behind Juvenile, posing on cars, fighting in the streets, and staring into the camera for the series of communal portraits that are interspersed throughout. Along with the verses, the video lends the chorus—with its celebration of a G busy “making nothing out of something”—a specificity and resonance as it attempts to show a community that was often ignored, despite the enormous contributions it was destined to make to popular music and culture in the United States.

The song itself is composed of a series of declarative statements all punctuated by the repeated interjection “ha” (or “huh?”). These statements are presented in the second person, addressed to an unnamed wannabe gangster and describing situations of anxiety, pettiness, and powerlessness that undermine the generic, mythic image of the gangster during a period when gangsta rap still reigned supreme. The “you” the song addresses is identifiable in the first line by his “big ass Benz”; four lines later “you” is being served with a subpoena for lack of child support payments. “You” wants to “run the block” but “you” also “don’t go into the projects when it’s dark / you claim you a thug but got no heart.” Sometimes shout-outs to specific coveted commodities are immediately followed by lines exposing a less glamorous reality, so that “you got a lot of Girbaud jeans” is rhymed with “some of your partners dope fiends.” The first two verses end with triplets that are striking for the succinctness with which they describe an anxiety-producing sense of stasis: “You came to Nolia on New Year’s Eve / You got stuck in that bitch and couldn’t leave/It was hard for you to breathe.”

Some lines sound like taunts and yet the repetition of the “ha,” rooted as it is in a particular speech pattern, has the effect of making “Ha” seem neither accusatory nor celebratory. It is instead revelatory, and the logic of the song as a whole seems predicated on idea of being seen.

Ladee Hubbard received an MFA from the University of Wisconsin, Madison and a PhD from the University of California, Los Angeles. She is a recipient of a Rona Jaffe Writers’ Award and the author of the novel The Talented Ribkins, which won the 2018 Ernest J. Gaines Award. She lives in New Orleans.