Summer 2018

Huey Long vs. The Media

In his clashes with the press, the Kingfish used legislation, slander, and even physical force to control the message

Published: May 31, 2018

Last Updated: November 6, 2018

Long seemingly felt no compunction about making dubious claims against perceived political enemies, even wounded war heroes.

President Trump’s prolific and often provocative use of his Twitter account, including his willingness to name and troll reporters who fail to flatter or agree with him, has left many Americans feeling as if they are in uncharted historical territory. But even this naked enmity between the press and powerful politicians, and the insistence on using a personal media platform to trumpet a self-aggrandizing narrative with a tenuous relationship to facts, have historical precedent. One need only look back to the rise and reign of Louisiana Governor and US Senator Huey P. Long—the self-described “Kingfish”—to find a historical example rife with contemporary resonance and replete with an astounding number of episodes that suggest just how far a demagogue might be willing to go in controlling press coverage, including circumventing and punishing media outlets that fail to flatter him or support his political program. In short, looking back at Louisiana in the 1930s can help contextualize the present and remind readers of the critically important role a free press played in a time and place where the state’s democratic institutions were being threatened.

Even before he first ran for a seat on the state’s Railroad Commission in 1918, Long was an inveterate attention seeker who wrote letters to legislators or newspapers not simply offering advice but often exhorting elected officials to act as he directed. As he began his first campaign for governor in 1923, Long made a shift from writing letters to creating circulars whose message he alone controlled. These broadsides were intended, through wide distribution, to promote his political brand, defame anyone who opposed him, and, very often, confront the press about what he deemed its unfair treatment of him. In one circular based on a speech he had given, Long complained: “One day you pick up the papers and see where I killed four priests . . . Another day I murdered twelve nuns, and the next day I poisoned four hundred babies.” Of course those who heard or later read these remarks knew they were not technically true. But the people who supported Long’s populist political program were generally willing to overlook his habitual overstatement—especially when it made them laugh. Yet this comical hyperbole also served the purpose of belittling and undermining any legitimately negative press coverage he received.

Most of Long’s biographers have devoted close attention to the way in which he sought to control the press by seeking their support, and, if he did not receive it, attacking and undermining their message and mission. One of his most well-known disputes was with Charles Manship, publisher of the Baton Rouge State-Times. Long sought Manship’s support but, when it was not forthcoming, resorted to threats. Specifically, the governor threatened to publicize the fact that Manship’s brother Douglas was confined to a mental hospital. Rather than give in, Manship exposed the governor’s intimidation and printed the news himself. In an editorial, Manship also took a swipe at Long’s draft-dodging in World War I, reminding readers that while Douglas Manship was serving in Europe, where he suffered incapacitating shell shock, Long was making his first run for political office. In response, Long went on the offensive against both brothers, descending to appalling levels of tastelessness in the process. Long told a New Orleans audience that Douglas Manship’s mental illness was not the result of a war injury but, rather, evidence of senility caused by syphilis. Long seemingly felt no compunction about making dubious claims against perceived political enemies, even wounded war heroes.

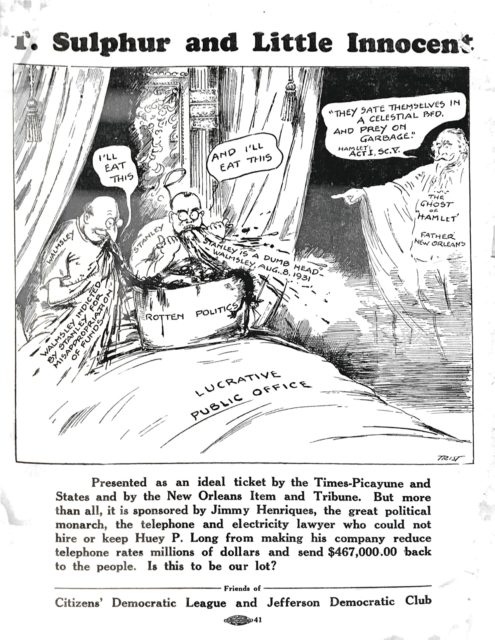

A broadside published during Long’s clash with New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley. Courtesy of Hill Memorial Library at LSU

Long’s attack on the Manships had direct political consequences for the new governor. When the Louisiana House of Representatives initiated impeachment charges again Long in 1929, the episode with Manship laid the foundation for one of the articles lodged against him. Long went on the offensive, penning circulars that warned the public they could not trust what they read about him in “the lying newspapers.” In the end, Long managed to short-circuit the attempt to remove him from office by making promises and payoffs to enough legislators to block a successful impeachment vote in the State Senate. After that brush with political disaster, Long consolidated his political power by doing what he described as “dynamiting” the opposition out of his way. In this spirit, he also continued his campaign against the press along two fronts. In 1930 he started his own newspaper, named the Louisiana Progress, which allowed him to control the content of at least one press outlet entirely. Like the Kingfish himself, the paper had an erratic and unpredictable schedule, but, despite its one-sided editorial stance, its subscribers numbered in the thousands, many of whom were state employees advised to take out at least one subscription to show their support for their “patron.” Distribution was likewise made possible by the efforts of state employees, including police who acted as glorified newsboys in state vehicles as they distributed Long’s newspaper to every corner of Louisiana.

He ordered his bodyguards to physically attack press photographers who were trying to capture an image of the Senator with a shiner.

Long opened a second front against the press in the legislature. In 1930 he proposed a bill that would levy a “fifteen percent tax on all gross revenues” that newspapers “received from advertising sales.” Because this tax would have targeted newspapers specifically, it was clearly intended to exact an undue burden on this particular kind of enterprise. Punitive taxation aimed at newspapers has a long history and, in fact, provided part of the rationale for why American colonists rose up against the British. One of the taxes that colonists rejected most vehemently was The Stamp Act, which put colonial newspaper publishers at the mercy of British Commissioners of Stamps and was, in essence, an attempt to restrict the circulation of radical ideas to restive colonists by making newspapers more expensive. When the Congress proposed the First Amendment to the US Constitution, punitive English press levies were fresh in their minds.

At least as alarming as the punitive newspaper tax was Long’s proposal to allow the state to seek an injunction to stop the publication of any newspaper deemed “obscene, lewd, or lascivious,” or “malicious, scandalous, or defamatory.” Since the state would have determined which newspapers met these descriptions, and because Long had significant control over state operations by this time, the bill would have given him the ability to decide which newspapers were targeted under the law. Both of these proposals were blocked in committee in 1930 and never received a vote. Long would try again four years later.

Even though at this point he had his own press outlet whose only mission was to promote his initiatives and skewer his political opponents, Long was not satisfied. His desires for power, attention, and acclaim had only expanded by the time he was sworn into the US Senate in 1932. As a senator, virtually all of Long’s efforts were focused not on advocating for his Louisiana constituents but rather on promoting himself, his ideas, and his own apparently limitless political ambitions. To that end, he repurposed his newspaper, renaming it American Progress. It was similar in tone and intent to the state-based version, but the paper now featured Long’s policy prescriptions for the entire nation, including proposals for solving the ills of the Depression, righting the evils wrought by unfettered capitalism, and making clear that he was the only person with the vision and ability to solve the nation’s problems.

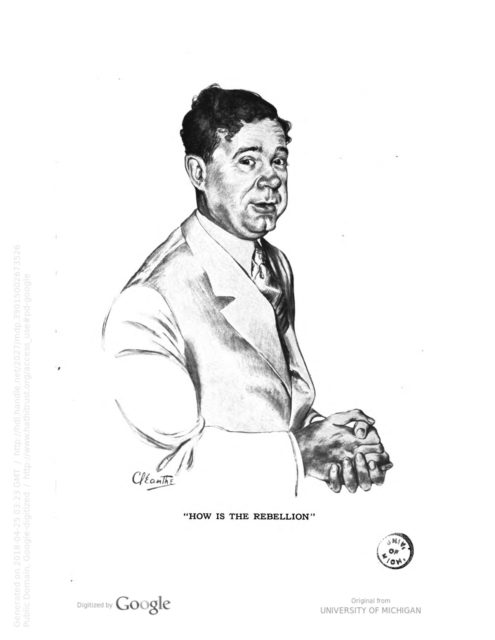

Long’s utopian novel, My First Days in the White House, was published posthumously in 1936. Long imagined an unnamed governor who faced an angry mob due to his resistance to the Share our Wealth Program. “How goes the rebellion?” the Kingfish asked the governor. “All right,” replied the governor, “but you have all the rebels.” Public domain, Google digitized.

By 1933, after serving only one year in the Senate, Long’s national profile had grown tremendously. Many Americans responded to Long’s proposed political solutions by penning enthusiastic letters of support. He received far more mail than any of his Senate colleagues. He also managed to attract near-continuous media attention through lengthy, colorful filibusters and on-the-air radio rants, which were broadcast to sets nationwide.

Yet his rising visibility did not always generate flattering coverage. In fact, in the summer of 1933 Long briefly became the subject of nationwide ridicule. The embarrassing episode that led to this reporting took place at Sands Point Bath and Country Club, located in a prosperous area of Long Island. Spectacularly intoxicated, Long had evidently made a drunken faux pas in the men’s room—likely urinating on the leg of another man—which garnered him a stiff punch in the face and a resulting black eye. In the aftermath, at least one newspaper dubbed him Huey “Pee” Long. When he arrived back in New Orleans several days later, he ordered his bodyguards to physically attack press photographers who were trying to capture an image of the Senator with a shiner. They obeyed, assaulting one photographer with a blackjack and smashing his camera to bits.

This incident established for the first time that Long was even willing to order violence against the press to discourage negative coverage. A similar incident occurred a year later when the Kingfish roared into New Orleans and made a stop at his elegant uptown mansion. This time Long ordered state guardsmen who were protecting his house to take a photographer’s camera away. The soldiers complied, damaging the camera and nearly tearing the man’s shirt off in the process.

After being elected US Senator, Long waited nearly two years to be sworn in. He left the governorship for Washington only after he had engineered the subsequent Louisiana gubernatorial election to ensure that O. K. Allen would become his handpicked successor. Just in case Allen should deviate from any of Long’s directives, the Senator returned home frequently to supervise Allen’s actions, interfere in local elections, and pull political strings to make anyone who opposed him look bad.

New Orleans Mayor T. Semmes Walmsley was one of those politicians Long kept in his sights. Walmsley had drawn Long’s ire by refusing to submit to his political demands. Over the years Long had found numerous ways to punish Walmsley and the city itself by assigning control of many city services to state committees that had no New Orleans members but plenty of Long loyalists. In 1934 Long decided to use the power of publicity to question Walmsley’s management and smear his upright reputation.

Long had the legislature authorize an attention-grabbing investigation designed to critique moral conditions in New Orleans, suggesting that the city was a hotbed of sin and that Mayor Walmsley was ignoring and possibly even facilitating the widespread presence of gambling and prostitution. Long then had himself named chief counsel for the hearings. For several days in early September, Long had witnesses—or what the local newspapers, ever suspicious of Long, referred to as “purported witnesses”—called before his committee. Their testimony was broadcast over the local radio station WDSU, but the public and the press were otherwise barred from the hearings. The hearings resulted in no charges against local officials; the whole episode amounted to an attempt to carefully control and deploy media to make a political opponent look bad in the weeks leading up to an election.

In Louisiana, antics like this were made possible by the fact that most of the state’s voters remained supportive of Long, found him amusing, and, crucially, were won over by the phenomenal leaps forward in the development of state infrastructure and substantive improvements in the public weal. Yet Long’s complete disregard for the central tenets of democratic practice now generated headlines and editorial critiques from other locales whose presses and editorial stances he could not control. National reporters and news magazines were not dependent on Long’s largesse, and the voices of critique grew sharper in his final year of life.

The acclaimed American novelist Sinclair Lewis was so alarmed by what he saw Long doing in Louisiana that he was inspired to pen the novel It Can’t Happen Here in the summer of 1934. The dystopian tale has as its protagonist a weak-willed newspaper publisher named Doremus Jessup, facing down an unlikely demagogue named Buzz Windrip. By the time Jessup and the novel’s other characters understand the political threat posed by Windrip, events have overtaken them. Democratic institutions exist in name only, and the only press outlets allowed to publish are those that unfailingly flatter Windrip. Now president, Windrip empowers a resentful army of “forgotten men” to engage in shocking acts of violence against anyone who dares to dissent.

Lewis’ fictional predictions were dire and likely darker than most Americans were willing to accept as being comparable to Long’s capacities. Yet, even while Lewis wrote, Long was extra-legally engineering the adoption of Louisiana legislation designed to punish his opponents in the press. This time around, the law levied only a 2 percent tax on all the proceeds paid to newspapers by their advertisers. The bill passed. Long also saw to the creation of a State Printing Board that determined which newspapers would serve as the state’s official journal. This was a lucrative contract, especially for small newspapers that depended on advertising dollars, even if those advertisements were paid for by the state itself. More importantly, this board gave Long the ability to reward or punish press outlets based on their coverage of him.

Legislation like this was made possibly because Long continued his extra-legal practice of requesting Governor Allen call Special Sessions of the legislature for Long to supervise, during which legislators supinely passed dozens of Long’s mostly punitive proposals into law. United States Senator Long was overseeing just such a session in the Louisiana State Capitol on Sunday, September 8, 1935, when he was shot on the main floor of the towering capitol building, the construction of which had recently been completed and for which he took credit. Long ran screaming and cursing from the building, proclaiming that he’d been shot. His heavily armed bodyguards pumped more than sixty bullets into the body of Long’s alleged assassin, Dr. Carl Austin Weiss.

Huey Long surrounded by bodyguards, ca. 1933. Courtesy of Seymour Weiss Papers, Hill Memorial Library, LSU

After the Kingfish expired on the morning of September 10, his body lay in the state in the same building in which he’d been killed. Tens of thousands of mourners streamed past his bier. Yet, even in repose, Long was surrounded by armed guards, who had been instructed to keep the press from photographing the Kingfish in his coffin. The lone reporter who managed to capture a shot of Long lying in state did so at the risk of attack, and, after capturing the image, literally fled the premises. Even in death, trying to provide coverage of the Kingfish could be a dangerous assignment.

Long’s legacy was a mixed and messy one for the state, and it included the recently passed newspaper legislation that amounted to another attempt by Long to punish his opponents in the press. (Long had described the law in simple terms as “a tax on lying.”) A consortium of the state’s publishers joined together and pressed a challenge against this law, which they deemed a bald attempt to chip away at the US Constitution’s First Amendment guarantees, especially because it targeted only newspapers with a circulation of twenty thousand or more. The plaintiffs, who published the state’s thirteen largest newspapers, argued that the tax was calculated “to limit the circulation of information to which the public was entitled under” constitutional guarantees. Each of these publishers had been required under the new legislation to “file a sworn statement every three months showing the amount and gross receipts” of their business over that term. Thus the law not only targeted the state’s largest newspapers but also, through its enforcement, kept the publishers under close state surveillance, if not supervision.The year following Long’s death, the US Supreme Court made the final decision in the case. The nation’s highest court supported a lower court’s decision that enforcement of the tax would be unconstitutional. The court noted that the Louisiana law reflected earlier British laws designed to “prevent or abridge the free expression of any opinion which seemed to criticize or exhibit in an unfavorable light, however truly, the agencies and operations of the government.” In an indirect acknowledgment of the role Long had played in trying to control or punish his opponents in the press, the opinion also pointed out that “with the single exception of the Louisiana statute . . . no state during the one hundred fifty years of our national existence has undertaken to impose a tax like that now in question.” The justices further made clear that, in their view, the law not only abridged the freedom of the press but also denied the publishers equal protection under the law.

Today, the open hostilities between Senator Long and Louisiana’s newspaper publishers might seem safely historical. Yet Long’s attempts to control his own political messaging when existing press outlets failed to bend to his will are actually quite timely. The technologies employed by Long were far simpler than platforms like Twitter, but Long’s intent was much the same as President Trump’s use of that medium—to circumvent existing news sources and speak directly to the people. No politician need start their own newspaper anymore. They simply need to pick up their phone to transmit messages—true or not—to millions of followers in a matter of seconds. Social media platforms have changed the way most Americans receive news and information. But, as it becomes increasingly difficult to discern truth from fiction and news from information, it may just be that the slower processes of newspaper reporting, fact-checking, and editorial discernment may be more important than ever to keeping our democracy vibrant.

One of the maxims employed in the early days of Facebook encouraged engineers to “move quickly and break things.” Such admonitions make a certain kind of a sense in our rapidly changing digital environments. But democratic institutions are not well served by this philosophy. Our political institutions have survived for almost two and half centuries, in part because they move slowly in an attempt to keep things together, even when our disagreements push us to the breaking point. The kind of compromise required to keep a democracy functioning is made possible not just by the existence of disparate news sources, but, more importantly, by the dependability of the news they offer.

Alecia P. Long is the Paul W. and Nancy Murrill Professor of History at Louisiana State University and author of The Great Southern Babylon: Sex, Race, and Respectability in New Orleans, 1865-1920 (2004). Her current project, Crimes Against Nature: New Orleans, Sexuality, and the Search for Conspirators in the Assassination of JFK, connects Clay Shaw’s 1969 trial for conspiracy to its overlooked role in the national movement for gay civil rights.

This article is part of the “Democracy and the Informed Citizen” Initiative, administered by the Federation of State Humanities Councils. The initiative seeks to deepen the public’s knowledge and appreciation of the vital connections between democracy, the humanities, journalism, and an informed citizenry. The Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities thanks The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for their generous support of this initiative and the Pulitzer Prizes for their partnership.