Coastal

How to Tarp the Past

Hurricane Ida forces public historians to make difficult decisions

Published: February 28, 2022

Last Updated: May 31, 2022

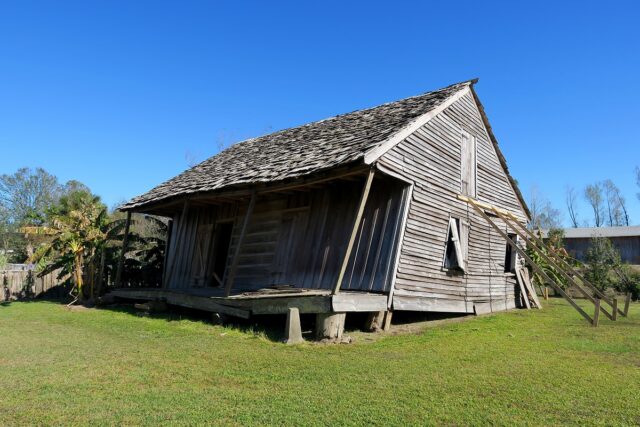

Photo by Morgan Randall

A mule barn original to Woodland Plantation, now on property neighboring the 1811/Kid Ory Historic House, lies demolished in a field in January 2022.

For managers and directors at historical sites, hurricanes pose an additional question: What do we fight to preserve and what do we leave to risk winds and rain?

John McCusker is the founder and managing director of 1811 Kid Ory Historic House in LaPlace, a town hard hit by Hurricane Ida in late summer 2021. The museum, which opened in February 2021, tells the stories of the 1811 German Coast uprising, a rebellion of enslaved people that began on the property, and the life of Edward “Kid” Ory, a pioneering jazz musician who was born in the workers’ quarters in 1886, when the site was part of Woodland Plantation.

McCusker and Operations and Programming Manager Charlotte Jones rode out the storm at the museum. Although McCusker was used to sheltering in place, having chased down and documented hurricanes as a former photojournalist for the Times-Picayune and the New Orleans Advocate, Ida was different. “Not during Katrina—not during any of it—was I as terrified as I was that night,” he said.

At one point during the storm, wind blew out the gabled windows and filled the attic with rain. “All that [rain] mixed with two hundred years of detritus and came down through the ceiling,” McCusker said.

As water seeped through the wood ceilings and walls, McCusker and Jones protected what they could with tarps and moved the rest. When asked what artifacts were at the top of his list, McCusker didn’t hesitate.

“We’ve got the largest Kid Ory holding in the world,” he said. The collection includes a sizable paper archive of all of Ory’s music dating back to when he played with Louis Armstrong in the 1920s; handwritten manuscripts by Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton; and photographs of which there are no known copies. Fortunately, McCusker and Jones managed to protect everything from water damage.

While they raced to preserve history inside the house, Ida made quick work of destroying buildings outside. Two structures on the neighboring property had collapsed: a shed and a mule barn that were once part of Woodland Plantation. The wind had been so loud during the storm that McCusker and Jones hadn’t heard the buildings fall.

Though it was a tough turn of events for a museum that had only been open seven months, 1811 Kid Ory Historic House began welcoming visitors again in early October. By January 2022, signs of Ida were relegated to the outdoors, where the shed and mule barn still lay in a heap in the field behind the house. In the distance, blue tarps fluttered on the roofs of the quarters where Ory was born.

Repairs to the museum, however, were complete. The beadboard ceilings, formerly stained brown by stormwater, had a new coat of white paint. A French interpreter was working on translating the exhibits, and McCusker was excitedly preparing to install a new display about the house Ory was likely born in. Thoughts of Ida seemed mostly behind him.

A slave cabin damaged by Hurricane Ida at Whitney Plantation is braced on three sides. Photo by Morgan Randall

It was a different story for Whitney Plantation, a museum that focuses exclusively on telling the stories of enslaved people, located about ten miles up the Mississippi River from McCusker’s museum. Unlike 1811 Kid Ory Historic House, which reopened just a month after Ida, it took Whitney Plantation three months to welcome visitors again. Roughly fifteen buildings on the property were damaged or destroyed by the storm.

The most noticeable change was in the slave quarters. At the beginning of 2021, Whitney Plantation had seven cabins, some of which had been built to house enslaved people, and some of which may have been constructed after abolition. “By the end of 2022, we’ll probably only have two,” Executive Director Ashley Rogers said. “We’re not done losing buildings yet. This is an ongoing process.”

As of January 2022, the two cabins in the best condition were still missing some siding. One needed to have its front porch rebuilt. A third cabin was in an active state of collapse, with braces on three sides. A fourth cabin was missing its entire top half, the loft having blown off in Ida’s winds. What was left was protected by a blue tarp.

The hurricane flattened the final three cabins. All that remained of them were a few dirt patches in an open field. Though the structures were original to Myrtle Grove Plantation in Terrebonne Parish, their loss is still significant.

“They’re not from the Whitney originally, but they are part of the historical fabric of Black life in Louisiana,” Rogers said. “We’re one of the few historical organizations in the state that really preserve the history and the built environment of enslaved and emancipated people. I don’t want to lose any of it. It all has something to say about that history in this state, and now that’s gone.”

Fortunately, projects completed a few years before Ida ensured that the hurricane couldn’t erase those structures entirely. In 2020, Whitney Plantation used a historic preservation grant from the National Park Service to survey and document all the buildings on the site. The National Park Service also used 3D imaging to document one of the cabins Ida destroyed a year later.

Rogers has turned her attention toward restoring the remaining structures, which include the slave cabins, plantation store, big house, and chapel, among others. But recovery could take years. By Rogers’s estimate, insurance would only cover about $200,000 of up to $1 million in damages, leaving her with some uncomfortable choices.

“As a public historian, this is a very weird position to be in, of having to make these triage decisions,” she said. “What can be saved? What are the priorities in terms of what we need to be focusing our resources on? What will be too much for us?”

There is also the looming threat of stronger storms with increased frequency. At one point in our conversation, Rogers wondered whether the plantation’s long-term preservation was feasible.

However, Rogers and her team will keep fighting for the planation. To prepare for future hurricanes, staff will develop a response plan based on what they learned in Ida’s aftermath. There are also plans to repurpose the space where the slave cabins used to stand. Some ideas include adding exhibits demonstrating how indigo was processed or how sugarcane was boiled at the plantation.

While leading me on a tour of the grounds, Rogers would occasionally stop to scrutinize damage or repairs underway: an open door on one of the surviving slave cabins, construction materials next to the plantation store, a fallen fence along the property line. Still, signs of Ida’s destruction didn’t detract from my experience as a first-time visitor. Some of the most moving points along the walking tour—the plantation’s 1811 German Coast uprising memorial, a list of more than 100,000 known names of people enslaved in Louisiana, and a wall commemorating those enslaved specifically at Whitney Plantation—had been untouched by Ida. After Rogers and I parted ways, I returned to the 1811 uprising memorial, which had been on my mind since leaving the 1811 Kid Ory Historic House earlier that day.

“There is this incredible power of being in this place,” Rogers had said during an earlier conversation. Standing in the middle of the memorial, the vast fields stretching away, the world silent except for an unseen wind chime tinkling nearby, it was easy to feel that power. Thanks to Whitney Plantation staff, the site remains available for others to discover it for themselves.

Yet not all historic sites affected by Ida have a Rogers or a McCusker to protect them. Thirty-five miles east of Whitney Plantation, nothing remains of the Karnofsky Tailor Shop and Residence, a two-story brick building that stood on South Rampart Street in New Orleans for over a hundred years. It was an important fixture in Louis Armstrong’s childhood. Until he was twelve, Armstrong worked for the Karnofsky family by collecting junk like bottles and rags and delivering coal to sex workers in nearby Storyville. With a two-dollar advance from Morris Karnofsky, Armstrong was able to buy his first cornet. Morris praised the budding musician as he learned how to play the instrument.

The Karnofsky Shop’s role in Armstrong’s life made it one of four buildings on the 400 block of South Rampart Street central to early jazz history, along with the Little Gem Saloon, Eagle Saloon, and Iroquois Theater. Yet the shop sat empty for years as it was sold from one owner to the next, its future often murky. At one point, it belonged to the Arlene & Joseph Meraux Foundation, which spent $1.5 million to stabilize it and the Iroquois Theater. In 2016, the foundation traded the shop with developer Joseph Georgusis for property in St. Bernard Parish. At the time of its collapse, public records listed Rampart Partners LLC as the building’s owner, with a mailing address for a Cleveland-based real estate developer known as GBX Group. The same mailing address was listed for the owners of the Iroquois Theater.

As Ida approached southeastern Louisiana, the Karnofsky Shop, Iroquois Theater, and Eagle Saloon all sat in a state of decay, even though each structure was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Little Gem Saloon had been restored, but even that was not enough to protect it from Ida: when an exterior wall fell during the storm, it took with it a colorful mural of jazz pioneer Buddy Bolden and his band by Brandan “B-mike” Odums.

However, to say that the Karnofsky Shop had no one looking after it at the time of its collapse would be disingenuous.

“When it went down, those boards on the front door were mine,” said McCusker, who, before becoming managing director of the 1811 Kid Ory Historic House, pressured the Meraux Foundation to restore the Karnofsky building. “I had boarded the building up.”

McCusker called the property manager a couple of years prior, concerned that trespassers were damaging the building. The manager allowed him to seal the shop, provided McCusker bought his own wood and deck screws. In any other storm, those boards might have been enough protection.

Ida was only one of eight named storms that rocked southern Louisiana in 2020 and 2021. If the frequency of severe weather events continues to follow this trend, it stands to reason that the loss of historic structures and artifacts will increase, too. Historians, preservationists, and concerned citizens simply do not have the resources to protect or rebuild it all. As the Karonfsky Shop demonstrated, you can try to board up the windows, but it still might not make any difference.

Morgan Randall is a writer exploring stories about the relationship between us and our shifting environment.