Magazine

Homegrown Privileges Vanish in Exile

The Whitney Plantation Slavery Museum’s director of research reflects on the central themes in Wynton Marsalis’ 1997 "Blood on the Fields"

Published: June 6, 2016

Last Updated: May 13, 2019

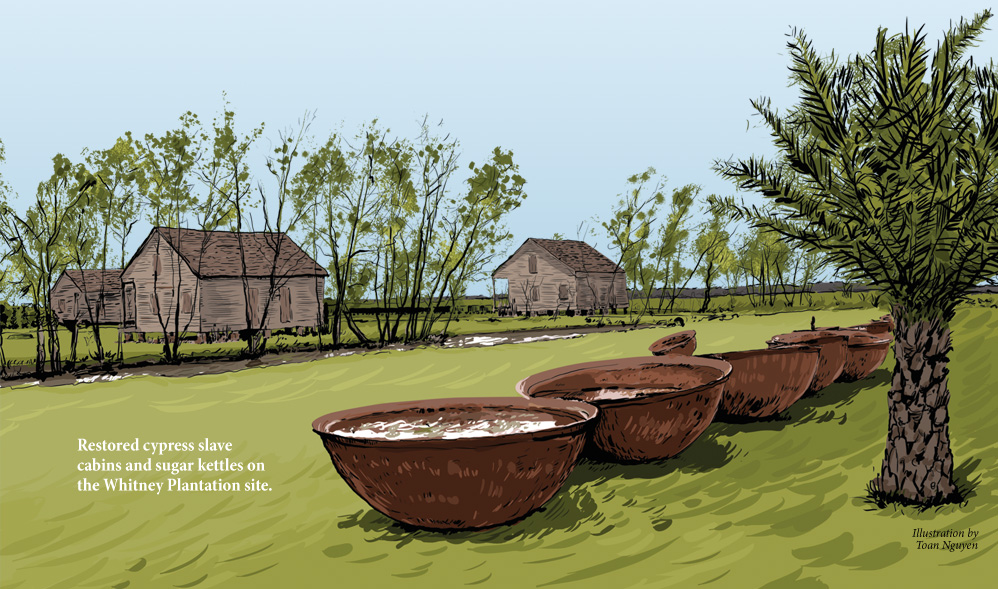

Illustrations of Whitney Plantation by Toan Nguyen

AFRICANS AND THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE

AFRICANS AND THE ATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE

Us sold us to this damned world

All you hear the echoes of dead voices

final screams

– III: You Don’t Hear No Drums

Many African warlords were deeply involved in the slaving business. This allowed the members of the continent’s ruling class to obtain European commodities, which distinguished them from the commoners. Above all, firearms were in high demand for their ability to provide security and as tools to build an empire. Higher quality iron was also desirous for domestic needs. Often used in negotiations, alcoholic beverages ultimately became an essential part of trade. In return, Africans offered cowhides, gum Arabic, bees’ wax and gold, but captives became the most important component. Their labor was much needed in the Americas. After their purchases, slave traders also bought food, wood and water to ensure the nourishment of the human cargo throughout the middle passage.

As a member of African royalty, it is possible Jesse contributed others to this trade before he was captured himself. The Wolof of Senegambia called these warriors Jaami Buur (royal slaves). Garmi designated the members of the aristocracy. Together, the Garmi and the Jaami Buur formed one powerful group called Ceddo, who are still remembered as brutal and merciless warriors as well as a fearless and proud people, much like the knights of Europe.

Many centuries before the beginning of the Atlantic slave trade, captives were exported across the Sahara Desert, but this early slave market could not meet the huge demand of the Americas. Since captives were typically obtained through wars, a reliable solution to the problem was to generate permanent warfare between nations. The European companies invested in these conflicts and backed those who most aided their interests. Locally, political successions were turned into devastating civil wars. The foreign companies supported the contenders whom they could later use as dedicated allies for the slave trade. French philosopher and political activist Marquis de Condorcet (1743-94) was quite aware of these intrigues, as he describes in the pamphlet Reflections on Negro Slavery (1781):

“It is the infamous commerce of the brigands of Europe that generates between the Africans almost continuous warfare which only motive is to make prisoners destined to the trade. Often the Europeans themselves foment those wars with their money or their intrigues, which make them guilty not only of the crime of enslaving people but also of all the murders committed in Africa in preparation of this crime.”

This voice of the past reminds us that African warlords counted on the support of external forces that the African peoples did not control. This is also quite reminiscent of Postcolonial Africa when people like Kwame Nkrumah of Ghana, the Congo’s Patrice Lumumba or Burkina’s Thomas Sankara—leaders who dared to say no to exploitation and alienation—were either exiled or killed by coups d’état orchestrated by foreign economic interests.

Abdul Rahman Barry—the son of Ibrahima Sori who was the Almami (leader) of the Fulbe Kingdom of Fuuta Jallon in West Africa—is perhaps the most famous among those Africans enslaved along the Mississippi River and mirrors Jesse’s plight. His story is described in Terry Alford’s Prince Among Slaves. Captured in 1788 during a war against the neighboring Mandingo kingdom of Kaabu and sold into slavery, he was taken to the Caribbean island of Dominica and then to New Orleans. There he was sold to Thomas Foster, a planter established in Natchez, Mississippi. Barry spent 40 years in bondage before he was eventually freed and able to return to Africa on one of the African Colonization Society’s boats. Before he was enslaved, Barry was a member of the African elite and was involved in the many wars that supported the Atlantic slave trade. He became the victim of the same business on which the power of the kingdom of Fuuta Jallon was built. His claims of royalty only brought him the laughter of his master who mockingly referred to him as Prince. Once again, Jesse’s fate in Blood on the Fields is similar. He is also a prince who finds himself in the hold of a vessel bound to America stripped of his station’s respect and dignity.

THE MIDDLE PASSAGE

Death bound river of blood flow

Reeking foul, stench down below

All you hear, the shrieking howls of so

much misery

– III: You Don’t Hear No Drums

On the same boat with Jesse is Leona—a “low born woman,” as he calls her—which is full of bitter irony. Here is a prince forced to unite with commoners through this process of enslavement. It does not matter that they might be from his village or the same peaceful and defenseless farmers kidnapped by mercenaries who are armed by European companies and linked to local elites like Jesse.

On the boat, Leona is inconsolable and Jesse shouts, “Stop your whining common girl.” A Ceddo prince does not cry even when facing death, especially not in front of people of lower extraction like Leona. “I’m a prince, my heart is stone,” he adds as a boast. Men and women were separated in that ship’s hold, and physical contact between them isn’t possible unless they meet on the deck of the ship when they are fed or forced to dance to keep themselves in shape. Though Leona is already in love with him, Prince Jesse refuses to pay her any mind: “Common girl don’t ask me for no love.”

Nevertheless, he soon learns the lesson behind this Fulbe proverb: “Ladde andaa bii mojjo” or “Homegrown privileges vanish in exile.” Though not yet a slave, the overseers often ridicule him with loud laughter whenever he shares his princely claim on the floating jail that would take him to America.

Could not count the slaves I owned

All you hear, the mocking cry of past

accomplishments

– III: You Don’t Hear No Drums

ENSLAVEMENT AND RESISTANCE

Checking their teeth and hairlines

Pinching a buck whose skin shines

Looking for brown concubines

– IV: Soul for Sale

Once the African captives arrived in the Americas, they underwent a painful period of adjustment known as “seasoning,” which completed the process of enslavement. This period could last up to three years allowing them to acclimate to their new environs and the shock of the new world. Africans not only had to survive their brutal treatment and disease, but also the heartache of missing home.

Jesse’s enslavement begins with the supreme humiliation of being inspected like an animal and sold to the highest bidder. Besides this horrific experience, he likely experiences true terror for the first time since he took his first step into manhood after his initiation in Africa. At this stage, his experience might mirror that of Olaudah Equiano, a freed slave and noted abolitionist in England who was captured somewhere near the Bight of Benin. He noted the following in his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano:

Jesse’s enslavement begins with the supreme humiliation of being inspected like an animal and sold to the highest bidder. Besides this horrific experience, he likely experiences true terror for the first time since he took his first step into manhood after his initiation in Africa. At this stage, his experience might mirror that of Olaudah Equiano, a freed slave and noted abolitionist in England who was captured somewhere near the Bight of Benin. He noted the following in his 1789 autobiography, The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano:

“We were not many days in the merchant’s custody before we were sold after their usual manner. The noise and clamor with which this is attended, and the eagerness visible in the countenances of the buyers, serve not a little to increase the apprehensions of the terrified Africans. We thought by this we should be eaten by these ugly men, as they appeared to us. The white people got some old slaves from the land to pacify us. They told us we were not to be eaten, but to work, and were soon to go on land, where we should see many of our country people.”

The foreign slave trade into the Orleans Territory was forbidden after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, a law eventually extended to the rest of the United States in Jan. 1808. Though thousands were smuggled from Africa and the Caribbean through a newly created and illegal slave trade, the vast majority of slaves were traded domestically between the American Upper and Lower South regions. This internal slave trade became a very lucrative business between the 1820s and the 1860s. Its proponents spent their time buying enslaved people in the Upper South during the summer when Louisiana was exposed to the heat that nurtured a vector of maladies such as malaria, yellow fever and cholera. Some of those purchased in the upper region were transported on boats to New Orleans, but the vast majority were walked to the Lower South over a period of seven to eight weeks.

Jesse finds himself chained to one of the southbound coffles.

Necks wringed with iron in agony

We drag on feet cut bare by ground

For endless miles did not sit down

– V: Plantation Coffle March

Owners implemented a “system of divide and conquer” in which some enslaved people were promoted to positions of privilege. Perhaps best known are the domestics who served the masters in and around the Big House and were given better food and clothes than their counterparts. On the other side were the field hands who worked under overseers, called “commandeurs” on Louisiana plantations. The gruesome fact is that these foremen were also enslaved people, but they were given the power to handle punishments.

In Blood on the Fields, Jesse and Leona become hands on a cotton plantation and work from daybreak to dusk to a pace imposed by the whip. As they toil, they sing spirit-lifting songs.

Drive! Driver, hold that whip

Drive! Driver, hold that whip

[…]

Blood on the fields

King cotton grow

Brown soil yields

White up above

Red down below

Take me home

Far, far away

– VI: Work Song (Blood On The Fields)

Though religion was used to justify the enslavement of Africans, it was also a vital tool to control the minds of the enslaved. “They, however, interpret the word of God quite differently,” it’s sung in “VIII: Oh We Have A Friend In Jesus.”

Born into slavery in Louisiana, Elizabeth Ross Hite’s testimony is a perfect illustration of the enslaved people’s agency as they created the Black Church on the premises of their masters:

“My master brought a colored man from France to teach us how to pray. But we had our own church in the brickyard way out in the field. Old man Mingo preached and there was Bible lessons. He gave sacraments in a cup.”

But this God is of no interest to Jesse, who is never able to get adjusted to his new life. In IX: Juba and a O’Brown Squaw, the chorus says, “Jesse thinks not of God, not of heaven, not of jus-tice, only his own freedom is on his mind. He goes to see Juba. A man so wise, the uninformed think he is a fool.”

Marsalis’ main source of inspiration is Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s Africans in Colonial Louisiana (1992), a seminal book that has redefined our understanding of Southern slavery complex.

The name Juba originates from Africa. Among the Fulbe of West Africa, Juba is a name both for humans, for a kind of bird and for a famous dance that probably gave birth to the juba patting of the American South. Juba warns Jesse about the many trials he faces before he can reach freedom, the most terrifying being the blood hounds: “Dogs got long and pointy teeth and would love some brown behind.” Juba also advises Jesse to seek the alliance of the Indians “Be sad but sing a happy song to call the Indians out,” he says. “Any man be an Indian no matter how he’s born.”

Both Africans and Indians were enslaved on the plantations of Louisiana, and marriages were widespread between them. “Grif” was the racial designation used for their children. The Native Americans were precious allies for the enslaved Africans who ran away from their masters. But, as it says in “X: Follow The Drinking Gourd,” “Jesse don’t care about no Indians, no land, no soul, no singing, and no Leona. It was time for him to go ahead and run.”

Slavery was based on inflicting violence to the bodies of the enslaved. This violence was institutionalized through the so-called “black codes” with total obedience as its expected result. Marronage (running away) is its rejection and a central piece in the oratorio, but the price of failure was great. According to the first black code of Louisiana, those recaptured were to have their ears cut off, be branded with the fleur-de-lis, have their hamstrings cut or be sentenced to death if they persisted in their escape efforts.

Leona spends much of her time praying for the return of the man she loves, but she soon regrets this once her wish is fulfilled. Jesse is not successful in his escape and goes on to “feel the bitter lash of failure.” He is neither branded nor hamstrung, his ears are not cropped, but he is “dog-bit and chain-burned” and has to suffer 40 lashes on his bare back. Thereafter Jesse eventually drops his complex of superiority and accepts Leona’s love. Though Jesse’s flesh is now tamed, his “soul” is not. He continues to pursue resistance by playing the blues:

Sun is gon’ shine

When you see me dancing down the street

Singing

Know that I sing a song with soul to be

free

Which I soon will be.

– XVI: The Sun Is Gonna Shine

Blood on the Fields continues to be relevant today as there is a renewed interest in the history and memory of slavery. Apparently, Wynton Marsalis’ main source of inspiration is Gwendolyn Midlo Hall’s Africans in Colonial Louisiana (1992), a seminal book that has redefined our understanding of Southern slavery complex. According to noted jazz journalist Ted Panken, Marsalis wanted Blood on the Fields to be “tragic the whole way through, with no redemption,” but philosopher Albert Murray ushered him in changing his perspective. He told him, “You’ve got to understand that if you make it all tragic, you’ll be coming from an expression that’s not really Afro-American.”

As Panken explains, somehow the philosopher helped the musician better understand “the transcendent value of the blues and of swinging.” In other words, he caused him to comprehend the power of culture as a liberating force. Though the masters may have had control over the bodies of the enslaved Africans and their descendants, they never owned their souls. Jesse plays the blues to stay alive while connecting to his motherland until he escapes north to freedom with Leona. Today, The United States is similarly burdened. Though the country might seek to move past its checkered history, it can only seek to transcend because it is impossible to forget.

—–

Dr. Ibrahima Seck is a member of the History Department of Cheikh Anta Diop University of Dakar, Senegal. He currently holds the position of the director of research of the Whitney Plantation Museum of Slavery, located in St. John the Baptist Parish. He is the author of Bouki fait Gombo: A History of the Slave Community of Habitation Haydel (Whitney Plantation) Louisiana, 1750-1860, published by the University of New Orleans Press in 2014.

This article was made possible by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a program to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Prizes in 2016. Announced by the Pulitzer Prize Board, the Campfires Initiative aims to ignite broad engagement with the journalistic, literary, and artistic values the Prizes represent. The board partnered with the Federation of State Humanities Councils on the initiative and awarded more than $1.5 million to forty-six state humanities councils. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities received $34,000 to support articles in Louisiana Cultural Vistas and public programs around the state about Pulitzer winners with ties to Louisiana. On Saturday, August 6, 2016, the “Let Them Talk” symposium at the 2016 Satchmo Summerfest in New Orleans hosts “Satchmo to Marsalis: How Louis Armstrong helped shape the musician Wynton Marsalis,” a panel discussion moderated by James Karst of The Times-Picayune. Visit fqfi.org/satchmo for more information.

This article was made possible by the 2016 Pulitzer Prize Centennial Campfires Initiative, a program to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the Prizes in 2016. Announced by the Pulitzer Prize Board, the Campfires Initiative aims to ignite broad engagement with the journalistic, literary, and artistic values the Prizes represent. The board partnered with the Federation of State Humanities Councils on the initiative and awarded more than $1.5 million to forty-six state humanities councils. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities received $34,000 to support articles in Louisiana Cultural Vistas and public programs around the state about Pulitzer winners with ties to Louisiana. On Saturday, August 6, 2016, the “Let Them Talk” symposium at the 2016 Satchmo Summerfest in New Orleans hosts “Satchmo to Marsalis: How Louis Armstrong helped shape the musician Wynton Marsalis,” a panel discussion moderated by James Karst of The Times-Picayune. Visit fqfi.org/satchmo for more information.