Disturbance in Your Mind

The High Priestess of the French Quarter

Piecing together the life of Mary Oneida Toups, a legendary witch of the French Quarter

Published: December 5, 2016

Last Updated: January 30, 2019

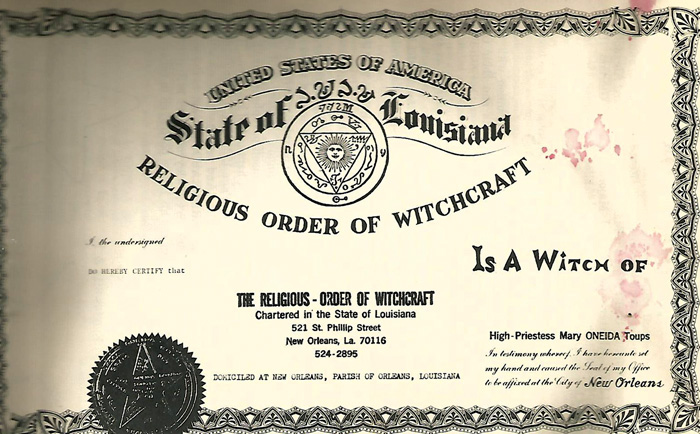

The name-check is all the more surprising because one of the only existing public chronicles of Toups is a chapter in Dr. John’s 1994 memoir “Under A Hoodoo Moon: The Life of the Night Tripper,” which pays more attention to her husband, a lower Ninth Ward native named Albert “Boots” Toups. Boots was a Freemason of high degree who also dabbled, according to the book, in Santeria and the New Orleans spiritual churches, which combined aspects of Catholic saint worship, Christianity, vodou, rootwork and herbal medicine, and which the musician patronized himself. The Religious Order of Witchcraft, the group that Mary Oneida Toups officially chartered with the state of Louisiana in 1972, was only really “alternative” in the sense that it dealt in Western ceremonialist magic, not the African and Caribbean-rooted practices—like vodou and hoodoo folk magic—that are more commonly associated with New Orleans. Still, it was New Orleans that Toups was drawn to in 1968, when she left her birthplace in Meridian, Mississippi, to become, in fairly short order, one of the most well-regarded witches in America.

In the late sixties, interest in the occult and esoteric bloomed on a variety of levels, from superficial aesthetics to genuine spiritual engagement. The Age of Aquarius was the season of the witch; hippies in free-flowing fabrics, flowers, feathers and hair were styled like Merlin and Morgan le Fay and Marie Laveau. Real interest also abounded in nonwestern and other nontraditional beliefs and practices, from the Beat poets’ fascination with Zen Buddhism to Anton LaVey’s founding of the Church of Satan in San Francisco, the year before the Summer of Love. The Beatles followed the Maharishi; Black Sabbath and Led Zeppelin dug into the imagery and mythology of Aleister Crowley and the Golden Dawn. Timothy Leary wrote “The Psychedelic Experience,” his 1964 guide to therapeutic acid trips, using “The Tibetan Book of the Dead” as a central metaphor and model. Out west, in 1968, a woman named Louise Huebner was named the Official Witch of Los Angeles County in a ceremony at the Hollywood Bowl. And Dr. John, of course, lifted the gris-gris imagery of vodou and the spiritual church for his psychedelic hoodoo-man Night Tripper persona, though he had apparently been well conversant with the practice before he adopted the image.

Courtesy of Katina Smith

People were trying all kinds of keys on the doors of perception. It was in that climate that Toups came to New Orleans, chartered the Order and set up shop in the Quarter—at that time still cheap, hip and gritty, the Quarter of “Easy Rider.” Outside of her friendship with Dr. John, though, it seems that Toups intersected little with the city’s counterculture. Born in 1928, she was close to 40 when she got to New Orleans; she had already been married and had a child. Katina Smith, who joined the still-active Religious Order of Witchcraft at the turn of the millennium and served as its high priestess after Katrina, noted that there’s no evidence indicating Toups practiced magic before arriving in New Orleans; yet between 1970 and 1975, she opened two successive witchcraft shops in the French Quarter, organized and chartered the Order—which did, as “American Horror Story” depicted, perform rituals at a then-neglected and overgrown Pop Fountain—and most importantly, published the occult text “Magick High and Low,” which drew praise and gifts from as exalted a figure as Israel Regardie, a writer and magician who had served as Aleister Crowley’s personal secretary. On top of all that, ads in the newspaper indicate that very briefly, in the late ’60s, she and Boots ran a bar at 1141 Decatur Street, now home to Café Angeli.

Mary Oneida came to New Orleans, chartered the Order and set up shop in the Quarter — at that time still cheap, hip and gritty, the Quarter of Easy Rider.

“She was busy,” Smith said. “And if you look at how little time passed between when she started studying and when she wrote the book, she would have had to have had an extremely learned teacher.” Smith thinks it’s possible that Toups studied via correspondence. She also has a couple of ideas as to who might have taught the priestess, if she learned locally. But unfortunately, when Katrina struck, most of the Order’s paper records were in Biloxi and sat in 11 feet of water; one of the only things they salvaged was an oil painting of the high priestess, which today, after no restoration or conservation work, still looks unnervingly fresh. As in the few available photographs of her, the painted Toups looks late-sixties elegant, with arched, groomed eyebrows, long lashes and a fall of brunette hair that brings to mind Bobbie Gentry.

In “Under A Hoodoo Moon,” Dr. John writes that he and Boots ran a voodoo temple out of Toups’ second shop, at 521 St. Philip Street. As far as Smith knows, Boots and Dr. John weren’t part of the Order, and though Toups’ would have sold the regular voodoo powders and floor washes out of the store, the magical work she did was separate. Dr. John hung around the store, he wrote, but the women of the spiritual churches knew he was just a student: “In the coming and goings, a couple of the reverend mothers managed to catch me on the side and pull my coat about the real doings of gris-gris,” he wrote. “They’d tell me, ‘Mac, we got you fronting this thing, but you got to know the real deal; we got to school you about gris-gris.’” The reverend mothers of the spiritual church probably also had little to do with Toups’ work with the Religious Order of Witchcraft, but it’s reasonable to assume—through Boots and Dr. John—everyone was aware of each other.

In 1972, Toups caught the attention of Howard Jacobs, who wrote an odds-and-ends column called “Remoulade” for the Times-Picayune. There had been a murder in Opelousas that the paper reported was somehow related to witchcraft, and Toups had written to its editors in defense of the practice. Jacobs made hay out of the “officially chartered witch” for a few columns, and then appeared to lose interest. Toups only turned up in the news after that briefly, making appearances to promote “Magick High And Low” at literary events, or giving talks on witchcraft to professional organizations like the ladies’ auxiliary of the Society of Petroleum Engineers, who hosted her at a luncheon at the Court of Two Sisters. (Court judgments, which ran in the classified section at the time, also indicate that Boots and Mary Oneida married and divorced each other at least twice.)

Mary Oneida Toups died at the end of 1981. “Under A Hoodoo Moon” claims, ominously, that she was poisoned. According to Smith, it was a mass on her brain that took the priestess’s life—just over a decade after she seems to have found her true path. After her death, Toups’ colleague Russell George, who was High Priest to Smith’s High Priestess after the younger woman joined the Order, took over the shop on St. Philip Street. In 1994, he incorporated his own business there as The Witches Closet.

When she joined the Order in the early 2000s, Smith said, George was the only member left that she was sure had definitely known Toups personally, but he was reticent to answer many questions about the priestess and discouraged other witches from venerating her overmuch. He died in 2014; today, 521 St. Phillip Street is a tourist information center. Smith and a colleague are working on a book about the priestess, and they have had to dig and scramble to verify the details of Toups’ life. So far, they haven’t even been able to find an obituary or a burial site for Mary Oneida Toups or her husband.

“But look what happens at Marie Laveau’s grave,” said Smith, referring to the tomb in St. Louis Cemetery No. 1 that attracts visitors and, on occasion, vandals. “Do you think she’d want that happening to her? I think she wanted to be a mystery. Because she knew she’d be remembered.”

Alison Fensterstock writes about American culture for outlets including NPR, Pitchfork, the Oxford American and others. She has served as the music critic for both Gambit and the Times-Picayune in New Orleans and was the founding program director for the Ponderosa Stomp Foundation.